Nixon’s Decision to Delink the Dollar from Gold Still Hounds the IMF, South Africa and Africa

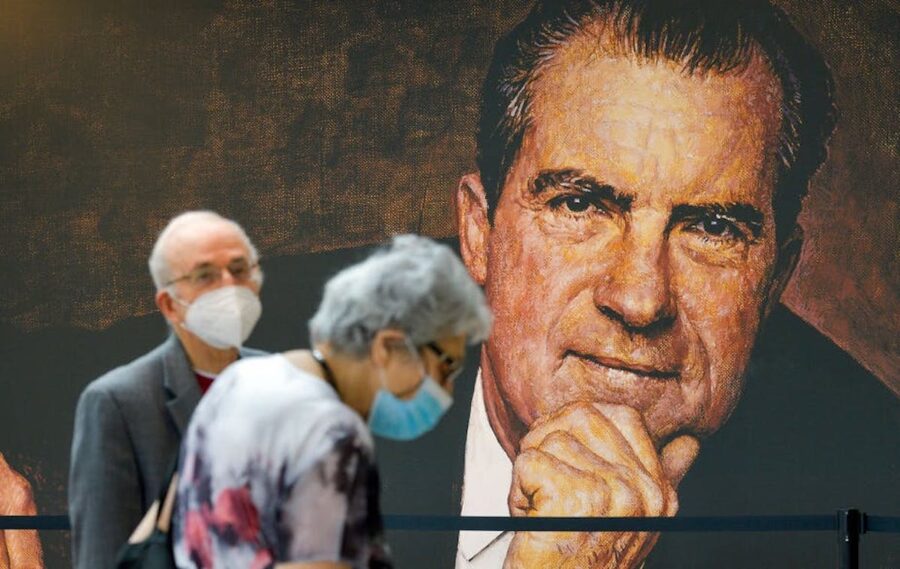

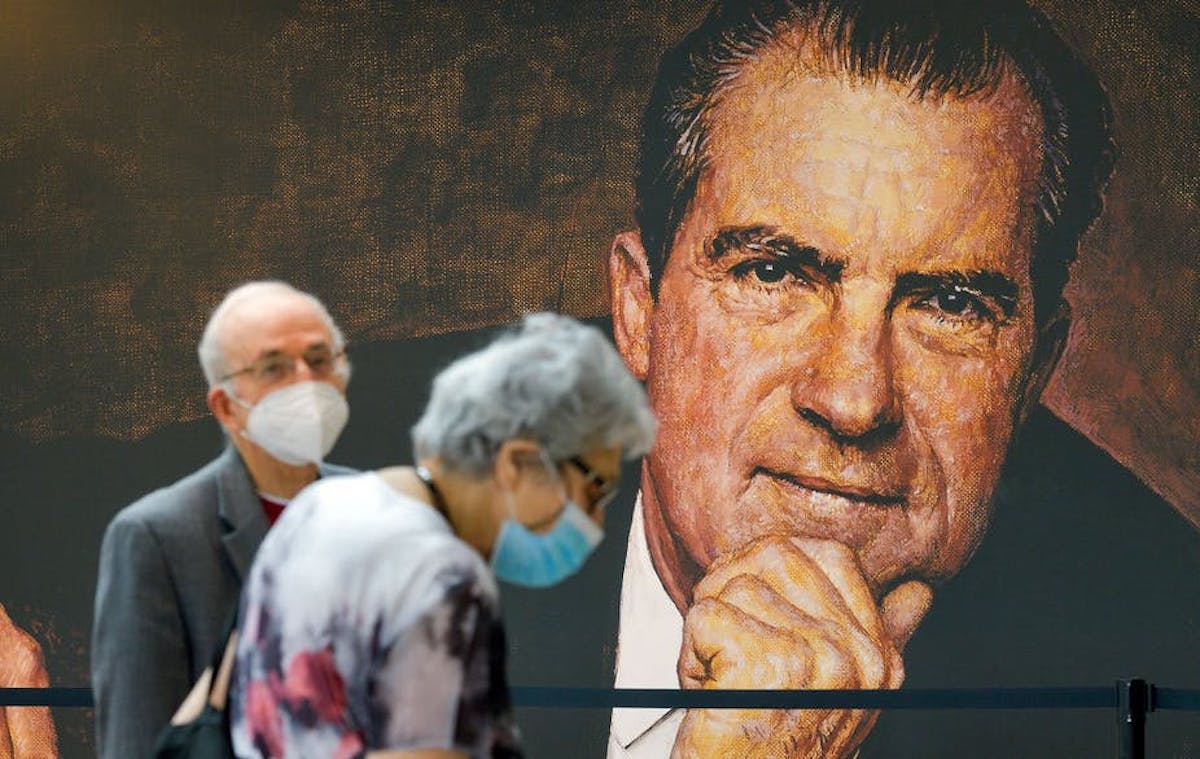

Nixon’s decision to delink the dollar from gold still hounds the IMF, South Africa and Africa. Five decades ago this month, US President Richard Nixon informed the world that the US would no longer honour its commitment to exchange US dollars for gold on demand. The commitment had been the foundation of the international monetary […]

Nixon’s decision to delink the dollar from gold still hounds the IMF, South Africa and Africa.

