Nontsikelelo Zwedala: an unsung hero of the struggle for HIV medicines

Nontsikelelo Zwedala, an activist at the forefront of the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) protests in the early 2000s, died this month at the age of 52. We asked Zackie Achmat, TAC leader at the time that Nontsikelelo was active in the organisation, to write an obituary for her. Our soft Ntsiki, with a will of […]

Nontsikelelo Zwedala, an activist at the forefront of the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) protests in the early 2000s, died this month at the age of 52. We asked Zackie Achmat, TAC leader at the time that Nontsikelelo was active in the organisation, to write an obituary for her.

Our soft Ntsiki, with a will of steel, is no more.

I started writing these words last year as a historical tribute to Nontsikelelo Zwedala and Christopher Moraka as part of a paper on TAC’s campaign for the antifungal medicine fluconazole. Nontsikelelo was still alive.

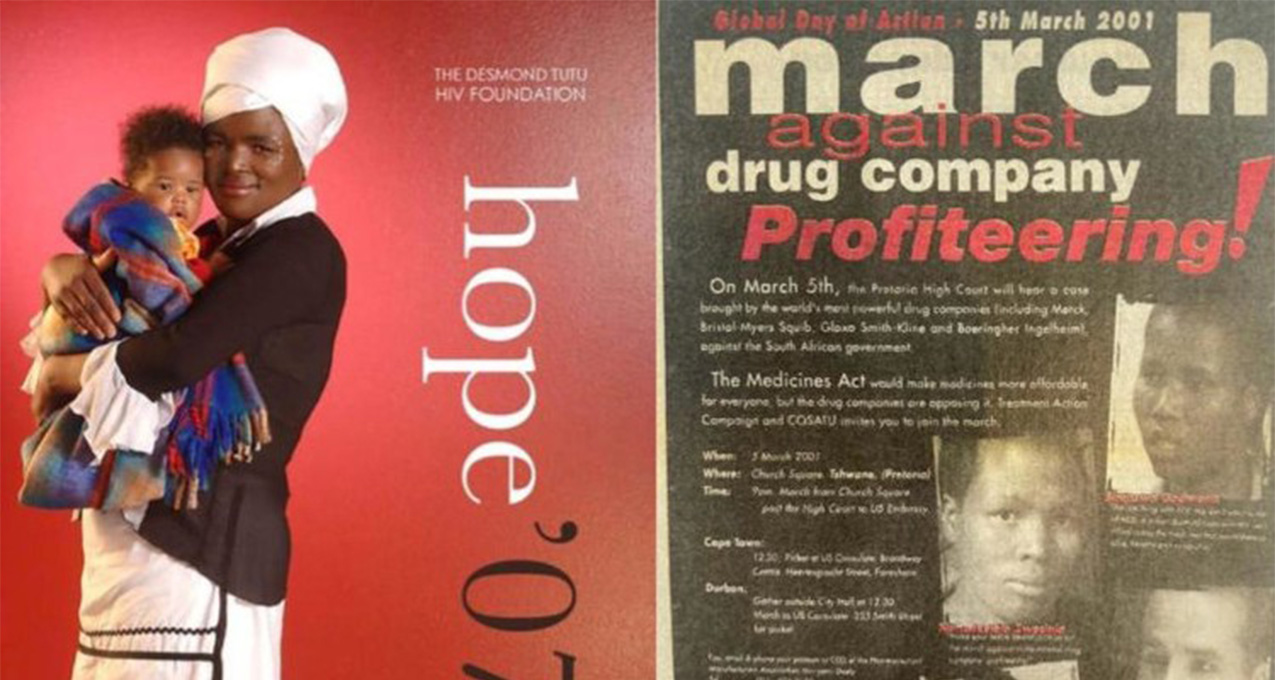

We launched our campaign on 17 October 2000 and named it the Christopher Moraka Defiance Campaign Against Patent Abuse, in which TAC imported fluconazole from Thailand in defiance of patent laws.

Nontsikelo could have died before Christopher, her partner, because she also became desperately ill. He died, yet she lived, because she was treated and he was not. Christopher died because Pfizer’s price for fluconazole, a life-saving medicine, was unaffordable for the state and most private citizens. Christopher could also have lived with antiretroviral medicines (ARVs). However, he could not exercise his right to health and, consequently, his right to life. He died a few months before the campaign was launched.

The story of TAC’s decision to defy patent law has many strands but none so moving as the relationship between Christopher and Nontsikelelo. Their influence in sparking our movement cannot be overstated.

In his death, Christopher became a global symbol for a revolt against Pfizer and other drug companies, while Nontsikelelo became an unsung warrior in the struggle against drug companies. She helped win against Pfizer. Then she was there in TAC’s challenge to 39 drug companies who took the South African government to court. She was also in every battle against the denialism of the South African government.

