South Africa donates cast of crucial fossil discovery to Museum für Naturkunde

Working together to discover our history: South Africa donates cast of crucial fossil discovery to Museum für Naturkunde In 2008, renowned South African paleoanthropologist Lee Berger and his young son Matthew were walking through what they suspected to be a fossil-rich area in the Cradle of Humankind World Heritage Site (COH WHS) in South Africa. While […]

Working together to discover our history: South Africa donates cast of crucial fossil discovery to Museum für Naturkunde

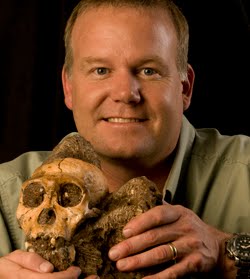

In 2008, renowned South African paleoanthropologist Lee Berger and his young son Matthew were walking through what they suspected to be a fossil-rich area in the Cradle of Humankind World Heritage Site (COH WHS) in South Africa. While Berger was talking to colleague Dr Job Kibii, his son wandered off after their dog, and brought Berger running with the words: “Dad, I found a fossil!”

That fossil was the clavical bone of an early hominid, and is part of the now famous Australopithecus sediba fossils, which have momentously impacted what we know and how we think about the early development of humankind.

In the spirit of collaborative scientific investigation and a desire to share such treasures with the world, the COH WHS, in conjunction with the Institute of Human Evolution at the University of the Witwatersrand, and on behalf of the people and scientists of South Africa, donated a full Au. sediba cast to the Museum für Naturkunde – the renowned Natural History Museum in Berlin, Germany – on 12 March 2012 at a special handover event.

This is part of a series of donations of the cast by the Institute to scientific institutions around the world. Berger and the COH WHS Management authority believe that palaeontology’s greatest challenge is sharing the precious information discovered with the greater community and the world at large – and they hope to change that.

The fossils consist of the remains of two individuals – a juvenile male and an adult female, possibly mother and son. 1.977 million years ago, they fell into a cave and have been so well preserved as to allow researchers, with the help of incredible modern technology, to be able to tell a significant amount about them.

What is extraordinary about the fossils is that they display a curious mixture of characteristics – a blend of earlier and more recent species. The ankle bones of sediba, for example, are made up of an unusual combination of features. While the ankle itself is similar to that of a modern human with features suited to walking and running upright, the

foot is decidedly primitive and ape-like, with a small heel specially adapted for climbing trees. Scientists studying the bones have noted that no other ankle has ever been discovered with so many advanced and primitive features in one bone.

Perhaps even more extraordinary is what scientific analysis of the sediba brain has brought to light. It was previously thought that our ancestors had smaller brains, and that, as they evolved, the size of their brains increased in order to facilitate higher intellectual function.

However, the juvenile male’s brain was mapped using sophisticated scan technology from the pattern imprinted on the inside of his skull. What the scan showed was that Au. sediba had a primitive small-sized brain, but higher organisational functionality – again, a combination of earlier and newer species characteristics. This suggests that the human brain reorganised before it grew in size – a discovery which significantly alters our previous understanding of the manner in which evolution took place.

This has lead Berger and his team to suggest that the species is a transitional one, and perhaps a more likely candidate ancestor for our genus Homo than previous discoveries such as Homo habilis. It is possible that Au.sediba is the ancestor of Homo erectus, commonly believed to be our direct ancestor. This groundbreakingly controversial suggestion has been met by more than one raised scientific eyebrow and prompted much debate.

However, Berger is confident that the more we study the fossils and the more we engage in collaborative scientific investigation, the more we will discover about the sediba species and how and where they fit into the evolutionary tree.

The fossils dealt with in the COH WHS are unique national and world treasures and need to be protected and preserved – but at the same time, it is vital that they are shared with the world. If we have the ability to make casts, why should we not ensure that every institute and museum in the world receives a replica of these famous and invaluable fossils, thereby sharing, protecting and presenting our country’s heritage?

Berger’s philosophy is to encourage research and share the resultant discoveries with the world’s population, allowing people to marvel at these discoveries, to look at them and think about them and reflect on what they tell us about our common ancestry.

CEO of the COH WHS Dawn Robertson is proud to have handed over a cast of the fossil, to be sharing one of the most significant paleoanthropological discoveries ever made with the world. “We are very pleased to be giving Au. sediba to the Museum für Naturkunde,” she said. “In the scientific world, discoveries like this have, in the past, been closely guarded and reluctantly shared (if at all). But we hope to change that. What these fossils show us is that we all evolved from a common ancestor, so it only makes sense that we marvel in these discoveries together, celebrating our shared history and the incredible modern technology and scientific brains that allow us to uncover the mysteries of our past.”