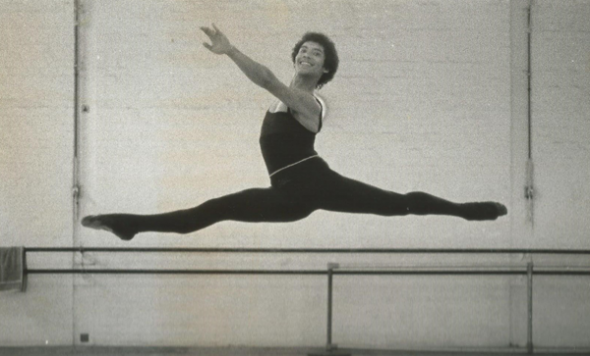

South African Dancers rally to support Christopher Kindo

South Africa’s dance community has come together to support prize-winning Cape Town choreographer and dancer Christopher Kindo who is battling cancer. Kindo has moved back onto the Simonstown property from which he was evicted as a child. Born in 1955, he grew up in Simonstown but his family was moved to Ocean View under the […]

South Africa’s dance community has come together to support prize-winning Cape Town choreographer and dancer Christopher Kindo who is battling cancer.

Kindo has moved back onto the Simonstown property from which he was evicted as a child.

Born in 1955, he grew up in Simonstown but his family was moved to Ocean View under the Group Areas Act and their family home demolished. They got their land back through restitution in 2003 and Kindo’s brother Percy rebuilt their home. Now, after many years travelling the world, Kindo, who has been diagnosed with oesophagal cancer, has joined his brother and sister-in-law Mary in the family home.

Kindo started dancing at the age of nine. “It was a long time ago when we didn’t have TV, so we were always playing and dancing in the street or on the beach. A youth centre was started here in Simonstown and because some of us were always dancing, they got in a ballet teacher and that’s how my interest in ballet started.”

Straight after high school he joined the UCT Ballet School and studied for the three-year Performer’s Diploma in ballet. As a dancer who was classified coloured, this was difficult.

“First of all to even go to UCT we needed a permit, we were not just allowed. We couldn’t afford it, so we needed a bursary which we had to pay back. So it was very problematic.”

After three years some white students got work at once with the Cape Performing Arts Board (Capab) but not Kindo. “So I might have got the award for the best student in my third year, but I couldn’t join the company, because I was not white.”

He wrote to the government in protest. But at the same time he was offered a scholarship with the Boston Ballet Company.

At first, he says, he hesitated. He wanted to be Capab’s first coloured dancer.

But when nine months passed without any definite, positive answer from the government, he decided to leave South Africa and to join the Boston Ballet.

Not being able to dance in his own home country was a blow. “I understood the law and the government and all of that, I understood how it was. But I think it was grossly unfair.”

He stayed only one year in Boston. Although the ballet company offered him a contract, he decided to come back to Cape Town in 1980.

During his absence things had changed a little in South Africa. ”We were lucky. The mixing always started in the arts first.”

Theatres had been desegregated and Capab was now allowed to offer him a contract. But at first he refused it. Instead, he became a founder of Jazzart – the first contemporary dance company in the country. Now he could really start his career as a choreographer, switching from jazz to classical ballet and finally accepting work with Capab.

“As a person of colour you had to work twice as hard, which I did, to prove that I was good enough to get into Capab.”

“Because I opened my mouth so wide in the press, I became the first person of colour to be in the Company. I said one day I want to be on that stage and I did, as the first person of colour, and as the principal dancer.”

“It was not just me, there were other people of colour who were also accepted into the company and I was quite proud about that.”

A lot of people thought he was foolish to return from America to a life under apartheid, but he says: “I wouldn’t have been the same artist if I had not stayed here. Africa is home, it is where I feel most comfortable. I am an African artist even though I pursued international standards. I am African inspired.”

He felt it was of great importance to be in South Africa, because “If I had to be part of the struggle and part of the fighting ahead, I had to do it.”

After that, numerous successes followed. According to Adele Blank, a choreographer and Kindo’s close friend, “He put his mark on South African dance.”

Early this year Kindo was to have gone to work with a dance company in Durban. But he first had a medical check up and suddenly his life changed completely.

“I was so excited and it was two days before I had to go that I went for the check up. Everything went really fast, the next minute I was in hospital. I had to cancel Durban. It is only now in the last couple of weeks that I am finally focusing, after all the chemo and radiotherapy.”

At first, he says, he went into denial, but he slowly came to accept the diagnosis.

“I went into denial straight away. But at the same time … realistic. Okay, this is happening to me. But I am not going to break down, I accept it. Whatever happens, happens.”

“I didn’t have time to get depressed, I didn’t even have time to cry I think I only cried once when my sister-in-law told me that they wanted me to come and stay here because I was most worried about how I was going to afford to live. If I am not working, how I am going to afford to live? The medicine is very expensive, it is like paying rent.”

Blank contacted dance teacher Di Fincham, who put the word out in the dance community and the fund-raising started, with help from consultant Jennifer van Papendorp.

Choreographer Alfred Hinkel dedicated funds from a special performance by his group, Garage, of “The Rust Coloured Skirt” and this plus other donations brought in nearly R100,000.

“Everybody responded all over the world,” said Papendorp. “It was amazing how generous people were.”

Kindo was touched by all this commitment, “It brought tears to my eyes”, he says. “I didn’t cry a lot but that was one of the times I cried.”

Money has also been raised through Dance for a Cure.

But Kindo’s financial situation is still uncertain. “I don’t know how long it will last. I am going to be in trouble one day, it depends how long I live.”

It never crossed his mind to give up.

Hard work has always got him out of difficulty, he says.

“It got me out of a situation, it got me to travel. I cannot imagine what I would have been if I hadn’t pursued dancing. And whatever disappointment I had dancing made me work harder. I achieved everything I wanted to.

“I can’t dance or teach at the moment, but I am hoping to, don’t worry!”

Source: http://groundup.org.za/

The text of this article and its photograph(s) are licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.