Blood Moon: Lunar Eclipse Myths from Around the World

Millions of people will have the opportunity to see a lunar eclipse – an event popularly known in the media as a “blood moon” – on Friday July 27. Visible for most of the world including South Africa – only North America and Greenland are expected to miss out – it’s set to be the […]

Millions of people will have the opportunity to see a lunar eclipse – an event popularly known in the media as a “blood moon” – on Friday July 27. Visible for most of the world including South Africa – only North America and Greenland are expected to miss out – it’s set to be the longest one this century, so there is plenty of time to take a look.

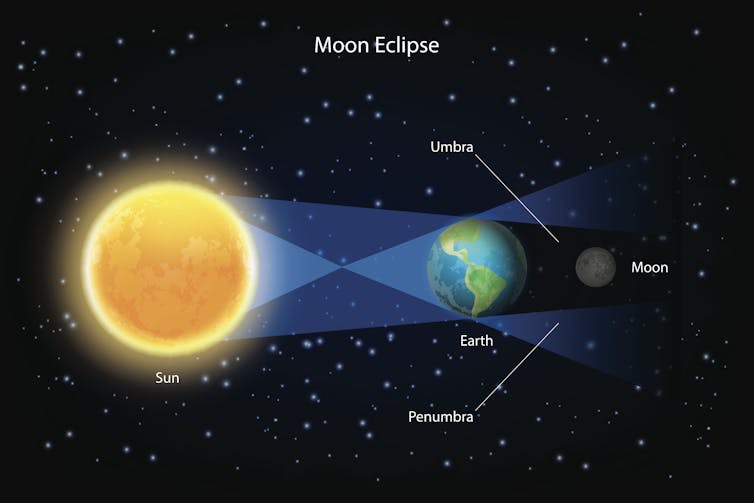

During such an eclipse, the full moon moves into the shadow of the Earth cast by the sun, and is momentarily darkened. Some sunlight still reaches the moon, refracted by the Earth’s atmosphere, however, illuminating it with an ashen to dark red glow, the colour depending on atmospheric conditions.

As a communicator of astronomy, the term “blood moon” is a major thorn in my side, since it suggests something other than a lunar eclipse and conjures images of a moon shimmering in crimson red colours, which is not at all accurate. But as a cultural astronomer, the phrase displays some of the interesting ways in which modern society creates its sky stories.

Lunar eclipses have fascinated cultures across the globe, and inspired several striking myths and legends, many of which portray the event as an omen. This is not surprising, since if anything interrupts the regular rhythms of the sun or moon it impacts strongly upon us and our lives.

Lunar malevolence

For many ancient civilisations, the “blood moon” came with evil intent. The ancient Inca people interpreted the deep red colouring as a jaguar attacking and eating the moon. They believed that the jaguar might then turn its attention to Earth, so the people would shout, shake their spears and make their dogs bark and howl, hoping to make enough noise to drive the jaguar away.

In ancient Mesopotamia, a lunar eclipse was considered a direct assault on the king. Given their ability to predict an eclipse with reasonable accuracy, they would put in place a proxy king for its duration. Someone considered to be expendable (it was not a popular job), would pose as the monarch, while the real king would go into hiding and wait for the eclipse to pass. The proxy king would then conveniently disappear, and the old king be reinstated.

Some Hindu folktales interpret lunar eclipses as the result of the demon Rahu drinking the elixir of immortality. Twin deities the sun and moon promptly decapitate Rahu, but having consumed the elixir, Rahu’s head remains immortal. Seeking revenge, Rahu’s head chases the sun and moon to devour them. If he catches them we have an eclipse – Rahu swallows the moon, which reappears out of his severed neck.

For many people in India, a lunar eclipse bears ill fortune. Food and water are covered and cleansing rituals performed. Pregnant women especially should not eat or carry out household work, in order to protect their unborn child.

A friendlier face

But not all eclipse myths are beset by such malevolence. The Native American Hupa and Luiseño tribes from California believed that the moon was wounded or ill. After the eclipse, the moon would then need healing, either by the moon’s wives or by tribesmen. The Luiseño, for example, would sing and chant healing songs towards the darkened moon.

Altogether more uplifting is the legend of the Batammaliba people in Togo and Benin in Africa. Traditionally, they view a lunar eclipse as a conflict between sun and moon – a conflict that the people must encourage them to resolve. It is therefore a time for old feuds to be laid to rest, a practice that has remained until this day.

In Islamic cultures, eclipses tend to be interpreted without superstition. In Islam, the sun and moon represent deep respect for Allah, so during an eclipse special prayers are chanted including a Salat-al-khusuf, a “prayer on a lunar eclipse”. It both asks Allah’s forgiveness, and reaffirms Allah’s greatness.

A misleading history

Returning once more to blood, Christianity has equated lunar eclipses with the wrath of God, and often associates them with the crucifixion of Jesus. It is notable that Easter is the first Sunday after the first full moon of spring, ensuring that an eclipse can never fall on Easter Sunday, a potential mark of Judgement Day.

Indeed, the term “blood moon” was popularised in 2013 following the release of the book Four Blood Moons by Christian minister John Hagee. He promotes an apocalyptic belief known as the “blood moon prophecy” highlighting a lunar sequence of four total eclipses that occurred in 2014/15. Hagee notes that all four fell on Jewish holidays, which has only happened three times before – each apparently marked by bad events.

The prophecy was dismissed by Mike Moore (General Secretary of Christian Witness to Israel) in 2014, but the term is still regularly used by the media and has become a worrying synonym for a lunar eclipse. Given the enduring superstitions, it is profoundly unhelpful for science communicators trying to remind everyone that the so-called “blood moon” is nothing to be feared. It may be impressive, and it may be the longest for a century, but it is simply an eclipse.

So, by using the term “blood moon”, we are combining superstition with science, just as the Hindu folktale of Rahu provides a legendary description of lunar orbital mechanics. The “blood moon” attracts interest in the sky and lunar eclipses, but rather than awaiting doom and destruction we can better view it along the lines of the Islamic interpretation – as a monumental illustration of the fascinating and real motions of our solar system.

So my suggestion is this: watch the lunar eclipse as how the sky unfolds above you. Give it your own name, give it your own meaning, and enjoy it with your friends and family. And I think you’ll find that the term “blood moon” cannot do justice to the wonder of what you’re watching.

Daniel Brown, Lecturer in Astronomy, Nottingham Trent University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.