Eastern Cape school struggles to feed learners on just over three rand per child

A primary school in the Eastern Cape is struggling to put food on the plates of learners with the Department of Basic Education’s (DBE) current budget allocation of just R3.05 per child. The principal of an Eastern Cape primary school says she spends a significant amount of her time just sourcing food to feed learners. […]

A primary school in the Eastern Cape is struggling to put food on the plates of learners with the Department of Basic Education’s (DBE) current budget allocation of just R3.05 per child.

- The principal of an Eastern Cape primary school says she spends a significant amount of her time just sourcing food to feed learners.

- The school only gets R3.05 per learner for the daily meal and 59c for breakfast.

- Meals received through the National School Nutrition Programme are often the only meal learners will get all day.

- The Eastern Cape education department says it has received no reports of schools struggling to meet its menu requirements.

GroundUp recently spoke to a principal of a primary school in Makhanda. Her name has been withheld to protect her and the school from reprisal by the department. The principal says she spends a third of her time researching the cheapest food options to buy in order to make the daily meals for their learners.

The allocation per learner for one daily meal for the 2023/24 financial year is R3.05 for primary schools, R3.65 for secondary schools, R7.35 for rural school learners, and 59 cents for breakfast for all schools, according to the Eastern Cape Education Department spokesperson Mali Mtima.

The principal says they are struggling to make ends meet, especially since there is no provision for ingredients such as thickening agents, salt, oil or onions to improve flavour.

“As soon as you add things to make the meal appetising and to bulk it up, then you go over budget. So we are forced to make cuts. It is not always possible to put the stipulated meal on the learners’ plates,” said the principal.

She says the breakfast allocation per learner is only enough to give learners a half cup of instant porridge in the mornings. She says a growing child’s brain needs protein, and breakfast should rather be an egg or a glass of milk. However, they can’t afford to provide this.

The National School Nutrition Programme (NSNP) was set up by the government to “address hunger, malnutrition and micronutrient deficiencies in learners”. About 9.6 million learners are fed through this initiative on school days, according to the department’s recent parliamentary presentation on 16 May.

A conditional grant of R9.8-billion has been allocated to the nutrition programme for the 2023/2024 financial year.

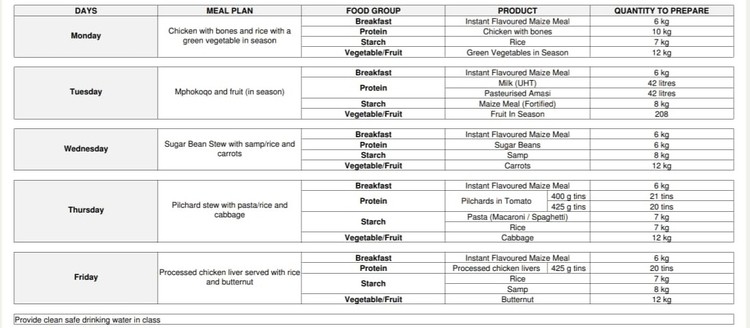

According to the department’s meal plan advisory, which is worked out by nutritionists, learner meals should consist of protein, starch, and at least one vegetable or fruit every day.

The meal plan has not kept up with inflation. Many schools struggle to stick to these guidelines every day to ensure that learners are still fed.

This is one of the menu meal plans sent to schools by the department.

Provincial education departments can either use a centralised or decentralised NSNP model to provide daily meals to their learners. All schools in the Eastern Cape follow this “decentralised” model, as do the Free State, Northern Cape, and North West. Schools in these provinces have to source and buy their own food to make the meals.

Provincial departments using the centralised model advertise for service providers to provide schools with the food items for the daily meals. Provinces that follow this model are Gauteng, KwaZulu-Natal, Limpopo, Mpumalanga, and the Western Cape.

In April this year, nutrition challenges at hundreds of schools across the KwaZulu-Natal made headlines. Some schools hadn’t received their food at all from service providers, while others reported serious shortages, or the poor quality of the food they had been given.

The principal thinks it would be a “disaster” if the centralised model were implemented in the Eastern Cape. “I don’t see how they would transport the [food] to us on time and how we’re going to be able to cook it on time,” she says.

According to Equal Education (EE) researcher Stacey Jacobs, many schools in the Eastern Cape received funding for meals for the second term late due to “administrative blunders”.

Jacobs said that the inadequate budget allocation per learner is a longstanding issue. It was already tabled in a 2017 report by the Legal Resources Centre which also said funding for equipment, gas and firewood, water and cooking necessities needed to be included in the NSNP funding.

“For many of these learners, it is their only guaranteed meal of the day … The NSNP helps mitigate the cognitive, physical and emotional or behavioural consequences of hunger that learners may otherwise experience,” Jacobs said.

Mtima of the Eastern Cape education department told GroundUp that the department is not aware of any formal complaints by schools struggling to implement the approved feeding menu.

Mtima said that each district has nutrition monitors who visit schools and review the portion sizes. He said, “no reports have been escalated to the provincial department indicating a lack of portion sizes nor variety/ balance of the three food groups”.

GroundUp sent questions to the national Department of Basic Education on whether all schools in KwaZulu-Natal and the Eastern Cape have been able to adequately resume the NSNP. Spokesperson Elijah Mhlanga replied: “The DBE does not micromanage the programme to this extent, this kind of information is available at the provincial level”.

Published originally on GroundUp | By Liezl Human