South Africa’s Nat Nakasa Goes Home…

Nat Nakasa finally started his journey home today, fifty years after he didn’t want to leave. At a church in the north of Manhattan, not far from where Nakasa jumped out of a seventh-floor window of a building near Central Park in 1965, a service was held to mark the beginning of the repatriation of […]

Nat Nakasa finally started his journey home today, fifty years after he didn’t want to leave.

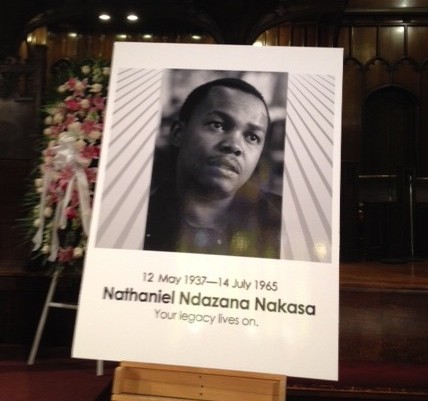

At a church in the north of Manhattan, not far from where Nakasa jumped out of a seventh-floor window of a building near Central Park in 1965, a service was held to mark the beginning of the repatriation of Nakasa’s body to KwaZulu-Natal. Finally, he can be laid to rest in the country he was exiled from and always longed for, South Africa. He would have been 78.

The story of Nat Nakasa might not be that well known today – his was a short life a long time ago, after all – but there are many who remember him as a well-known author, a talented journalist, an exile, and finally an icon.

The story of Nat Nakasa might not be that well known today – his was a short life a long time ago, after all – but there are many who remember him as a well-known author, a talented journalist, an exile, and finally an icon.

He wrote short stories and was the first black journalist to work for the Rand Daily Mail in Johannesburg, giving an inside view of the townships that white readers never would have seen.

When he was awarded a Nieman Fellowship to study at Harvard in 1964, the government denied him a passport but let him have an exit permit, a one-way ticket out. His last column for the RDM, an eerie premonition of the loneliness to come, he titled, ‘A Native from Nowhere.’

“If I shall leave this country and decide not to come back,” he wrote there, “it will be because of a desire to avoid perishing in my own bitterness – a bitterness born of being reduced to a second-class citizen.”

How easy it would be, he said in words almost painful to read, to give up his calling to write. Then he could take up a job for some “madam” in the northern suburbs, who would give him a pair of ill-fitting kitchen-boy pants to wear, and he would get to walk the fox terrier in the white neighbourhoods where no one would know him.

To take the exit permit from South Africa meant not coming home. “This is the unholy possibility which will be driving me slowly around the bend from now on,” he wrote.

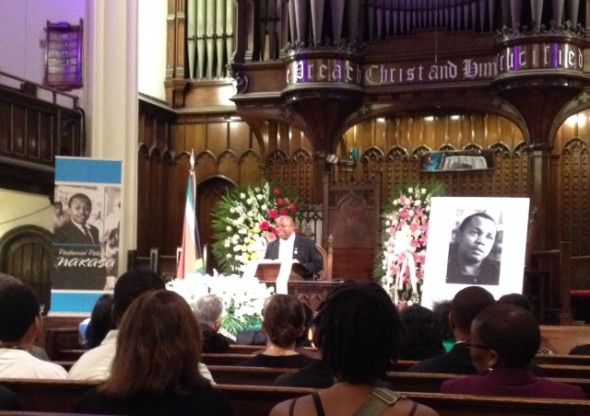

Because his body couldn’t be taken home to be buried, artists like Miriam Makeba, Hugh Masekela and the photographer Peter Magubane collected funds to have him buried in New York. Since 1994, attempts to bring his body home have met bureaucratic and other hurdles, until now. His body was exhumed on Friday, and after the service at the Broadway Presbyterian Church today, he will begin his journey to Chesterville outside Durban to finally be laid to rest.

“His homecoming is the restoration of his citizenship and dignity as a human being,” the minister of culture, Ntathi Mthethwa, said last week.

Nathaniel Ndazana Nakasa, one of five children, started his career at the Natal Sun before moving to work at Drum magazine in Johannesburg. Allister Sparks hired him as the Rand Daily Mail’s first black columnist in 1964.

That he had a sense of humour in the face of everything terrible that he was witness to is undeniable. The writer Can Themba recalled after Nakasa’s death how he had arrived in Johannesburg: “He came, I remember, in the morning with a suitcase and a tennis racket – ye gods, a tennis racket!”

