Limpopo learners keep tabs on river water quality

More than 200 schoolchildren in Limpopo have been trained to capture precious data about water quality from boreholes and rivers near their schools in a project linked to the United Nations and run by the University of the Western Cape (UWC). Citizen scientists trained through a University of the Western Cape project are helping to […]

More than 200 schoolchildren in Limpopo have been trained to capture precious data about water quality from boreholes and rivers near their schools in a project linked to the United Nations and run by the University of the Western Cape (UWC).

- Citizen scientists trained through a University of the Western Cape project are helping to train school children to monitor their environment.

- Data collected on river water quality is shared with an international programme.

- Plans are for the project to expand to other provinces.

For two days in May learners from Mara Primary, Komape Molapo Primary and Boetse Secondary School spent time in the field as part of the Diamonds on the Soles of Our Feet project.

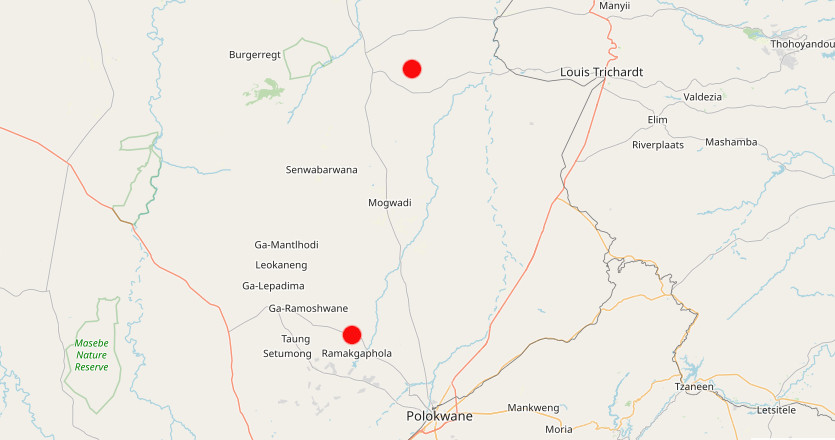

The project, founded in 2019, currently focuses on the Hout Catchment to the north of Polokwane. Members of the community are trained by experts from UWC and these “citizen scientists” train learners in their area.

The children are taught about water health, and how to measure phosphates and nitrates (which are usually pollutants from agriculture and poorly functioning sewage plants) using a freshwater test kit and a mini SASS (Stream Assessment Scoring System). SASS evaluates the health of a body of water body by measuring the number and diversity of invertebrates (small animals) in the water.

The data is entered into a system using cell phones and sent to a platform run by EarthWatch Europe. From here it is sent to the United Nations SDG 6.3 water portal which aims to bring safe drinking water to all as part of Sustainable Development Goal 6, one of the United Nations’ 17 global goals agreed to in 2015.

The importance of citizen scientists can be illustrated in the way volunteers in England have been helping to test for pollutants in rivers, and holding authorities to account for the deterioration of ecosystems.

“Water in South Africa is a scarce resource which must be taken care of,” says Murendeni Mavhungu, citizen scientist and field manager of the project. Murendeni says the goal is to create awareness and teach children and the community about water health.

The project first focused on measuring the impact of rainfall on borehole levels but has since expanded into checking water quality in nearby rivers. Learners start the project in class and then go into the field.

Mavhungu says they’re teaching the children about water health, vegetation and pollutants in rivers and ponds. He wants them to be able to take care of these water sources in the future. If water sources are not protected, “we’re going to have health problems, and water shortages, which might lead to famine,” he says. “Water is a precious resource, and it cannot be replaced by any other resource.”

The project was founded by Jacqueline Goldin, Associate Professor of Anthropology and Water Sciences at the Faculty of Natural Sciences at UWC.

“People who are on the ground are extremely knowledgeable, and we just need to tap into that. I think citizen science is a brilliant way of doing that,” says Goldin.

She says the name “Diamonds on the Soles of Our Feet” comes from the idea that citizen scientists are ‘diamonds’, “not just because they’re sparkling with the knowledge, but also because under their feet is all this experience and know-how.”

The aim is not only for them to collect data but to eventually run the project in their communities.

Brendon Basson and his mother Catherine are subsistence farmers in Buysdorp who have been trained as citizen scientists. Water for their farm drains off the nearby Soutpansberg mountain, and they also have boreholes for irrigation.

“I need to know if my water is safe,” says Basson. “People don’t know what is going on within the water bodies.” Citizen scientists are trying to educate their communities to protect their surrounding areas, and create “a relationship between them and nature”, he says.

Dorah Masehela is also a citizen scientist, from Ga-maleka. The issues she faces are very different from those in Buysdorp. In her village, she says government mismanagement and theft have reduced water supplies. Taps on the street and pumps that used to bring water from the river have been stolen and people have made their own water connections, draining off water before it reaches the taps.

She says if you don’t have access to a borehole, you have to walk hundreds of metres for water or buy it from someone who does have a borehole. It costs R2 to fill a 20 litre container or R250 to fill a 2,400 litre JoJo Tank. She makes sure to fill her JoJo tank which can last her several weeks. Masehela says she hopes the Diamonds on the Soles of Our Feet project will inspire young scientists and environmentalists. “They say that education is a tool. You educate one child, you educate a village.”

Goldin hopes to expand the work from Limpopo into other provinces. The project is funded by the Department of Science and Innovation and administered by the South African Agency for Science and Technology Advancement (SAASTA), part of the National Research Foundation. Officials from the Department of Water and Sanitation have approved the citizen scientist training protocols and monitor the process of data collection.

Published originally on GroundUp | By Ashraf Hendricks