How Investors See South Africa: Lots of Potential, Not Worth the Hassle

South Africa has narrowly survived a downgrade of the rating of its government bonds. The reprieve, however, is temporary because government has been warned by the Big Three rating agencies – Fitch, Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s – to pull up its socks. South Africa’s current rating – just about investment grade, heading south fast […]

South Africa has narrowly survived a downgrade of the rating of its government bonds. The reprieve, however, is temporary because government has been warned by the Big Three rating agencies – Fitch, Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s – to pull up its socks.

South Africa’s current rating – just about investment grade, heading south fast – puts it more or less on par with countries such as Italy and Spain. And even with a downward trajectory through speculative grade it is still several notches away from outright “junk” or “CCC”.

But a downgrade to sub-investment grade would slow inward investment and the economic fallout could become a self-fulfilling prophecy: as outflows increase, the economy slows.

Such meta-narratives are especially powerful during periods of global turbulence as is currently being experienced, with volatile commodity prices, the oil rout, the slowdown in China and speculative investors moving large amounts of short-term capital very quickly around the world.

Why Sovereign Debt Matters

When governments need to raise money they may decide to do so by borrowing on international financial markets. Such loans, or sovereign bonds, are each assigned a rating by a credit ratings agency. The rating estimates the likelihood of a government’s creditors being repaid against a range of factors. These include hard economic data, political analysis, reputation and sentiment.

The yield of the bond can be roughly understood as the interest rate on a loan. The lower the credit rating, the higher the risk of a default and the higher the yield payable to investors for taking on that risk.

It’s important to note that sovereign bonds are just another asset class investors can consider in a universe of investable assets. A downgrade is not desirable as it may slow down institutional investment and make the economy more vulnerable to speculative activity. But some investors may very well have an appetite for risky sovereign debt if it means they can make a lot of money.

In fact, high-end brokerages such as Charles Schwab advise investors on investing in high-yield, sub-investment grade emerging market debt. This sort of speculative sentiment is exactly what drove the “Africa Rising” narrative. It also drove the introduction of ratings for previously unrated sub-Saharan sovereigns, as investors sought new sources of alpha in the low-growth fallout of the financial crisis in Europe.

Despite this, countries need to borrow to plug the gap between projected tax revenue and budgeted expenditure. However, as debt has to be repaid at some point in the future, any debt raised should be used to finance investment such as infrastructure, which expands an economy’s capacity and therefore potential for growth and increased tax revenue. In addition, the interest government pays on its debt is of paramount importance.

What There’s to Like/Not Like About South Africa

Rating agencies have cited maintaining investor confidence as one of the critical factors towards preventing a future downgrade for South Africa. So it’s important to know what investors were thinking about South Africa in the run up to the ratings, and what they’re thinking now.

The first point to make is that local institutional investors and financial institutions are also influenced by the global context. The political and economic developments of all countries are viewed proportionately to other markets. For example, in the case of South Africa, Investec Asset Management evaluates the country relative to other emerging markets. It recently did so in relation to Brazil in particular.