One of the speakers in the New York church recalled that Nakasa and his flatmate in Johannesburg had once placed an ad for a maid, but specified that she had to be white. He dated white women and loved the leafy white suburbs.

“He was a rainbow man before the rainbow nation existed,” said his sister, Gladys Maphumulo, in an interview last week.

After the massacre at Sharpeville in 1961, Nakasa wrote an article for the Times describing the pass laws and the iniquities of apartheid, such as signs outside government buildings saying “Dogs and Natives Not Allowed.” His articles, those windows into South Africa’s black heart, kept coming.

As the government started clamping down on the African National Congress and dissent, it was clear Nakasa’s days of freedom were numbered. Only many years later did a police report surface that showed Nakasa was for a long time under surveillance.

“He is known everywhere as an enemy of the ruling government,” the report said.

If he didn’t take the one-way ticket out, he would probably have been banned. So, damned if he stayed in South Africa, damned if he left.

He did not like New York and moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts, visiting New York occasionally to interview Makeba for a proposed biography and to write about Harlem for the Times. The racism he met in America was probably a shock for him.

“It didn’t take long for Mr. Nakasa’s dream of freedom in America to be shattered by reality, especially during a reporting trip to Alabama for The Times Magazine,” according to a story in The New York Times last week.

“‘There were moments when I wanted to bow to a tenant farmer in Alabama,’” he said, according to Kathleen Conwell (a friend of his at the time), ‘because I understood the miracle of his survival. They took away his identity and yet he has survived.’”

It did not take more than ten months for him to hit rock bottom. I quote the Times: “Ryan Brown, who studied Mr. Nakasa’s life while on a Fulbright scholarship, explained that Mr. Nakasa had learned to cope with South Africa’s abnormalities, and how they even helped establish his identity as a writer. But he had no outlet to deal with the racism that confronted him in America, and it confounded him.

“He found little respite in the classroom, writing in his final Nieman report that ‘the racial problem in the world is one that has emotional and personal rather than intellectual implications.’ Mr. Nakasa grew increasingly homesick, with his banishment from South Africa troubling him more as time passed, the Nieman fellow and newspaperman Ray Jenkins wrote in an unpublished essay.”

The author Joseph Lelyveld, who was a reporter at the Times back then, wrote after Nakasa’s death: “How this man, who was thought of as unaffected and self-contained, finally lost his battle against bitterness in an alien city is something that no one here who really knew him pretends to understand.”

The literary magazine Nakasa founded in 1963 and edited, The Classic, one of Africa’s first literary publications to feature mostly black writing, with contributors like Can Themba and Es’kia Mphahlele, published tributes to Nakasa.

“We have paid again, let us make no mistake,” wrote Athol Fugard. “This was another installment in the terrible price, and South Africa – that profligate spender of human lives – has paid it.”

At the ceremony in New York, the culture minister Nathi Mthethwa delivered a moving speech about Nakasa. He also recalled another black South African, one probably less remembered even than Nakasa, Pixley ka Isaka Seme, who delivered an award-winning speech, The Regeneration of Africa, to Columbia University in New York in 1906. The university, it so happened, was barely a five-minute walk from the service for Nakasa, its buildings in sight as Nakasa’s coffin, covered in a South African flag he never knew, was carried out of the church.

In his last column for the Rand Daily Mail, Nakasa mused for a moment on what his future outside South Africa could bring. Maybe he would take up a new nationality. What should it be? If he became Cuban – at the time countless anti-Castro Cubans were leaving their country – he could get into the United States easily. If he became Israeli, he couldn’t go to conferences in Cairo. Egyptian? No, he had too many friends who were Jewish. Ah, Scandinavian, he thought. “A black Viking. Imagine it!” (One can imagine the impish grin on his face as he wrote those parting words.)

Nadine Gordimer, who died recently and did not get to see Nakasa’s body returned to South Africa, wrote about him at the time of his death.

“The truth is that he was a new kind of man in South Africa, he accepted without question and with easy dignity and natural pride his Africanness, and he took equally for granted that his identity as a man among men, a human among fellow humans, could not be legislated out of existence, even by all the apartheid laws in the statute book, or all the racial prejudice in this country. He did not calculate the population as sixteen millions or four millions, but as twenty. He belonged not between two worlds, but to both. And in him, one could see the hope of one world. He has left that hope behind; there will be others to take it up.”

“Nat is gone forever,” she wrote. “But he was the beginning, not the end of something.”