Oh Pretoria, You’re Breaking my Heart

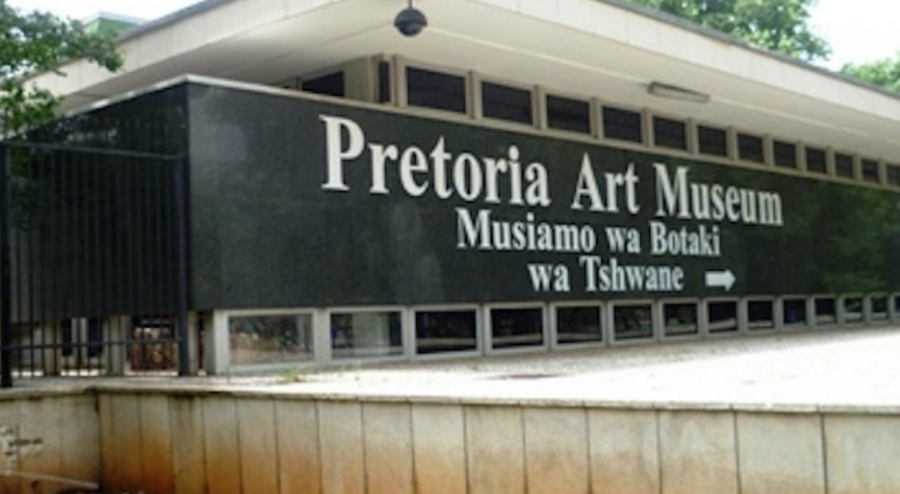

How does a municipal structure in place for decades get broken with abandon? Is it a process? What breaks first that is deemed not important enough to fix? The abysmal current state of Pretoria Art Museum is a crying shame to its proud, polished history. It feels as though the best solution is to shut […]

How does a municipal structure in place for decades get broken with abandon? Is it a process? What breaks first that is deemed not important enough to fix? The abysmal current state of Pretoria Art Museum is a crying shame to its proud, polished history. It feels as though the best solution is to shut it down and give the vagrants who dry their smalls on the Bartholomeu Dias sculpture in the museum’s park, a roof over their heads.

You drive into PAM’s parking lot – the museum campus occupies a full block of central Pretoria, including lavishly sized grounds and a generously structured building. It’s a weekday at the end of the year. People are on leave from work. Children are not at school. The parking lot has two police vans parked at random in the shade. Their occupants sit in their vehicles, doors open and legs out. It’s lunchtime. They eye you quizzically over their greasy burgers: “What are you doing here?” they seem to ask. There are no other cars.

You ignore that. Mount the stairs to the 1970s-styled venue. And look to the right. The grass is bald; freshly washed T-shirts are drying on the bronze public sculptures.

Come, come, Pretoria. It’s time to think out of that box. Or surrender it to the homeless.

The security guard sits in her belted bulging regulation trousers, fingers at her weave, phone at her ear. She clearly uses all her airtime and battery power in this job, daily. With her chin, she instructs you to sign the visitors’ book; she doesn’t deign to pause in her conversation to greet you.

You enter the space. The next security guard, behind the desk grins vacantly: R22 he asks. He doesn’t offer a receipt. And if you think of the numbingly boring life he must lead day in and day out sitting in that chair, with maybe three visitors a month you feel this arbitrary sum can be viably chalked down to charity; you let it go.

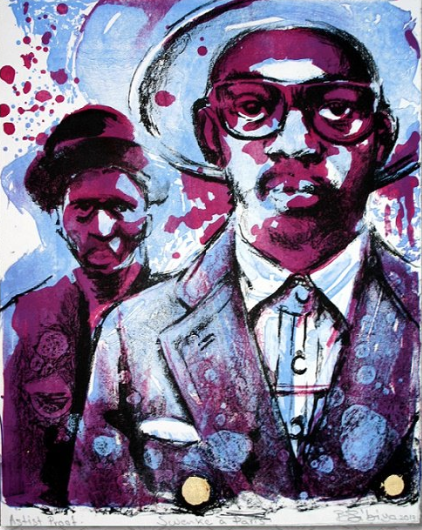

You ask where the Keith Dietrich exhibition is; the man gesticulates vaguely. “There’s art everywhere,” he frowns. “This is a gallery.” He returns to his catatonic lassitude immediately.

The first thing you encounter on your left is the museum’s curious collection of ceramic art. It’s so precious and fragile no one is allowed to see it. You’re only allowed to peer through the thick and dusty glass at how the works are irretrievably ramped against one another, frozen in time.