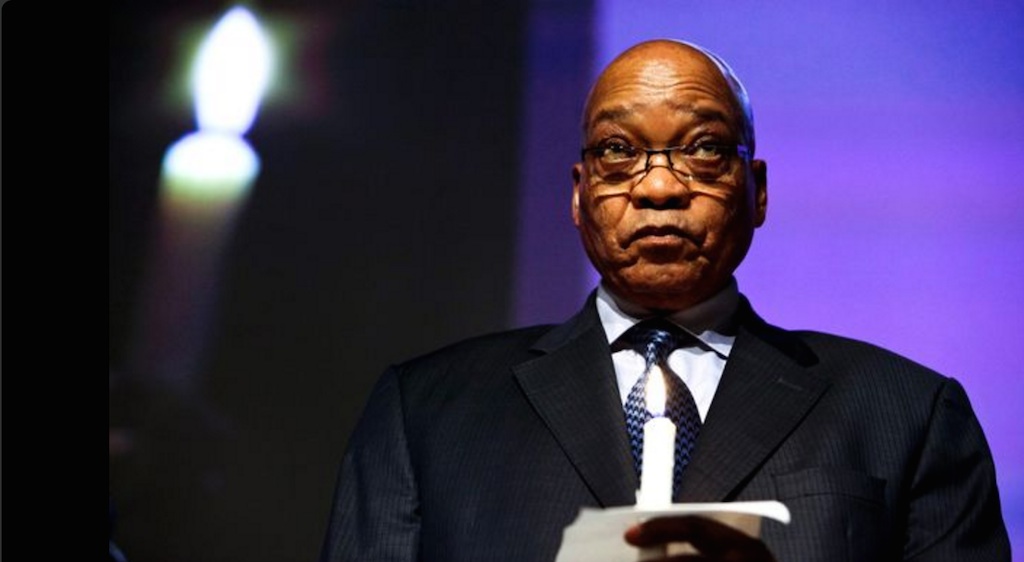

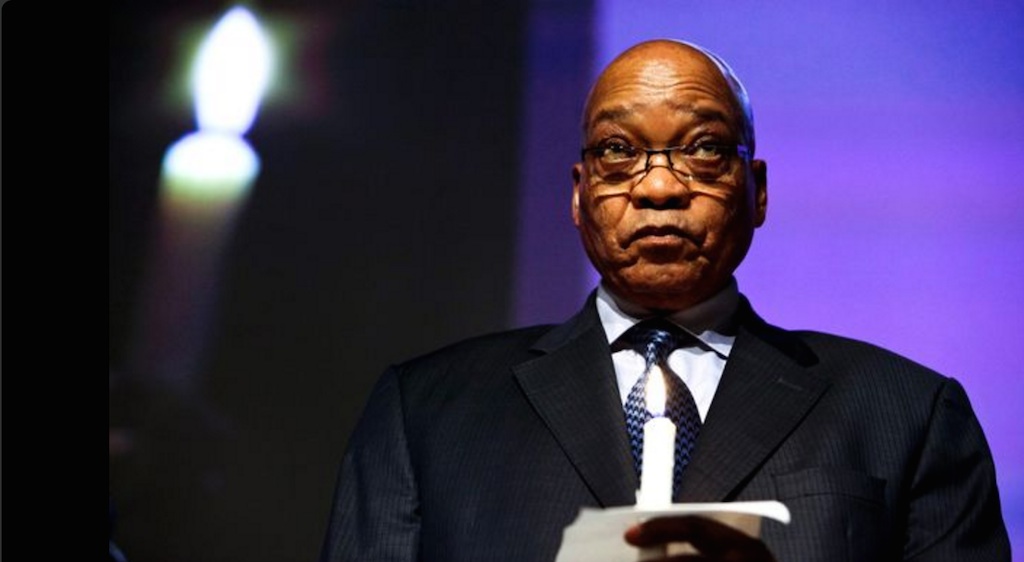

Investec’s house view on the two countries is informed by two insights. The first is that South Africa and Brazil have political headwinds that are governance risks to long-term economic development, and may present watershed moments. The other is that the strength of institutions in these countries is often overlooked. An example of this is the South African Constitutional Court’s ruling on President Jacob Zuma’s spending on his private home in Nkandla.

Publicly available international perceptions also matter. An example is the World Economic Forum competitiveness ranking. South Africa is ranked 49th out of 140 countries and only second to China among the Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa group.

Investors also like the country’s sound fundamentals. These include a sophisticated financial markets sector, and respect for property rights and the rule of law. And despite US government complaints about infrastructure gaps and the inaccessibility of officials, it still regards South Africa as an important gateway to the rest of the continent.

However, inequality, unemployment, power shortages, policy incoherence around black economic empowerment and labour relations remain risk factors. The UK government, for example, singles out corruption, fronting around empowerment deals and dubious tender processes.

International investors are also still rattled about President Zuma’s unexpected decision late last year to replace his respected finance minister, only to reverse the decision a few days later.

Another bugbear is Zuma’s weakened position and how succession within the ruling African National Congress will play out, particularly the realisation that Cyril Ramaphosa, currently the deputy, may not have enough power to become president.

The competition between Zuma and Finance Minister Pravin Gordhan is also being watched closely, as Gordhan is seen as a business champion.

Overall South Africa, right now, is viewed as a terribly difficult place to do business, with overweening bureaucracy, a collapsing education system, poor policy and militant labour groups. Kenya and Nigeria are increasingly seen as more favourable destinations.

As one investment advisor in London pithily described South Africa:

Lots of potential, not worth the hassle.

South Africa is thus particularly vulnerable with its relatively liquid portfolio flows and sophisticated financial markets. In addition, the rand, with its high interest rate, is a particular favourite commodity currency for speculators in the carry trade. And indeed, both Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s have worried aloud about the combination of low growth, high debt and political risk in the current global environment.

But some healthy scepticism and perspective is also in order. Yes, South Africa’s parliament is out of order, but there have been fisticuffs in South Korea too.

And there is no such thing as “idiosyncratic emerging market risk” – a patently hypocritical concept. South Africa has had its recent share of protests, but the 2011 London riots were intense, with three days of violence during which 450 arrests were made. Nor are emerging markets essentially “corrupt”. Take Italy, for example. And rent-seeking patronage networks and what the Chinese call guanxi – networks of influence – are a feature of politics everywhere.

Economic Policy Priorities

The sooner South Africans realise they have frittered away the Mandela dividend in a cutthroat global economy, the better. But this realisation does not have to come at the expense of equal negotiating power in trade and investment. By growing the economy inclusively with a focus on human development, the business environment also becomes more sustainable. Investors know this too.

Economic policy requires a shift away from the short-termism of a gross domestic product evangelism that is subject to the vagaries of hot money in a panicked and turbulent global economy. If this continues to be the case, economic development will only ever elicit a Pavlovian response from rating action to rating action.

Desné Masie is a visiting researcher in international political economy at the University of the Witwatersrand. This article was originally published in The Conversation. Read the original article.