Report shows South Africa is failing to live up to its constitution

The end of apartheid in 1994 and advent of constitutional democracy resulted in major societal changes in South Africa. The aim was to forge a “united and democratic” society. The new nation was to be based on justice and human rights. The country’s constitution commits the government to take remedial action to address the legacy […]

The end of apartheid in 1994 and advent of constitutional democracy resulted in major societal changes in South Africa. The aim was to forge a “united and democratic” society. The new nation was to be based on justice and human rights.

The country’s constitution commits the government to take remedial action to address the legacy of past discrimination and injustice. It must improve the quality of life of all citizens and promote equality. It must also enable people to achieve their potential and promote nation-building.

Initially, this was to be achieved through the Reconstruction and Development Programme macroeconomic policy. It sought to promote the socioeconomic inclusion of those who had been excluded during colonialism and apartheid. It also aimed to combat disparities and discrimination on the basis of race, gender and disability. Since then, other macroeconomic policies have included the Growth, Employment and Redistribution and Accelerated and Shared Growth Initiative for South Africa policies. The current National Development Plan, adopted in 2012, seeks to eradicate poverty and inequality by 2030.

Last year, my colleagues and I at the University of Johannesburg, Mapungubwe Institute for Social Reflection and the Presidency of South Africa examined how the country had fared in achieving these goals and the challenges encountered.

Our report, Macro Social Report 2022, builds on the first report published by the presidency in 2006. The 2006 report concluded that the government had succeeded in improving the quality of life for citizens. This greatly contributed to a sense of unity, national pride and reconciliation.

