South Africa’s police are losing the war on crime – here’s how they need to rethink their approach

Government departments, civil society groups and the private sector should pool resources and work together in a co-ordinated manner to prevent violent crime.

South Africa’s crime statistics for the third quarter of 2023 show that people continue to face a serious problem of violent crime, especially murder and attempted murder. The country’s per capita murder rate for 2022/23 was the highest in 20 years at 45 per 100,000 (a 50% increase compared to 2012/13).

In response to this crisis, the South African Police Service has reconfigured its policing strategies and plans. Yet, these approaches offer very little innovation. They mostly reaffirm the way the police have typically pursued policing for the past three decades – fighting a “war” on crime and “sweeping away” criminals.

In my view, the police have adopted unsuitable crime-fighting strategies. This is a “war” the police can’t win on their own because violent crime is a complex phenomenon. It requires whole-of-government and whole-of-society approaches. Government departments, civil society groups and the private sector should pool resources and work together in a co-ordinated manner. They must be guided by a common plan. Otherwise, crime prevention efforts will be piecemeal, lacking effectiveness.

Determinants and complexity of violent crime

The scholarly literature on violent crime in South Africa, including my research, indicates that interpersonal violence is typically the outcome of a combination of risk factors over time.

One of them is the idea that violence is a legitimate means to resolve conflict between people.

Another is childhood experiences of violence.

Socio-economic elements, such as poverty, unemployment and inadequate living conditions, underpin violence, mainly for younger men. Feelings of stress, frustration and humiliation, combined with substance abuse (chiefly alcohol), inequitable gender norms and the availability of weapons, especially firearms, often results in violent behaviour.

Given what studies say about the determinants of violence, I predicted during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 that South Africa would soon face a crime catastrophe. The pandemic and lockdown regulations had increased poverty, unemployment and food insecurity. This would exacerbate existing risk factors for violence, such as:

- domestic abuse

- learners dropping out of school

- diminishing prospects of meaningful jobs, especially for young, marginalised men.

In 2021/22 there was a significant increase in all categories of violent crime.

Since then there’s been no reduction in these risks, especially food insecurity, youth unemployment, child abuse and the school dropout rate. The murder rate per capita has increased from 33.5 per 100,000 during the COVID-19 period (2020/21) to 45 per 100,000 in 2022/23.

Police and the prevention of violent crime

Even though the police are not able to do anything directly about many of the underlying risk factors for violence, studies have shown that specific policing interventions can make a difference in reducing violent crime.

The police can work closely with communities to devise cooperative solutions to crime problems. They can also collect and use relevant intelligence to design and implement evidence-based crime prevention actions. These should focus on the areas where criminal offending is most concentrated, and on the situations that tend to drive that behaviour.

Interventions require a competent, adequately resourced and professional police organisation and a fair and effective criminal justice system.

Since the 1990s the work of the police has included community-oriented approaches. Best practice is for police to treat community safety groups as equal partners. Solutions to crime problems are co-created.

But the police’s approach has been the converse. They have co-opted community safety groups, such as community police forums and neighbourhood watches, to be force multipliers. Studies have shown that such a method is often ineffective.

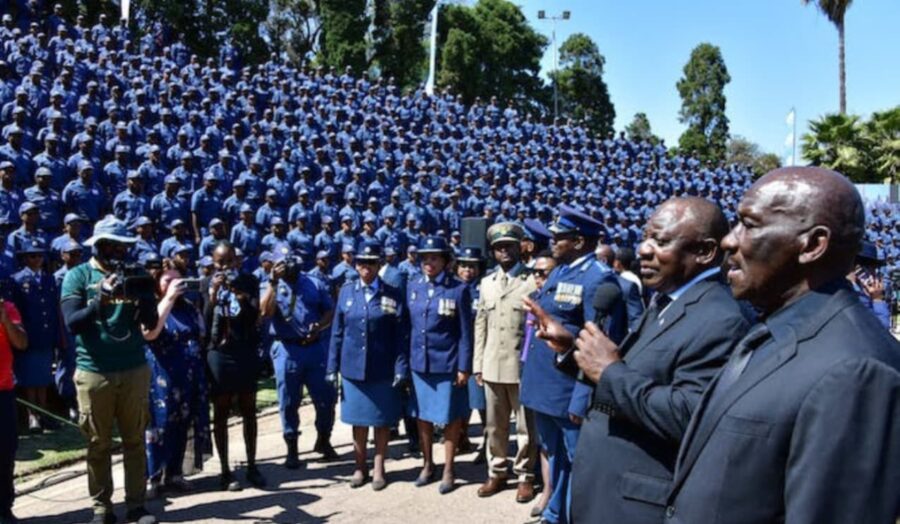

For the past three decades, South African police have prioritised militarised policing approaches, such as Operation Shanela (“to sweep” in isiZulu). They encourage police to be more forceful in their interactions with alleged criminals.

There is very little evidence to suggest that militarised policing brings down violent crime rates. Instead, it can erode public trust in the police. This is certainly evident in South Africa, where only 27% of the population view the police as trustworthy (from 47% in 1999).

Police effectiveness in combating crime has also been undermined by declining personnel numbers. In 2018, there were 150,639 police personnel, but this is now 140,048. There has also been a substantial decline in the police reserve force.

High levels of crime have placed considerable pressure on the criminal justice system too. Conviction rates for violent crime are very low. For example, between 2019/20 and 2021/22, police recorded 66,486 murder cases. Of these, only 8,103 (12%) resulted in a guilty verdict.

What can be done?

The good news is that the government does not exclusively depend on policing plans to tackle crime. It has also developed multi-departmental and evidence-based strategies and plans to prevent crime. These are derived from Chapter 12 of the National Development Plan. It calls for:

- police to be more professional, demilitarised and work in partnership with communities

- an improved criminal justice system

- an integrated crime prevention strategy.

In 2022 the cabinet approved the Integrated Crime and Violence Prevention Strategy. It seeks to achieve a whole-of-government and whole-of-society approach given the multi-dimensional nature of the risk factors that drive violent crime. Furthermore, this strategy encourages the government and other elements of society to jointly address common crime problems and collaboratively determine prevention strategies, especially at the community level.

ALSO READ: Eastern Cape sports ground still unfinished after millions spent

There was also the recognition that various government departments (and not just the police) needed to work closely with civil society and the private sector to drive down crime levels.

The problem is that the implementation of the strategy is in limbo. No government agency has been willing to take responsibility for it. That’s because there is no direct budgetary allocation, given the highly constrained government purse.

High levels of crime and low levels of policing have substantial negative effects on economic performance. So investing adequate resources to carry out the Integrated Crime and Violence Prevention Strategy will not only reduce violent crime but also contribute to economic growth.

Guy Lamb, Criminologist / Senior Lecturer, Stellenbosch University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.