Four ways to have hard conversations with your friends – without making things worse

It’s painful to watch someone you care about make what you perceive as bad life choices – we all want what’s best for our loved ones. This can be particularly hard when they are dating someone you don’t think is good, or right for them. Swifties (fans of Taylor Swift) have experienced this recently when […]

It’s painful to watch someone you care about make what you perceive as bad life choices – we all want what’s best for our loved ones. This can be particularly hard when they are dating someone you don’t think is good, or right for them.

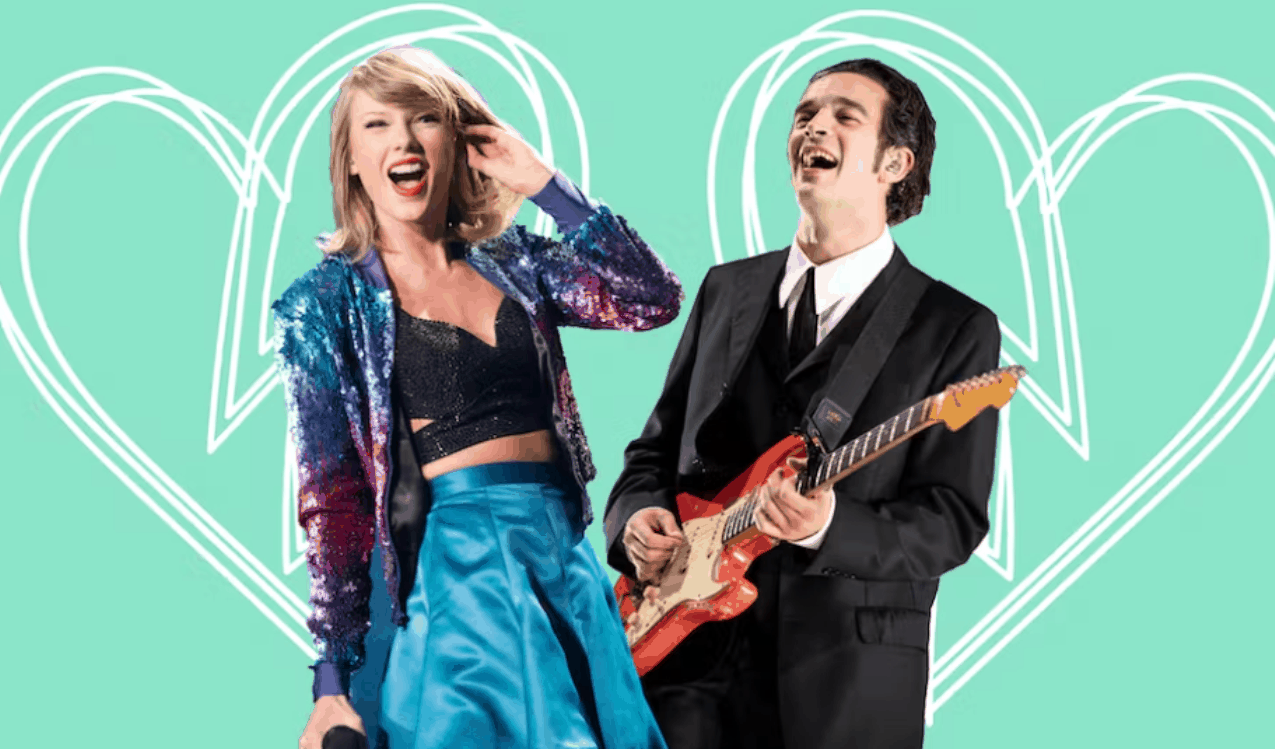

Swifties (fans of Taylor Swift) have experienced this recently when Taylor Swift was reported to be dating famed bad boy and “problematic” favourite Matt Healy from the band The 1975. Some fans form parasocial relationships with famous figures like Swift – this is where they feel like they have a close personal relationship with a celebrity and feel invested in them, while the celebrity has no idea who they are.

