The Iliad goes local

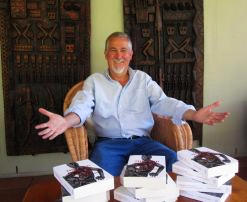

Homer’s Iliad, the well-known Greek poem set in the Trojan War, has been translated into English versions and virtually every language in the world for many centuries, but now a South African professor in classic literature has published the first South African English translation of the epic tale. Prof Richard Whitaker from the School of Languages and Literature […]

Homer’s Iliad, the well-known Greek poem set in the Trojan War, has been translated into English versions and virtually every language in the world for many centuries, but now a South African professor in classic literature has published the first South African English translation of the epic tale.

Prof Richard Whitaker from the School of Languages and Literature at the University of Cape Town spent a decade translating the 3 000-year-old text directly from the ancient Greek, for South African readers.

The project was quite an undertaking, considering that Whitaker didn’t work on it fulltime, but fitted it in between other work commitments.

“I first read The Iliad as a teenager and I loved it then,” says the author who never lost his fascination for the text and has read and taught the work over several decades, both in Greek and English.

(Images: Richard Whitaker)

“I felt that there was a need for a South African English translation. It was an opportunity to reflect South African language, society and culture,” Whitaker says.

In the translation Whitaker uses South African words from all 11 official languages, such as amakhosi (the Zulu and Xhosa word for chiefs and headmen), kgotla (Tswana for community councils), kloof (Afrikaans for valley), sloot (Afrikaans for ditch), assegai or umkhonto (Zulu for spear), lobola (Zulu for dowry) and kraal (Afrikaans for a livestock enclosure or homestead).

Local or international readers who aren’t familiar with all the words can consult the glossary at the end of the book, which explains their meanings and gives the Standard English equivalents.

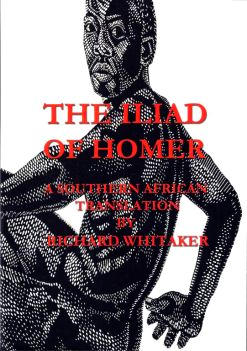

The 528-page translation is self-published and Whitaker hopes that academics, students and ordinary South Africans will enjoy reading it. The Iliad of Homer: A Southern African translation can be ordered here.

Celebrating South African English and culture

Whitaker says there is no reason why classic works such as The Iliad can’t be translated into local English.

“It seemed to me that Southern African English by now had a vocabulary and register of its own that deserved to be reflected in poetic translation,” he says.

“I speak Standard English, but I, like most, also speak a Southern African English that is studded with words from other local languages,” Whitaker said in his introduction to the translated text, referring to popular words such as lekker (Afrikaans for nice) and mugu (an urban African slang word for fool).

“There is a clear indication that South African English is beginning to take itself seriously, is staking a claim to be a distinct variety.”

He says although South African English is often perceived as comic, the language can be used in a serious register. “I want to show that it can be used to translate classics and works of high culture.”

Whitaker’s translation brings the epic tale to life, and highlights the many common aspects between the traditional Greek and African societies that were lost in Euro-centric translations.

The author succeeds in retaining elements of Homer’s world which could resonate with South Africans, such as the payment of bride-price in cattle, and warriors winning praises in combat.

Whereas other translations refer to palaces, princes, royal courts and kings, he believes the society depicted in Homer’s text is a tribal world of small warring communities headed by chiefs.

“In South African English it is less alienating and more accurate,” he says.

Instead of reflecting the world of European elites as earlier translators had done, Whitaker in his version tries to mirror a world closer to home: Achilles, armed with his assegai (a traditional spear), conquers many Trojan impis (the Zulu word for regiments), before he and his men celebrate with a feast of grilled meat which South Africans refer to as a braai.

A relevant teaching tool

He hopes that the translation will nurture a love for the classics, and help students gain a better understanding of the poem.

“I am interested to see how students respond,” he says. “I hope it will intrigue and delight them.”

Whitaker has been invited to teach his translation of The Iliad at the Eastern Cape’s Rhodes University next year.

The South African English version has received international acclaim, and various publications such as the Wall Street Journal, Daily Telegraph, the Middle East North Africa Financial Network and the Greek World Reporter have highly recommended Whitaker’s translation.

“What really pleased me is that overseas people are intrigued by the translation.”

By: Wilma den Hartigh

Source: www.mediaclubsouthafrica.com