Update from the Karoo: What the Frack is Going On?

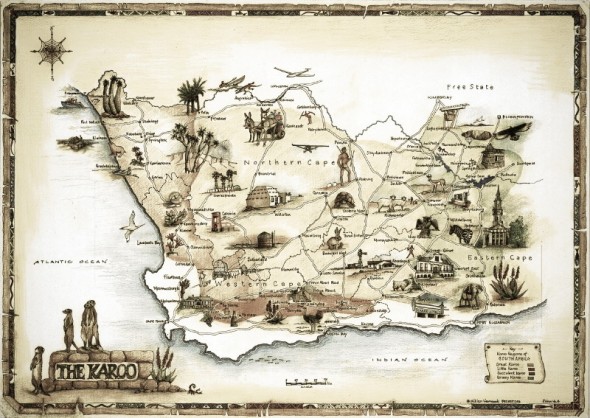

The Karoo lies at the heart of South Africa in many ways. Its spirit of place lies in silence, open horizons, flat-topped hills, windpumps, sheep and starry nights. But this peaceful silence continues to be threatened by the possible implementation of fracking. South African President Jacob Zuma announced during his State of the Nation address […]

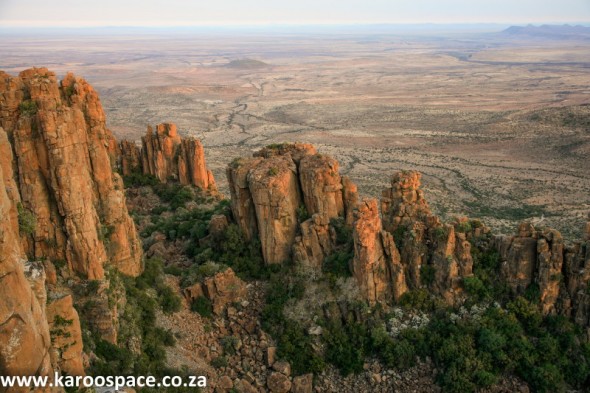

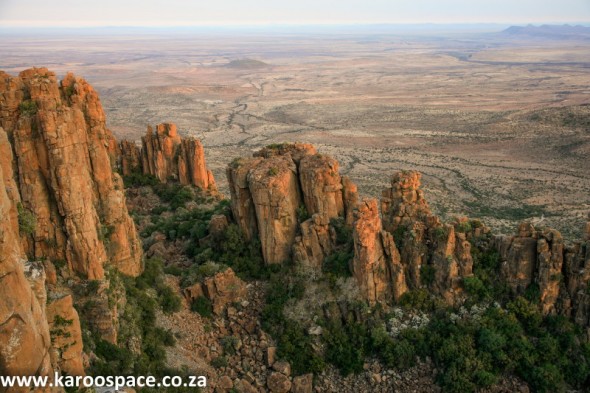

The Karoo lies at the heart of South Africa in many ways. Its spirit of place lies in silence, open horizons, flat-topped hills, windpumps, sheep and starry nights.

But this peaceful silence continues to be threatened by the possible implementation of fracking. South African President Jacob Zuma announced during his State of the Nation address on 13 February 2014 that “the development of petroleum, especially shale gas will be a game-changer for the Karoo region and the South African economy.”

The President said that “having evaluated the risks and opportunities, the final regulations will be released soon and will be followed by the processing and granting of licenses.”

But it is not that simple. Fracking in the Karoo is not a fait accompli and passionate anti-fracking supporters have not given up hope.

Let’s start at the beginning…

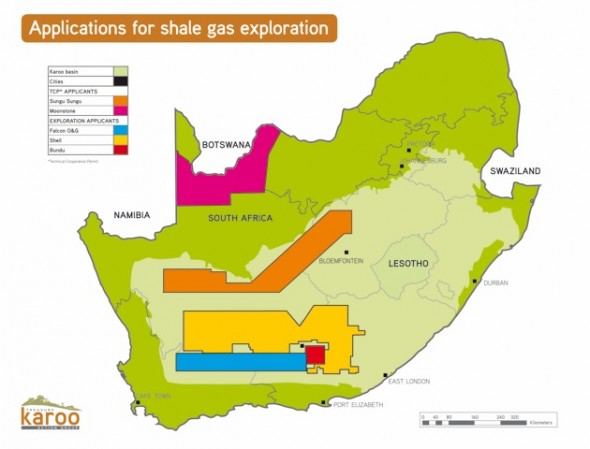

The others are still busy with desktop studies and have not yet been given permission to apply for exploration licences. These are Sungu Sungu (orange) and Moonstone (pink)

For South Africans who know and love the Karoo, it came as a profound shock when Royal Dutch Shell took out a two page advertisement in the Sunday Times in January 2011, showing the Government had granted it concessions to explore for shale gas using a highly controversial technique called hydraulic fracturing over 90 000 square kilometres.

A company called Falcon Oil and Gas laid claim to 30 000 square kilometres in an area which included the Aberdeen, Jansenville and Merweville districts (They later went into partnership with Chevron.) Bundu (which later went into partnership with Challenger Energy of Australia) claimed 3 200 square kilometres between Graaff-Reinet and Pearston.

Hydraulic fracturing (fracking) is a technique of releasing gas held in tight rocks deep underground, using millions of litres of water, plus chemicals and sand. It was pioneered in America in the 1990s, but expanded rapidly only after 2005.

Opposition rose swiftly and dramatically, centred mostly around water. How could this massively water-intensive industrial process that cracked open rocks underground be used in a semi-desert where more than 80% of all towns and thousands of farms depend on groundwater?

