‘The Conscience of White SA’: Celebrating The Black Sash, 60 Years Later

Six months after Jean Sinclair, Ruth Folley, Elizabeth McLaren, Tertia Pybus, Jean Bosazza and Helen Newton-Thompson launched the Women’s Defence of the Constitution League over tea on 19 May 1955, the organisation held a conference in Port Elizabeth. The minutes of that meeting provide some insight into the tactics the women used to highlight “undemocratic” […]

Six months after Jean Sinclair, Ruth Folley, Elizabeth McLaren, Tertia Pybus, Jean Bosazza and Helen Newton-Thompson launched the Women’s Defence of the Constitution League over tea on 19 May 1955, the organisation held a conference in Port Elizabeth.

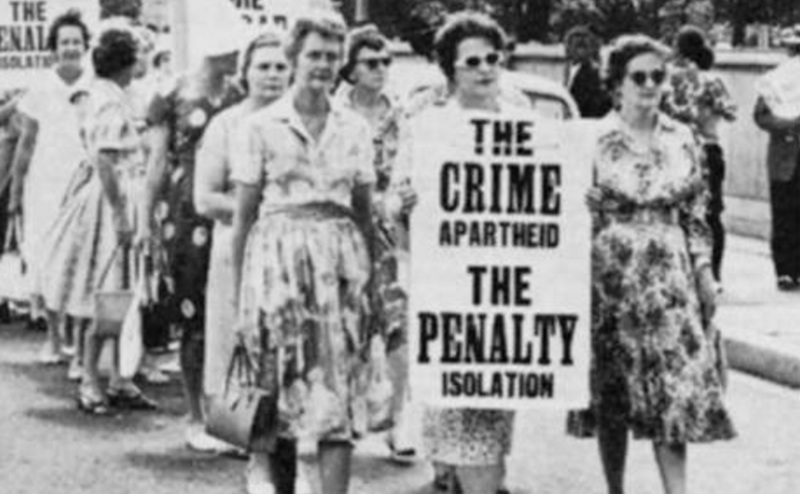

The minutes of that meeting provide some insight into the tactics the women used to highlight “undemocratic” practices by the government of the day. Strategies employed by this “silent sisterhood” included “blacksashing” – or the wearing of a black sash during silent protest vigils – as well as “haunting”.

“Ministers must be looked at,” read the minutes referring to the silent protests the women would hold from the public gallery in Parliament.

The withering stares of the women no doubt served to unsettle ministers in the ruling National Party regime, who detested this group of apparently well dressed, genteel and mostly English-speaking white women who used their position to challenge them.

Their protests immediately attracted international attention and in September 1955 Time Magazine began a feature thus: “Everywhere South Africa’s Prime Minister Johannes Strydom looked, there seemed to be women – white women in black sashes, silent and contemptuous, heads bowed in symbolic ‘mourning for the constitution’. Whenever he passed, they lifted their heads and stared.”

The Women’s Defence of the Constitution League – born out of resistance to a Parliamentary Bill designed to increase the number of National Party representatives in the Senate in order to pass the Separate Representation of Voters Bill and which would disenfranchise coloured citizens – soon changed its name to the Black Sash, reflecting the trademark sash the women wore or draped over a symbolic replica of the then-1910 Constitution.

If the Black Sash had had access to Twitter back then, #blacksashing #vigil and #sitin would have trended regularly as the women relentlessly campaigned and mobilised, first against the legal amendment – a battle they lost – and then later against almost every other violation of human rights by the Apartheid state including racial segregation, migrant labour, influx control, detention without trial, state censorship and the various states of emergency the government imposed on the country.

In the 1980s the various advice offices the Black Sash ran across the country and staffed by volunteers became crucial points of resistance for the black majority in terms of challenging Apartheid legislation, mass arrests, access to information and sometimes simply to enable the provision of food and other emergencies. The advice offices offered free services also with regard to issues of employment, housing, pensions and access to health.

The Black Sash were also an invaluable source of information for newspapers operating in difficult circumstances with constant harassment by the state, bringing vital news to the attention of journalists.

The late 1950s provided a renewed hope in the resistance to Apartheid with the launch of the Freedom Charter in Kliptown in 1955 as well as the anti-pass law march on the Union Buildings by thousands of women affiliated to the Federation of South African Women in August 1956. The Black Sash subsequently set up a “bail fund” for the countless black women who were arrested and incarcerated for defying the country’s pass laws.

The Sash kept up pressure throughout the increasingly violent 1960s campaigning against the government’s plans to set up “homelands” and forcibly remove black South Africans to these areas and also staged campaigns, sit-ins and vigils after the Sharpeville Massacre in 1960.

In 1963, while the Sash opened membership to all South African women, it remained a space where white women were able to find some means of showing solidarity with the black majority as well as offering practical and visible assistance.

As the state clamped down more violently during the 1970s and 1980s, banning and imprisoning political dissidents, the women of the Sash continued to offer support or to use their position as mostly privileged white women to highlight events locally and internationally.

“Day after day, the women of the Black Sash stood in silent protest with their placards. Day after day, they continued to help those who queued outside the Black Sash advice offices. They sat in the courts; they witnessed the demolition of people’s homes and the forced removals of entire communities. Their physical, witnessing presence enabled the Black Sash to speak with authority of what its members had experienced – in the courts and at Commissions of inquiry; monitoring at sites of forced removals, potential violence or police action. Every comment, every statistic, every statement issued by the Black Sash during these difficult years was underpinned and supported by these daily experiences – in the advice offices, in fieldwork and in personal witness. This strong foundation of first-hand knowledge earned the respect of many who came to rely on this information,” reads this history of the organisation on its website.

After his release Nelson Mandela described the women of the Black Sash as “the conscience of white South Africa during the Apartheid era”, praise well earned by the ordinary women who formed part of this remarkable organisation.

After 1994 the Sash continued its work, helping to develop the Constitution, embarking on a massive voter education campaign and then later participated in plans for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

Today the Black Sash exists as a non-governmental organisation that employs professionals. It currently focuses on education, training, rights-based information, advocacy and community monitoring.

The Black Sash was, in many ways, the precursor of many of the country’s vibrant civil society organisations that exist today. The women of the Sash left an indelible legacy of resistance, which has been celebrated and acknowledged, and which hopefully still serves as inspiration and proof that the middle classes and can exert extraordinary leverage in relation to actively highlighting injustice. While many of the women of the Black Sash were privileged and married to “high-powered” men, they chose to move out of their comfort zones and to follow their consciences, sometimes at great cost.

Two books celebrating the history of the Sash will be launched at a special anniversary event to take place in Cape Town on Tuesday 19 May. The first is Standing on Street Corners: a History of the Natal Midlands Region of the Black Sash, “a labour of love” by Mary Kleinenberg and Christopher Merritt and published by The Natal Society Foundation.

The second is a biography by Annemarie Hendrikz of Sheena Duncan, daughter of Sash founder, Jean Sinclair, and who led the organisation for two terms from 1976. Duncan joined the Sash in 1963 and was one of many of the organisation’s inspiring stalwarts. Both books will be launched at an event that will take place at 6 Spin Street.

In a contemporary political landscape where our past is in danger of being re-written, it is vital that the history of the white women of the Sash is revisited. While the vast majority of white South Africans supported and benefited from Apartheid, the bravery of those white South African women who found ways to expose and oppose it deserves to be acknowledged, honoured and celebrated.

This article first appeared in the Daily Maverick and has been republished with kind permission. The original version can be read here.