South Africa Racing to Produce Masks Needed to Fight the Virus

After a slow start, production has been ramped up… writes Raymond Joseph, from GroundUp. A race against the clock is underway to source vitally needed masks and other personal protection equipment (PPE) for health workers at the frontline of the Covid-19 pandemic. With South Africa able to only produce 10% of the medical-grade masks it […]

After a slow start, production has been ramped up… writes Raymond Joseph, from GroundUp.

A race against the clock is underway to source vitally needed masks and other personal protection equipment (PPE) for health workers at the frontline of the Covid-19 pandemic.

With South Africa able to only produce 10% of the medical-grade masks it needs, a dual strategy of sourcing stock abroad and ramping up local production is underway, according to Stavros Nicolau, who heads up Business Unity SA’s (BUSA) Healthcare workgroup.

The Healthcare workgroup is one of several that have been set up, with big business working alongside the government to prepare for Covid-19.

“This has been a big wake up call and our response has been to engage with suppliers, both manufacturers and importers,” Nicolau told GroundUp in a telephone interview. The intention is to cut through red tape and help facilitate and speed up imports, while also ramping up local production.

“We have costed an eight week supply at between R1.6-billion and R1.7-billion and after that normal stocking can kick in,” says Nicolau. “But if there is a massive spike we are in the dwang.”

PPE worth R400 million has already been acquired, with pipeline funding for a further R360 million, according to the BUSA statement issued last week. The already procured stock includes 900,000 sterile gloves; 20,000 face shields; 1.12 million N95-type masks, 6 million surgical masks for healthcare workers, and 8.5 million surgical masks for patients. Included in this newly-acquired stockpile are also 200 ventilators.

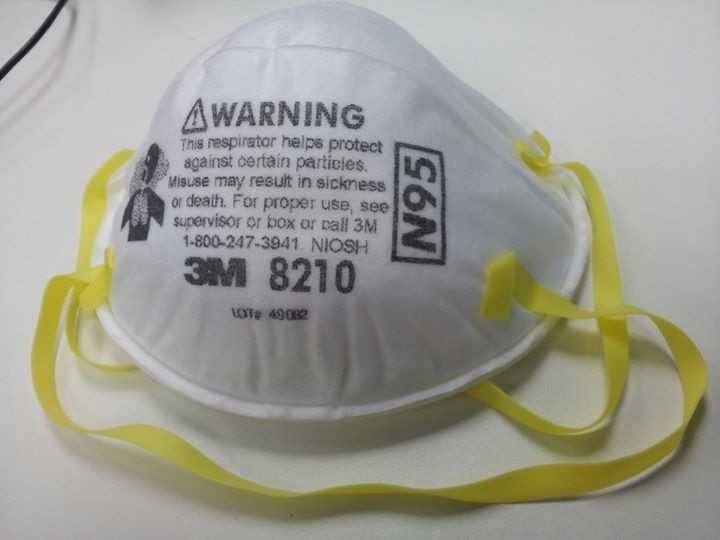

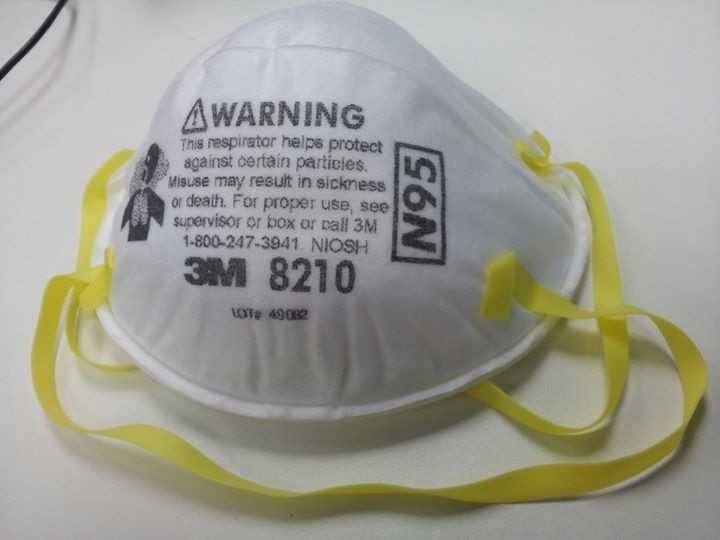

The N95-type mask — known as FFP2 masks in South Africa, which uses European specifications — are used in ICU units and by medical and laboratory personnel working in areas where there is a high possibility of contagion. They are also used in some areas on mines, car body respraying shops and high risk areas on construction sites. Triple-ply surgical masks are used in operating theatres, while medical personnel working in lower risk areas use masks that offer a lower degree of protection.

Another source of PPE equipment came from an appeal to businesses in lockdown, like mining companies, to donate supplies. “We had had a massive response,” says Nicolau.

In South Africa, N95 and equivalent masks are the minimum requirement in the mining sector, according to Ben Smith, co-owner of Gauteng-based Greenline Respiratory Masks, one of a handful of local manufacturers of these masks.

“But the imminent opening of the mines will place a huge demand on supplies and may restrict the available stocks for the healthcare sector,” he warns.

“To be honest, we were initially not — and still aren’t — in a comfortable space with PPE. The delay meant that … we are competing against 180 other countries for supplies,” says Nicolau.