Since 2011, the anti-fracking fight in defence of the Karoo has become one of the most interesting environmental battles ever fought in South Africa.

Jonathan Deal, the author of a book called Timeless Karoo, started up a Facebook page in opposition to this shale gas exploration and possible hydraulic fracturing (fracking), called “Chase Shell Oil out of the Karoo” (now with 9 700 members).

“It probably wasn’t the sexiest or the best name, but it was all I could think of at the time,” shrugged Deal. “It took off so fast that within days it was too late to change the name.”

This social media initiative later spun off a real Non-Governmental Organisation, called Treasure the Karoo Action Group, headed by Deal.

There were demonstrations all over the Karoo and some cities, notably Cape Town. The oil and gas companies and Government were taken aback by the fierce, rapid opposition.

There was nothing in the South African lawbooks that controlled an industry like fracking. It was also the first time in South Africa that such vast areas had been conceded for mineral exploration.

A Critical Review, coordinated by TKAG and with contributions from some of the best scientific and legal minds in the country was submitted to Parliament in April 2011. It highlighted the potential impact of shale gas exploration and exploitation in the Karoo, as well as pointing out shortcomings in the current legal system.

Government then declared a moratorium on shale gas exploration in the same month. The moratorium remained in place September 2012.

No one harboured any illusions that the moratorium would turn into a ban. The US Energy Information Agency estimated at the time that South Africa’s shale gas reserves stood at 485 trillion cubic feet (tcf), ranking it fifth in the world. This made exploitation a tempting prospect for the South African government – specifically as a fuel to create energy via gas-fired power stations. The possibility of using shale gas to alleviate the country’s energy crisis and simultaneously create jobs sounded irresistible.

Shell in particular lobbied government officials on all levels, from local municipal managers to energy ministers, emphasising what a wonderful windfall this was. (It recently emerged this talking up of shale potential may have backfired on them – see below.)

Shell embarked on a communications exercise around the Karoo, seeking what they called “a shared understanding around shale gas”. At the slightest indication of interest they would book flights and hire cars, travelling deep into the hinterland to address anyone who cared to listen. Church groups, a handful of farmers, guesthouse staff, book clubs and businessmen all got a chance to speak to Shell South Africa’s Upstream general manager Jan-Willem Eggink and his staff. They gave Powerpoint presentations boasting that shale gas was “abundant, affordable and acceptable”.

By contrast, Falcon and Bundu were completely invisible.

Meanwhile, the anti-fracking opposition was having none of it. Support broadened and a startling variety of organisations spanning deep green to social and environmental rights came out against fracking. These included WWF-SA, the Endangered Wildlife Trust, Afriforum, Wilderness Foundation, Earthlife Africa, groundwork, religious groups like the Southern African Faith Communities’ Environment Institute (SAFCEI) and the Verenigde Gereformeerde Kerk, farmworkers and emerging farmers’ representatives like Southern Cape Land Committee. Khoi and San leaders stood up against the prospect of fracking.

In June 2013, however, the first signs came that the Karoo’s distinctive geology and dolerite outcrops might be an even more powerful deciding factor. The EIA downgraded South Africa’s shale potential to 390tcf, mentioning ‘igneous intrusions’ in the Karoo Basin as one of the reasons.

This refers to the molten rock rose up into the Karoo Basin 183 million years ago (the reason we have flat-topped mountains today), it may have contributed to an ‘explosive degassing’ of the Karoo, as one geologist put it.

In February 2014, the Petroleum Agency of South Africa – which administers the new oil and gas industry in South Africa – dramatically dropped its ‘best estimate’ of shale gas in the Karoo Basin to only 40tcf. PASA principal geologist John Decker had previously mentioned an even lower estimate of 30tcf.

Some geologists like Dr Chris Hartnady said that even 20tcf would be a stretch.

All this speculation, though, is just that – guesswork. Not a single shale gas drill-bit has been lowered onto Karoo soil yet. This will not even happen once shale gas exploration licences are issued (something that is thought to be imminent). Lawyers have said the submissions by the gas companies are fatally flawed and will be challenged in court. And then the Environmental Impact Assessments must be done for each exploratory well, something that could take 18 months to two years.

Meanwhile, baseline testing for water quality in the Karoo is starting.

But James Lorimer, the Democratic Alliance’s shadow minister for mineral resources, recently voiced grave misgivings about whether exploration would happen at all. This comes after discussions in Parliament in the first week of March 2014, where amendments are being made to the outdated Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act.

When the African National Congress pushed through an amendment that entitled Government to a 20% free carried interest in all exploration and exploitation of oil and gas in the country, plus the right to buy out the remaining 80%, the oil and gas company people left in “a sullen mood” according to Business Day journalist Paul Vecchiato.

Afterwards, Lorimer wrote that this move showed “a depth of economic illiteracy that is hard to fathom”. He also said it was “likely to end any prospect of oil companies spending on exploring what is thought to be major oil and gas reserves off South Africa’s coast. It may well make drilling for shale gas uneconomic.”

In the second week of March 2014, the ANC used its majority to pass the contentious amendment through the National Assembly. All that remains now is for it to be accepted by the National Council of Provinces, after which it could be signed into law by President Zuma.

Analysts have called the amendment ‘catastrophic’ as it is likely to scare off would-be drillers.

But it would be good news for those who love the Karoo, just as it is…with silence, sheep and starry nights.

Pictures by Chris Marais

More Reading:

http://karoospace.co.za

www.treasurethekaroo.co.za

https://www.facebook.com/groups/chaseshelloutofthekaroo/708791695811064

http://mg.co.za/article/2014-03-12-government-pushes-through-contentious-changes-to-mineral-laws/