In September 2002, Nontsikelelo explained her struggle for life, as HIV-related illnesses wracked her body, in an affidavit. She was the second complainant to the Competition Commission against drug company giants GlaxoSmithKline and Boehringer Ingelheim, demanding access to generic ARVs. Hazel Tau, another TAC leader also living with HIV, was the first complainant.

In March 1998, Nontsikelelo was diagnosed with HIV and told by the doctor:

“I should wait for my death.”

At that time, Nontsikelelo had TB and a fungal infection on her hands and feet. She explained how the fungal infection caused her pain:

“… if I put water on it then blood used to come out from the cracks on my hands and feet.”

After treatment with fluconazole, her health improved. Then government stopped providing Pfizer’s fluconazole because of the cost.

In 2000, Nontisikelelo’s TB and fungal infections returned. Her CD4 count, which indicates the strength of the immune system, was 14. The CD4 count of a healthy adult is between 800 and 1200. She lost 30kg. The clinic treated her TB but could not treat her fungal infections which required fluconazole made by Pfizer. She could not afford it. Eight months later, Nontsikelelo’s HIV viral load measured millions per drop of blood.

Dr Hermann Reuter, a TAC leader and Médecins Sans Frontières doctor, arranged that she could join an ARV clinical trial for a year because there was no public health programme. The drug companies would only provide medicines for two years after the clinical trial. Nontsikelelo gained 16kg of weight after starting ARVs. Her CD4 count recovered from 14 to 242 and her viral load significantly reduced. Nontsikelelo explained her experience as follows:

“When I was sick, my mind was not working well. My skin was rough. I had a rash all over. I used to forget everything – even my child. But now my mind is working well and everything is alright. Now that I’m working I can help other people living with HIV and I can help my son and sister and mother. My family knows that I am on treatment and they are happy now that I am healthy and not sick like before. They got worried when I was sick. I know many people who are very sick … I wish that they could have treatment. It would be very good for them because they can live the life I am living now – from a deathbed to working.

“The doctors have told me that the drugs that I am on now cost about R2,000 a month and I am told that some ARV regimens cost about R1,300. … there is no way that I can afford to buy such expensive drugs [if I am made to pay for them myself].”

One of the reasons that girded her determination to live and revolt against drug companies was explained by Nontsikelelo:

“In 2000 my boyfriend Christopher Moraka passed away because of AIDS. He had no access to treatment. He was suffering from thrush. If he had treatment he would have lived.”

Nontsikelelo joined the Gugulethu TAC Branch started by Mkhanyiseli Mpalali, Mandla Majola, Sipho Mthathi, Hermann Reuter with the late Queenie Qiza and many others. As TAC leaders they played a central role in the political and treatment education of their branch and the whole movement.

As a movement, the TAC is known for its struggle to access ARVs but in reality it was our struggle to access an ordinary essential medicine that changed the course of our battle against drug company profiteering. TAC’s struggle against Pfizer for fluconazole was one of the most important building blocks in our efforts to ensure that everyone who needed it could access HIV medicines for free and that the resistance of drug companies to generic ARVs was defeated.

Fuelled by pain, anxiety, and compassion, dispossessed people living with a death sentence were joined by their loved ones, comrades and allies in confronting one of the world’s most powerful economic cartels, which still has way too much influence with governments, especially the United States, and the World Trade Organisation. The drug companies and people living with HIV engaged in a life and death struggle.

In her last days, I learnt that Nontsikelelo was going blind with cataracts because she was on a long waiting list at Groote Schuur Hospital. She had also developed stomach ulcers and ultimately died of kidney failure.

One of the tragedies of TAC and movements across the world is that there is almost no attention given to the mental and physical health needs of older HIV survivors who are on ARV treatment. We are depressed, most of us are developing the illnesses that affect everyone in our country and we are lonely. As veterans of TAC’s struggle we have tremendous trauma because of watching our friends die painful deaths because of drug company profiteering but above all because of the criminal HIV denialism of former President Thabo Mbeki.

We, TAC veterans, can and will still play a radically productive role in political movements to save our own lives and to share the knowledge of education, organising, mobilising and movement building based on health justice, equality and freedom. In memory of, and, as a tribute to Nontsikelelo Zwedala, we must take care of each other and try to build a caring and just society. We must build a society that will be as gentle as Nontsikelelo, and with her steely determination to achieve a dignified life.

All Nontsikelelo’s comrades say to her family and all who loved her: we send our love, solidarity and condolences.

Nontsikelelo Zwedala (7 May 1970 to 13 March 2023) is survived by her four children Phikolomzi, Thobile, Ayola and Enathi Zwedala, her sisters Siziwe and Nomfaneleko Zwedala, and her two grandchildren Avene and Olwenene Zwedala.

Published originally on GroundUp | By Zackie Achmat