What SAA and the Government Could Learn from Ethiopian Airlines

South African Airways is in dire straits. According to an internal memorandum of 6 November 2015 made public by the media last month, SAA is technically insolvent and thus guilty of reckless trading. It is therefore legally obliged under the Companies Act to file for either liquidation or business rescue. On 24 December, Citigroup withdrew […]

South African Airways is in dire straits. According to an internal memorandum of 6 November 2015 made public by the media last month, SAA is technically insolvent and thus guilty of reckless trading.

It is therefore legally obliged under the Companies Act to file for either liquidation or business rescue. On 24 December, Citigroup withdrew a R 250 million financing facility, leaving SAA without cash – a situation which has prompted National Treasury intervention.

Many point toward the fact that SAA is a state-owned enterprise (SOE) as the basis for such a spectacular failure. Such reasoning is entirely understandable in a South African context. Indeed, the government seems astonishingly effective at undermining the efficacy of its parastatals. Whole areas of our major cities go without electricity for hours at a time; the postal service is neither trusted nor competent enough to deliver the post; and buying water in a shop is sometimes more reliable than turning on a tap. It’s difficult to deny the existence of a common denominator.

But such reasoning is also incorrect. SAA’s failure is a result of the objectives and quality of management; not state ownership.

Ethiopian Airlines is currently the fastest-growing, most profitable and largest African airline. Since 2005, the airline has grown at an average rate of between 20 and 25 percent per annum. Its profits for the 2014/15 fiscal year amounted to $175 million, more than all other African airlines combined.

MOST NETWORKED CARRIER, AND GROWING

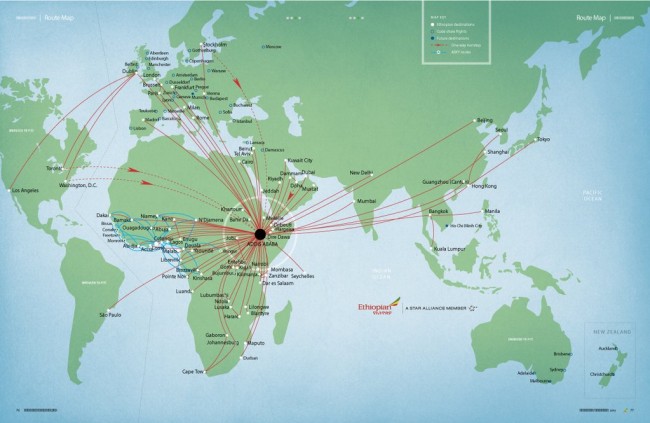

Moreover, EA is now the most networked African carrier, both in terms of scheduled routes within the continent itself as well as in terms of international connectivity. It serves 91 international destinations. Fifty-two of these are in Africa, 15 in Europe and the Americas, and 24 spread across Asia – from the Gulf to Tokyo. The fleet is the largest and youngest in Africa: 68 sophisticated passenger planes with an average age of five years make over 230 daily departures.

The airline also dominates freight and cargo within Africa. Plans were recently announced to build a 1.2 million tonne annual capacity cargo terminal at the airline’s hub in Addis Ababa. This is just slightly smaller than that of London Heathrow, Europe’s fourth largest, and speaks of the ambition of the airline. It currently covers 48 cargo routes with eight dedicated aircraft. By 2025, it aims to have increased the cargo fleet to 18.

One major factor underlying EA’s success – or its strategic capture of the African market at least – is the establishment of a ‘multi-hub system’ on the continent.

“Africa is a huge continent” Henok Teferra Shawl, vice president for Strategy and Alliances at EA, commented, “so one hub serving the continent from Addis Ababa we felt was not enough.”

Thus it bought the failing ASKY Airlines in Togo and Air Malawi. This allowed it to set up secondary feeder hubs that now serve Western Africa and Southern Africa respectively before channelling passengers in significantly greater numbers to Addis Ababa for global distribution. There are also reportedly plans for a Central African hub, potentially in the Democratic Republic of Congo. This is said to be aimed at catering for the growing demand in China for efficient connectivity to the resource-rich, oil-producing nations making up the Central African Economic and Monetary Community.

Positioning itself as the leading hub for Africa/Asia connectivity makes sense, given Ethiopia’s location – a stroke of good fortune. But challenging the established dominance of the fabulously wealthy and perhaps even better situated Gulf carriers was, and remains, no easy feat.

By pursuing alliances with established Asian airlines, such as Singapore Airlines and the largest Japanese carrier ANA, EA has been able to rapidly expand into Asia. Significantly, for example, it now boasts 28 direct flights to and from China a week. Cooperation between airlines is a relatively new and growing global trend, and EA has demonstrated vision and sensitivity by engaging with it.

Profitability is rarely coincidental; market dominance even less so. Rather, the success of any enterprise comes as a consequence of a clear, considered and profit-orientated strategic business model underpinned by professionalism, industry experience and commercial astuteness. EA fits the bill.

Yet despite all this, EA has been state-owned ever since its creation in the 1940s at the behest of Emperor Haile Sellasie. Moreover, government oversight is retained in much the same way as SAA through political appointments to the board of directors. The current chairman is the deputy prime minister, and several other board members are leading government figures; including the minister of transport and the minister of mines. It seems not unfair to posit that the remaining members are politically connected to some extent. So, on the story often told about SAA, how can this be reconciled with EA’s success?

LESS CRONYISM, MORE AUTONOMY

Firstly, the Ethiopian government, in their capacity as owners, and the board of directors, in their capacity as representatives of the owners, prioritised hiring professional management staff on merit rather than political placements motivated by patronage and cronyism.

The current management team has over 421 years of airline industry experience between them. The CEO, Tewolde Gebremariam, began working for EA in 1985 in the cargo traffic handling department. He worked his way up the ladder gradually, gaining experience, until finally reaching the position of CEO. He has since won multiple awards, including African CEO of the Year 2012 from the African CEO Forum and The Best Africa Business Leader from the Washington, D.C-based Corporate Council on Africa.

Secondly, the Ethiopian government, as owners, and the board, as their representatives, then allowed the management team, in their capacity as the professionals, to run the company on sound business principles. Shawl stated in an interview that “they [the government and board] know that this is a company and it has to be operated on commercial considerations”.

Thus the diligent, experienced and reliable management team are trusted by the shareholder and given the autonomy to act without concern for political interference or fear of political reprisal. At the same time, and like any business, they are also made aware of their accountability – which is judged purely on performance, not partisan objectives.

For example, Ethiopian civil servants do not receive free tickets. Quite a contrast to here in South Africa, where civil servants continue to receive a quota of free flights for themselves and family even after leaving public office. Further, EA employs the industry average number of staff needed on board each flight – whereas SAA employs twice that number.

All this reflects the fact that EA, in contrast to SAA, is not considered an opportunity for patronage, rent seeking and clientelism. Though state-owned, it is, first and foremost, a business. And because it is managed like this, it is able to raise its own debt, finance its own development, expand, grow and turn a profit – all without recourse to public subsidies. In fact, it currently pays dividends to the government. It is exactly how a state-owned enterprise can, and should, be run.

The lessons for SAA’s shareholder, our government, are manifold and yet straightforward and easy to implement. An entirely new board should be appointed with a mandate to operate along business lines, using EA as a model. The senior management team should be strengthened by the appointment of people with industry experience who can develop the strategic vision to take the airline forward as a business. Then allow the managers the freedom to do their jobs. It’s that simple.

Andrew Barlow is a researcher at the Helen Suzman Foundation, which has kindly allowed us to republish his article. The original article can be seen here.