Project from Iceland to tackle drinking and drug use among children in George

George, a town of about 200,000 people in the Western Cape, is taking inspiration from Iceland to reduce substance use among young people. An unlikely coalition has been formed, consisting of community and activist organisations, schools, the George Municipality, police, and provincial government departments. George is taking inspiration from Iceland to reduce substance use among […]

George, a town of about 200,000 people in the Western Cape, is taking inspiration from Iceland to reduce substance use among young people. An unlikely coalition has been formed, consisting of community and activist organisations, schools, the George Municipality, police, and provincial government departments.

- George is taking inspiration from Iceland to reduce substance use among young people.

- The Icelandic Prevention Model has had success in reducing substance use.

- A pilot survey done last year shows that 47% of 13 and 14-year-olds at a high school in George have been drunk in their lifetime, and 26% have smoked marijuana.

- The project will focus on strengthening family and community connections and will be led by a coalition of activist organisations, government departments, and the police.

In 1998, Iceland had a substance use problem, with 42% of 15 and 16-year-olds saying they had been drunk in the last 30 days. By 2016, the country had been able to reduce this figure to just 5%. Cannabis use went down from 17% to 7% and cigarette smoking fell from 23% to 3% during the same period.

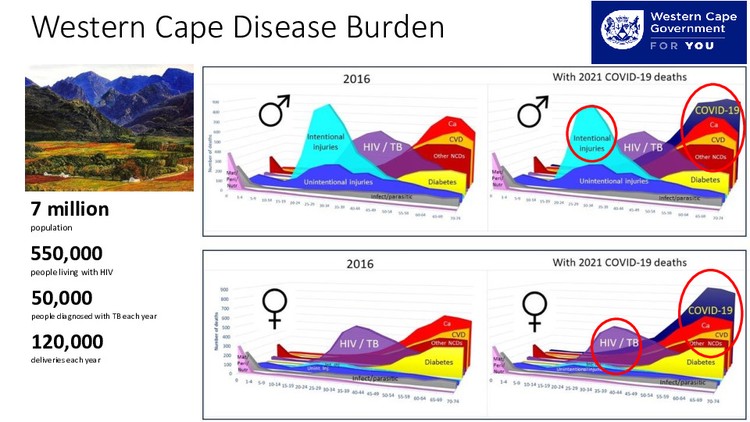

South Africa today is experiencing widespread substance use among young people. Communities across the country are struggling to deal with the harm caused by substance use. In 2021, intentional injuries, which are often related to alcohol and other substances, caused more premature deaths among men in the Western Cape than all diseases except Covid.

Iceland’s approach has been dubbed the “Icelandic Prevention Model” and focuses on data collection, coalitions, and community engagement to improve the social environment for children in order to reduce the risks of substance use.

An Icelandic organisation called Planet Youth is exporting the prevention model to countries around the world. The Planet Youth programme has been adopted in 15 countries, including Mexico, Chile, Ireland, Belgium, and Australia. The community of George is now bringing Planet Youth to South Africa.

“It hurts me to see what society does to us,” George resident Gustav Appels told attendees at the official Planet Youth launch on 3 February. Appels matriculated in 2021 and is involved in several community projects, including a soup kitchen.

“I want to tell Planet Youth: you have a job to do, to go to our various communities and serve them. Not just our youth but our parents, showing them we care and we love them,” Appels said.

The Planet Youth process starts with surveys that show the extent of substance use and the social factors that influence a child’s chance of using substances. The data is then used to design and implement community-based initiatives focused on strengthening family connections and incentivising children to take part in sports and cultural activities.

A pilot survey, done in November 2022 at one high school in George, found that 47% of 13 and 14-year-olds had been drunk at least once in their lifetime and 26% had been drunk in the last 30 days. More than half of the participants had used a hookah pipe and a quarter had smoked marijuana.

The survey also found that substance use is higher among children who do not spend time with their parents over weekends or whose parents or guardians do not know where they are in the evenings.

Teenagers whose parents strongly disapproved of substance use were less likely to use substances. Substance use was higher among teenagers who found school useless and those who spent time outside after 10pm were more likely to get drunk, smoke hookah pipes, or use marijuana, the survey found.

The Planet Youth project in George is still in its early stages. In the coming months, all grade 8 and 9 learners in George will anonymously participate in surveys. The results will then be communicated to the schools, parents, and community leaders, and the community will decide on which initiatives to implement. This is done in consultation with the Planet Youth representatives in Iceland.

The initiatives will be aimed mainly at primary school learners, but learners in grades 8 and 9 will be surveyed every two years to measure progress. Initiatives may include increased access to sports and cultural activities. There will also be workshops with parents and access to mental health care and rehabilitation services may also be improved.

“This is going to be big. This has never been done before,” said Lynn de Grange, Head of Learner Support for the Eden district. She said that the Planet Youth programme’s “whole of society approach” will assist the Education Department in improving the well-being of learners.

Will this work?

George has an unemployment rate of more than 20%, whereas only 4% of Iceland’s population is unemployed. Incomes are much less unequal in Iceland than in George. An average of 68 murders are reported in George every year, compared to five in Iceland.

Iceland’s success was aided by the ability of the government to implement far-reaching interventions quickly and efficiently. A nationwide curfew requires adolescents to be indoors by 10pm. Laws were changed to ban alcohol advertising, and state funding for sport and cultural organisations was increased. Families received vouchers worth $420 per child per year.

Planet Youth’s CEO Pall Ríkhardsson emphasises that the project is not a programme but a process. “What works in Iceland does not necessarily work in South Africa,” said Ríkhardsson. Each country Planet Youth operates in, from Mexico to Belgium, has a different socio-economic context which requires unique interventions. But the guiding principles, Ríkhardsson said, are universally applicable.

“In every community we work in, the natural forces are always the same,” Ríkhardsson said, “Parents love their kids, they want what’s best for the kids. We focus on harnessing that force.”

Whether community projects in George will enjoy the necessary funding and support to make a significant impact on substance use remains to be seen. The success of Planet Youth in George will also depend on buy-in from parents and the strength of the coalition of organisations and government departments.

It is too soon to conclude whether Planet Youth has been successful in other countries, as most of the countries only started implementing the model after 2020.

But what has already been achieved in George is remarkable. SAHARA, an activist organisation that does harm reduction and rehabilitation work, has been advocating for Planet Youth to be implemented for more than five years.

“We cannot afford to deal with the consequences of substance use,” said SAHARA’s director Hermann Reuter. The harm caused by substance use impacts every sphere of society and the consequences are expensive. “All government departments will benefit from prevention,” Reuter said.

The Western Cape Department of Health came on board in the early stages, followed by the departments of Education, Culture, Arts and Sport, and Social Development. The University of Cape Town is a partner and funder. The South African Police Service (SAPS) is also a coalition member.

YearBeyond, which trains and employs young people to serve their communities with money from the national Jobs Fund and the Western Cape government, has allocated 50 “YeBoneers” to work at schools in George to support SAHARA and the Planet Youth programme.

The successful launch at the town hall was attended by representatives from the coalition partners, community leaders, and young people. It was an image of a community united behind a shared problem and an ambitious dream to solve it.