And there is Dietrich’s show. It’s a gem in a slum. Having had your fill of this beautiful, terrible, sophisticated reflection on society and slavery, your instinct is to flee, at once. But fatal curiosity holds you back. And oh my goodness: cheek by jowl with Dietrich’s show is a group of the most wretched little JH Pierneefs imaginable.

Exhibiting art is a complicated exercise. It’s about PR as much as it is about art history. But, it’s also about the behind-the-scenes magic that makes a theatre set design into a whole world, and a dance venue into a place of dreams: an art gallery needs proper lighting. Maybe the Pierneefs in this show are not wretched, but with stunted lighting and a devastating sense of sameness, your mind gets numbed. The works are ignominiously killed. Your sluggishness drags you forward.

There’s an exhibition by contemporary photographer Michael Meyersfeld in the next space. It features giant texts on the wall which scream out at you so loudly they destroy the work completely. You come away unable to remember what the words say or the photographs depict. It’s not clear who made these aesthetic decisions or sanctioned them. Or why.

The next space presents the work of Artists’ Proof Studio artist Bambo Sibiya. Beautiful drawings and extraordinarily fine linocuts hang in a place where clearly the lighting guy got side-tracked. It’s also a space where the low ceiling fights so obviously with the work exhibited, you can’t breathe properly.

Had enough? Probably. But the day would not be complete if you’d missed PAM’s final disappointment. This dreadfully dry potted history of South African art, from San Rock art, through the mists and mothballs of high apartheid to art produced in protest and concept, has been on show for at least a year – I brought students here last February – and everything’s still in the same dusty sequence. You come away from it with moist eyes. From lots of yawning.

It’s in the long, potentially elegant space of the Albert Werth Hall, named in honour of PAM’s first curator, who enthusiastically took up the museum’s reigns in 1963. From the 1990s, this was where the Sasol New Signatures competition happened. (Curiously this competition is still hosted at PAM, but clearly not in the Albert Werth Hall). It was here where the remarkable, fabulous work of Dutch-born artist Daphne Prevoo was showcased in 2005, an unequivocal highlight for that year, if not that decade, searing images into visitors’ minds that are still there.

The show is stripped of wow, bleached of life.

Art history is a funny discipline. While it contains the rollicking beasts in the hearts and sensibilities of talented, sensitive people on the forefront of society who saw things differently and had the courage to say so, it’s about beauty, as it’s about politics and circumstance. And it’s about fun. And horror. But an exhibition is seldom a self-generated miracle. A curator’s hand matters.

Steven Cohen’s Selfish Portrait (1999) an upholstered chair silkscreened and hand-coloured, is the gem on this side of the slum, but it isn’t exhibited in a way to make you swoon.

There’s also lovely Walter Oltmann, Cyprian Shilakoe’s represented, as is William Kentridge. But the show is stripped of wow, bleached of life.

You exit the building. All you want to do is blindly hit the highway, saving off your thirst for the first cheerful roadside fast food place. There’s nothing here to offer you solace. Or even refreshment. Drinking toilet water feels dodgy. The Spar over the road looks skanky. Besides, you haven’t stamina to walk further than your car.

While PAM reeks of apartheid thinking, it really did evolve: the collection started in 1930, in Pretoria’s town hall. PAM’s erection was completed in the 1960s. Indeed, South Africa’s prime minister HF Verwoerd – the architect of apartheid himself — laid PAM’s foundation stone. But the forward thinking in the collection from its very inception was kick-started by work bequeathed from the estate of Sir Max Michaelis (1852-1932), a mining magnate and art patron.

Michaelis’s collection, valuable though it may have been, largely comprised work by Northern Dutch masters from the 17th and 18th centuries, which was already well represented in Johannesburg and Cape Town. It did, however also include work by local masters: Pierneef, Pieter Wenning, Frans Oerder, Anton van Wouw and Irma Stern.

The city council developed PAM’s focus on local talent; the initiative developed its own momentum.

The space was enlarged in 1975 and 1988 and upgraded in 1999. But then what?

Not only does the space today have paltry visitors, creative energy or attention to curatorial detail, not to mention no sense of the sacredness that would make the very idea of hanging freshly washed broeks on the side of a sculpture anathema to even a vagrant, but it also has no Internet presence.

It’s unforgivable. Yes, times are tough; money’s too tight to mention and arts funding is always in business’s cross-hairs. But by the same token, this creative industry is replete with talented, brave, passionate people who understand how earning money and doing things that matter must balance. Come, come, Pretoria. It’s time to think out of that box. Or surrender it to the homeless.

Robyn Sassen is a freelance arts writer, based in Johannesburg. She is the former Arts Editor of the SA Jewish Report and enjoys a specialty in writing critically about visual art, theatre, contemporary dance and books. This article was first published on Robyn’s blog My View The Arts at Large, and can be viewed here.