Tina Turner: the singer’s resilience and defiance were typical of a survivor of intimate partner abuse

There was something elemental about the ferocity of Tina Turner’s stage strut and the grit in her voice. Her death last week, aged 83, was met with an outpouring of tributes celebrating her musical prowess. But as we mourn her passing, it’s worth noting that Tina was also a model survivor of intimate partner violence. […]

There was something elemental about the ferocity of Tina Turner’s stage strut and the grit in her voice. Her death last week, aged 83, was met with an outpouring of tributes celebrating her musical prowess. But as we mourn her passing, it’s worth noting that Tina was also a model survivor of intimate partner violence.

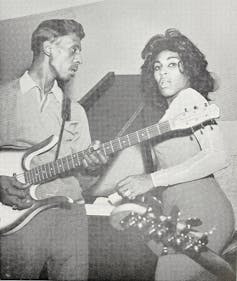

In 1981, following her split from her husband Ike Turner, Tina Turner began to speak openly about the years of abuse she had endured during their marriage. No charges related to domestic abuse were ever brought, and Ike Turner denied the accusations. Yet, over the decades Turner told a story familiar and inspiring to many other survivors.

Turner is rightly held up as a trailblazer for speaking publicly about her experience of intimate partner violence. But media coverage of Ike and Tina’s relationship has often solely focused on Ike’s physical violence.

Physical violence sells newspapers. It’s easy for observers to understand and widely considered the worst form of abuse by those who have never experienced it. When Turner first spoke publicly about her experience in the early 1980s, “domestic violence” was thought of as episodic physical assault, perhaps triggered by stress or even by the victim themselves.

However, Turner’s accounts of her relationship revealed a pattern of coercive control. This understanding of abuse is something the world is still trying to catch up with.

Not only was Ike physically and sexually violent, but he ensnared Turner in a web of other controlling tactics, including financial control, emotional manipulation, control of her identity and a pattern of charm and “love-bombing”.

It is this web of domination over victims that disempowers them and often prevents them from leaving a violent relationship. Many survivors report the emotional and psychological strategies of abuse as the longest lasting and most damaging elements of an abusive relationship. For experts in the field of intimate partner violence, Ike’s behaviour is textbook coercive control.

What makes Turner’s escape inspiring is the many layers of threat she faced and resisted beyond physical violence.

A strong (and vulnerable) black woman

Much of the media coverage of Turner’s victim-survivor status overlooks the fact that as a black woman she walked a fine line in speaking publicly about her experiences.

Research has repeatedly found that intersectional issues are faced by black women who speak out and seek support for abuse. Intersectionality describes multiple challenges or disadvantages faced by an individual with overlapping social identities, such as being a black woman. Stereotypes are one example.

In criminological theory, the stereotypical “ideal victim” is perceived as weak and submissive. This stereotype has been attached to the notion of the “battered woman” even though it does not match most survivor experiences of resistance.

Tina Turner speaking about the abuse she experienced:

There remains a widespread lack of understanding of abuse survivors as resourceful and resilient – as opposed to weak. The stereotype of the “strong black woman”, who is fiercely loving, feisty and independent is even more at odds with the “battered woman” trope. Many black female survivors are criminalised as a result of this dissonance.

The black male identity is likewise affected by deeply embedded stereotypes. Most survivors, including Turner, offer loyalty as a reason for keeping abuse private, fearing social repercussions if their partner is labelled as an abuser.

Speaking out publicly as a black woman was complex for Turner, and as other black women have expressed, her bravery and steadfastness has inspired many others to follow suit.

More than a survivor

As media coverage over recent days has pointed out, Turner refused to be defined by her experiences. In this regard, she is typical of a survivor of abuse, not an exception.

Stereotypes of abuse victims as weak and submissive often lead to popular coverage which assumes that victimhood dominates a survivor’s social identity. In my research, however, survivors often tell me that they “refused to be a victim”. What they mean as they discuss their circumstances is that they are so much more than the stereotypical “victim” of domestic abuse.

Turner was the epitome of the victim-survivor, breaking free and living her life to the full. Not all victims are privileged to have the resources to live a rockstar lifestyle. On the contrary, many are left financially destitute and often have their reputation dismantled, but all are far more than “victims”.

In the month before she died, Turner was asked how she wanted to be remembered. For all the inspiration and the enormous influence she had as a survivor of intimate partner abuse, she wanted to be remembered for the person she was and the work she did – as the queen of rock and roll.![]()

Sarah Tatton, PhD Candidate and Associate Lecturer in Criminology, Sheffield Hallam University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.