Taylor Swift’s actions are visible for public dissection and become fodder for viral social media content. As this new relationship dominated social media timelines, many of her fans found themselves wishing she would make a different choice.

Swifties called for her to end the relationship. For them, it was simple – Healy was no good for her. Swift seems to have listened as the pair are reported to have parted ways. But it’s not so easy to tell your real friends what to do with their lives, especially around matters of romance, love and sex.

Unwanted advice

Getting others to alter their behaviour when they haven’t asked for help can come across as insulting or as a “threat”.

This is because when you try to direct others’ behaviour, it involves two dimensions: one is entitlement (your power to tell them what to do) and the other is contingency (how difficult it would be for them to take that action).

This article is part of Quarter Life, a series about issues affecting those of us in our twenties and thirties. From the challenges of beginning a career and taking care of our mental health, to the excitement of starting a family, adopting a pet or just making friends as an adult. The articles in this series explore the questions and bring answers as we navigate this turbulent period of life.

Giving unsolicited advice is a high-entitlement move that suggests you know better – a hard thing to claim when you’re talking as an outsider about someone else’s private love life. And asking someone to break things off with someone they’ve committed to is a high-contingency act that requires serious effort, emotionally and otherwise.

This is frustrating because our opinions about our friends’ lives stem from wanting to help and support them. And sometimes, friends make choices that are not just unwise, but dangerous. Hard conversations only get harder if the other person doesn’t agree there’s a problem, or that they need to change anything.

1. Solid evidence

First, you need a good base of evidence before you start these conversations. You cannot simply assert a belief when it comes to other people’s experiences: you need to be able to provide concrete examples that they can remember, interpret and discuss.

You can use some of the same basic strategies used in research to understand and improve the situation: specific, agreed examples give us a shared point of reference for doing so. Having these shared references is critical if the other person doesn’t see a problem.

2. Increase their awareness of the impact

Second, you’ll have to get them to notice that the situation might feel wrong and/or how what they’re doing might be impacting others in a negative way.

To do this, try encouraging them to acknowledge and track evidence in their everyday life. Have they noticed how their partner treats parents and friends? How do they feel in public versus private with their partner? Are there discrepancies between what their partner says versus what they do? Help your friend recognise the problem first themselves and they might be easier to persuade that something needs to change.

3. Avoid conflict

Third, if there is a potential for conflict there are small things you can do to deal with it. For example, when you anticipate disagreement you can design what you say to head off possible misunderstandings or negative interpretations.

You might say “this is just how it seems to me”, or “I might not have the right idea” before you offer your view. You can also follow up on responses to check for possible misunderstandings as you go along. For example, you can keep asking questions to understand what a possible disagreement actually means – this approach is common in therapy.

A good tactic involves restating what they’ve said back to them to confirm you’ve got it right. You should ensure the other person feels carefully listened to and emotionally supported, even if there is a disagreement.

If you do encounter disagreement, it is important to avoid blaming the other person, or making exaggerated statements in the heat of the moment that they can easily reject.

However, this does not mean avoiding emotion altogether. Emotion is a normal and useful dimension of everyday social interaction, but be thoughtful. For instance, rather than showing frustration, emphasise your own concern and respect for your friend.

4. Baby steps

Finally, take an incremental approach. Suggest a small step that involves making them aware of the possible issues in their relationship and plan for future conversations.

Keep in mind you are unlikely to succeed in getting them to consider your viewpoint in a single conversation. The bigger the problem being addressed, the more work it takes and the longer it takes. It’s worth the struggle because it’s an investment in the future of your friend’s life. But until they agree something is wrong, they are unlikely to make any major changes.

Whether it was due to interventions from friends or not, Taylor Swift’s alleged bad relationship choice may have been undone – but it doesn’t always turn out that way. Sometimes you have to live with other people’s bad decisions, at least until they too recognise the problem.![]()

Jessica Robles, Lecturer in Social Psychology, Loughborough University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.