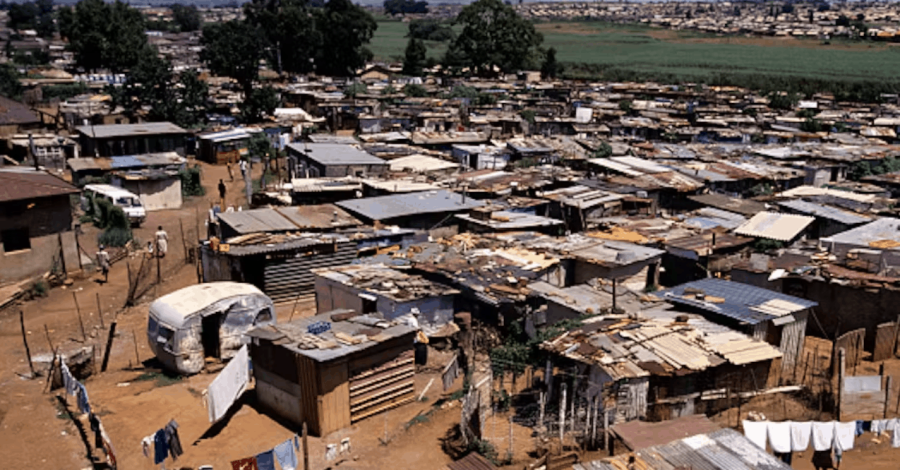

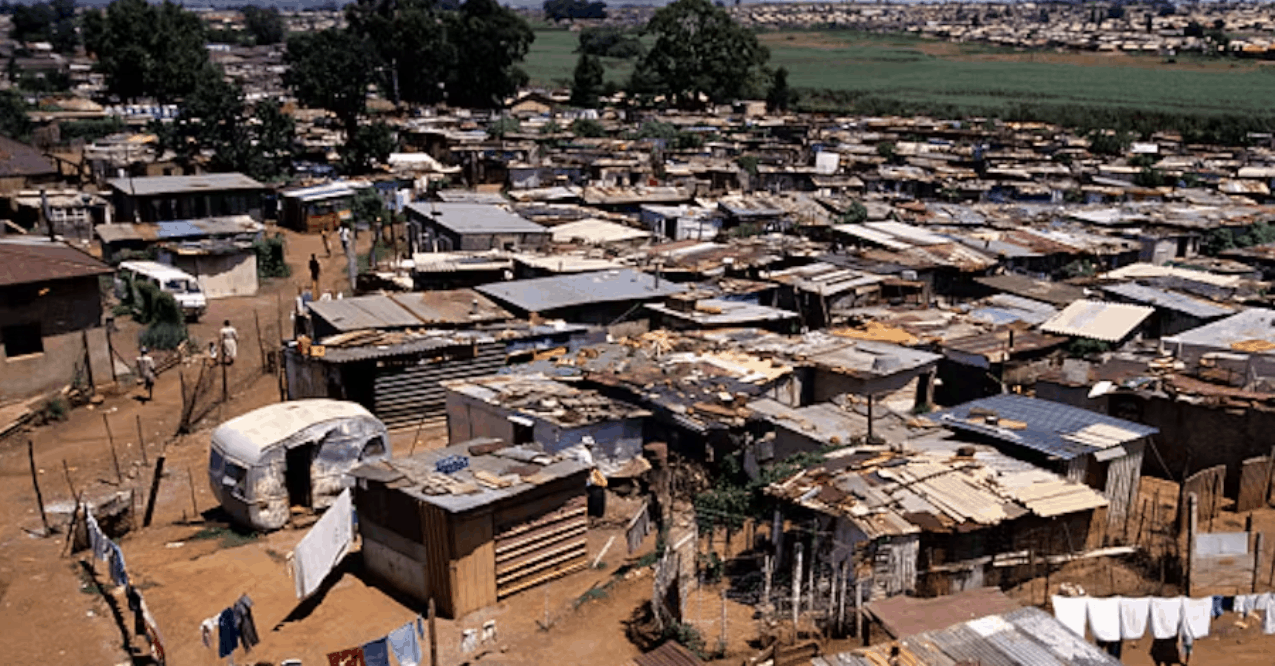

However, the 2006 report found that persistent inequality, crime, micro-level racism (racism experienced at an individual level) and mass migration to urban areas were countering any positive gains.

The updated 2022 report explored social structure and social mobility (ability of people to elevate their social status) and demographics of “race”, language, age, gender and disability. We also considered migration, causes of mortality, crime, social cohesion and the organisation of social life (how social groups are formed and interact with each other) as well as social networks (social and personal relationships).

The findings show a decline in essential socio-economic indicators since 2006. Most South Africans continue to face socio-economic exclusion and persistent discrimination on the basis of “race”, gender and disability. The findings matter because they show that the government has been unable to fully uphold the rights enshrined in the country’s globally revered constitution.

A poor performance

The report is based on relevant primary and secondary literature obtained from academic publications, government reviews and international institutions which specialise in socioeconomic and development policy. The research also included interviews with ordinary citizens in order to capture their lived experiences.

We found that South Africa still had a dual economy. Wealth is concentrated in the hands of a white minority. The country is one of the most unequal globally.

Extreme inequality has a profound impact on social and personal relationships as well as social cohesion. The major gap between rich and poor makes it difficult for people to relate to one another and form strong bonds.

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated poverty and inequality. According to World Bank estimates, South Africa’s poverty rate was 63% percent in 2022. Poverty is most pervasive among black people: 64% of Black, 41% of Coloured, 6% Indians and 1% White South Africans live in poverty.

The quality of basic services in some communities is poor.

South Africa ranks the worst globally in terms of intergenerational income mobility (the ability of children to change their level of income compared to their parents). Limited access to quality education has prevented many people from moving to middle class status. This has prevented the growth of a dynamic middle class.

We also found persistent racial disparities. This causes unequal societal power relations (one “racial” group holding power over others) and has a negative impact on social cohesion.

White and Indian people have living conditions, education patterns (for example, access to higher education) and employment outcomes that far surpass those of the coloured and black populations.

White and Indian women benefit disproportionately from redress policies compared to coloured and black women. Black women continue to shoulder a double burden in that they must contend with both racism and patriarchy. They are underrepresented across senior and intermediary occupational positions.

While some good progress has been made on gender rights and women’s participation in politics (as shown by the engagement and representation of women in government), people with disability are still largely marginalised.

Only marginal progress has been made in reducing crime. Case numbers of serious crimes went down by only 11% between 2015 and 2020. South Africa still has high crime rates.

On a more positive note, we found that mortality rates had dropped since 2006. Fewer people are dying prematurely. This has mainly been due to the government’s rollout of antiretrovirals since 2008.

Lastly, the report shows nation-building efforts have been undermined by growing inequalities, decline in good governance and persistent corruption. This has been evident in unethical political leadership, state capture, institutional decay and low levels of public trust in government.

Progress undermined

The socioeconomic and political changes South Africa made in the first decade of democracy produced positive results. But these have been undermined by weak governance and poor economic performance since 2006.

Addressing the socioeconomic and political challenges will be indispensable to the strengthening and consolidation of its democracy.

Social cohesion programmes and government initiatives must address these pressing concerns if the country is to build a close-knit society.![]()

Marcel Nagar, Senior Postdoctoral Research Fellow, University of Johannesburg

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.