Five decades ago this month, US President Richard Nixon informed the world that the US would no longer honour its commitment to exchange US dollars for gold on demand. The commitment had been the foundation of the international monetary system created in 1944 at Bretton Woods, a conference established to regulate international financial order after the conclusion of the second world war. This system required each participating state to maintain a fixed par value for its currency in terms of the US dollar. In return, the US promised to freely exchange dollars for gold at the agreed price of US$35 dollars per ounce of gold.

Nixon’s action – announced on 15 August 1971 – had profound and long-lasting effects on the International Monetary Fund, South Africa and Africa.

Nixon’s decision breached the US’s treaty obligations. But he had little choice.

By 1970, the rest of the industrialised world had accumulated such large dollar holdings that the US did not have sufficient gold to credibly keep its gold window open. The situation was likely to continue deteriorating because in 1971 the US experienced its first trade deficit of the Twentieth Century.

In short, the US lacked the resources to manage the Bretton Woods system on its own.

Five years after Nixon’s decision, IMF member states agreed to end gold’s monetary role and, in effect, to move to a market-based system of floating exchange rates.

Nixon’s action 50 years ago continues to influence global economic governance. At the time the ripple effects for southern Africa were also profound.

One unintended consequence was that South Africa, at the time the world’s largest producer of gold, lost its position as a central player in the international monetary system. As a result, the South African apartheid regime became less important to the Western world. This contributed to South Africa colluding with the US to fight the Cubans and the Russians who were supporting the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) in their struggle for Angolan independence.

It also made it easier for other nations to support sanctions against South Africa, and, in the 1980s, to oppose future IMF and later commercial bank support for South Africa.

Nixon’s announcement and its aftermath also changed the IMF’s mission.

Change of direction for the IMF

During the Bretton Woods era, the IMF would meet annually with each of its member states to establish that they were following policies consistent with the maintenance of the par value of their currency. This placed limits on the issues the IMF would raise during these visits as well as on the range of officials with whom it needed to consult.

It also meant that, since all member states were participants in the same international monetary system, their ability to maintain the par value of their currency were influenced by the same variables. Moreover, since they were all potentially consumers of the IMF’s financial services – and during this time all member states did draw on its finances – they all would need to pay comparable attention to the IMF’s advice.

This was particularly relevant because the conditions that the IMF attached to its financial support was likely to be based on this advice.

The end of the par value system changed all this. If countries had no obligation to maintain any particular value for their currency what exactly was the IMF supposed to be monitoring in its annual mission to each country.

The treaty establishing the IMF had been amended. It now merely stipulated that the IMF should ensure that the member states were contributing to a stable system of exchange rates. This meant that the IMF had to monitor all the factors that could influence each countries’ ability to pay all their international obligations and keep the price of their exports competitive. Since almost any aspect of a state’s economy could affect the exchange rate, the IMF began to slowly expand the range of issues that they raised in their annual country visits. They began to incorporate issues such as food subsidies, labour policies, social spending, regulatory policies, trade policy, and the role of the state in the economy.

While the IMF’s surveillance reports were purely advisory, their impact varied according to the situation of each country. Countries that were rich and knew that they would not need IMF financial support could comfortably ignore its advice. After 1976 no rich country requested IMF financing until the European debt crisis in 2010. They thus regained the monetary sovereignty that they had surrendered to the IMF at Bretton Woods.

On the other hand, countries that anticipated that they would need IMF financing or the IMF’s approval of their policies, were forced to take the advice seriously. They knew it would determine either the conditions the IMF attached to financial support or their access to other sources of finance

To a differentiated world

The result was that after 1976 the IMF became an organisation that engaged with member states on a differentiated basis.

Some, knowing they would not need its services, could engage with the IMF essentially on a voluntary basis. Others, anticipating that in one way or another they would need to consume IMF services, were forced to treat the IMF with deference, knowing that that they had limited capacity to oppose its advice.

Unfortunately, given the weighted voting arrangements in the IMF, this differentiation also meant that the states with the dominant voice in the organisation did not depend on its services. Consequently, they could place demands on it without worrying about being accountable to those who would be most affected by their decisions.

This was a situation ripe with potential for abuse. For example, in the 1996 Asian crisis, the IMF’s most influential member states could refuse to support IMF financing for Asian countries unless they adopted economic policies that benefited the rich countries.

The IMF also found a new role for itself in the 1980s as the discipliner of countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America facing debt crises. It offered these states some financial support in return for their other creditors offering them complimentary relief and their compliance with various IMF policy conditions. Given the broad scope of the IMF’s mandate, these conditions were both intrusive into the affairs of their members states and consistent with the free market ideological preferences of its rich member states.

This resulted, for example, in the controversial structural adjustment policies that the IMF forced African states to follow in this period.

Long term impact

Nixon’s decision marked the end of exclusive US hegemony over the Western world. It also left the IMF without a clearly defined role. Under the leadership of the industrialized countries, it began to fashion a new more intrusive and ideological role as advisor to and financier for developing member states, including in Africa.

In addition, by unshackling exchange rates, Nixon began the process of globalizing finance and creating today’s global economy in which companies make decisions based on short-term financial considerations rather than on the real needs of people and society.![]()

Danny Bradlow, SARCHI Professor of International Development Law and African Economic Relations, University of Pretoria

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.