One of the immediate problems identified was that while the high-grade frontline N95-equivalent masks were being produced locally, other masks were not, as it had been cheaper to import them.

The upside of South Africa being hit relatively late by the pandemic is that it has been able to learn from international experience. “But the downside is that we came late to the supply chain when governments had begun to tighten up on exports, and continue to do so,” says Nicolau. “Another problem was that the cost of PPE on the international market is priced in dollars and demand far exceeded supply.”

South Africa clamped down on the export of some products on 27 March, when DTI Minister Ebrahim Patel issued a Government Gazette notice regulating the export of certain equipment and PPE. In terms of the COVID -19 Export Control Regulation certain types of masks and breathing equipment and components may not be exported without a permit. Also included on the list is the malaria drug hydroxychloroquine which is being tested in clinical trials for treating Covid-19.

Until the current crisis, PPE had largely been restricted to ICU units, but with the pandemic, supplies are needed to cover a far larger number of frontline medical personnel who may come into contact with infected people “It is essential to make plans for the optimal use of what we have”, says Nicolau.

With the call by Health Minister Zweli Mkhize for everyone to wear a mask in public, guidelines have been supplied to the clothing industry for the production of masks sold to the public. A list of suppliers of materials that can be used for them has also been circulated.

The manufacturer

Greenline Respiratory Masks in Gauteng, one of six South African manufacturers of N95-equivalent masks, has ramped up production and is now “running six days a week, 24 hours a day” according to co-owner Ben Smith.

Before the Covid-19 pandemic, Greenline mainly supplied mining and other industries. Production has now been increased to 1.2 million masks a month and Greenline plans to produce an additional one million a month by June when new equipment is up-and-running. The company is also aiming to produce 3-ply surgical grade masks for the first time, and to turn out 1.5 million a day by then.

“Our biggest challenge now is obtaining the filtration material,” Smith told GroundUp in a telephone interview. This material is imported and the cost has skyrocketed from $36 to $176 per square metre because of worldwide demand. US suppliers stopped taking new orders as early as February.

Greenline had supplied 250,000 masks to Wuhan, the Chinese city that was at the epicentre of the pandemic, in March after a Red Cross appeal, says Smith. The company also supplied smaller quantities of masks to Hong Kong and Italy but has now stopped exports.

He says the South African government was initially slow to order stock. “We were getting inquiries from all over the world, from Angola, Finland, Germany, from the British … but nothing from South Africa.”

All that changed on 27 March, the day before South Africa announced its first Covid-19-related death, when Greenline received its first call from the Department of Trade and Industry. Since then “the government has been very proactive”, says Smith.

Masks that previously cost R2 to R2.50 each to import are now costing between R40 and R50, says Smith. A higher grade surgical mask, which previously cost between R9 and R12 to import, is now costing up to R70 a unit.

Many of South Africa’s intensive care clinicians are also anaesthetists. CEO of the South African Society of Anaesthesiologists (SASA), Natalie Zimmerman, says PPE stock is “only just beginning to get to the frontlines, where it is needed”.

“We are just putting things in place so that not only do the critical nurses, doctors, porters, and all the ancillary hospital staff have the PPE that they need, but they also know they will continue to get replenished stock for the patients still to come.”

While it has been impossible to gauge the situation regarding nurses and masks across the country, a senior Netcare staff member in Cape Town says there is a “chronic shortage” of masks.

She says used masks — which previously would have been discarded after use — were being re-sterilised with an ultraviolet machine and returned to the user the next day.

This was denied by Dr Anchen Laubscher, group medical director of Netcare. He said the group might in future consider the sterilisation and reuse of N95 masks only. This was based on an FDA-approved process supported by conducted studies done at Duke University, he says.

“Although these studies support up to 50 re-uses, Netcare, in contrast, is targeting only five re-uses. Ultraviolet light and hydrogen peroxide fogging are widely used in the world to effectively sterilise N95 masks, and as with all such matters Netcare will only be guided by accredited studies.”

Netcare had so far spent R300 million on “additional, appropriate personal protective equipment” to ensure the safety of staff “while they work in the frontline combatting the Covid-19 pandemic,” he says.

A doctor working at a major private hospital in Cape Town says he had arrived for a surgery last week only to discover that there were no surgical masks available. Closed circuit television cameras showed that a member of staff had stolen the entire stock. “It’s not as if he took a few for his family. The quantity suggests they were stolen to sell.”

On nurses’ sites on Facebook there has been active discussion of the mask situation, but GroundUp has chosen not to name people as they might be victimised.

One nurse wrote that in a private hospital in Johannesburg, nurses were using the same mask for seven days.

Another nurse wrote that she was expected to use the same mask for five shifts, which is equivalent to 60 hours.

SASA’s Zimmelman says: “Supply is not yet secure enough, and does not feel secure enough. Sometimes this limits access to those who should have access. Sometimes, it includes trying solutions like reuse. At this stage, despite there being some investigation and evidence still being gathered, there is no guaranteed way to ensure that any PPE that is reused is safe or as effective when reused. Until we are sure of this, we do not advocate any such efforts as we cannot guarantee the safety of our healthcare workers.”

Published originally on GroundUp / © 2020 GroundUp.