SA’s Great Escape veteran dies

He survived being shot down over France, internment in a Nazi prison camp, escape, recapture, Hitler’s ordered mass murder of his comrades, the Long March to escape the advancing Soviet army – and a freak tsunami back home. Flight Lieutenant Les Brodrick, the last South African to make the legendary Great Escape of the Second […]

He survived being shot down over France, internment in a Nazi prison camp, escape, recapture, Hitler’s ordered mass murder of his comrades, the Long March to escape the advancing Soviet army – and a freak tsunami back home. Flight Lieutenant Les Brodrick, the last South African to make the legendary Great Escape of the Second World War, its “forgotten hero”, died peacefully in KwaZulu-Natal on 8 April. He was 91.

On the night of 24 March 1944, 76 British officers imprisoned at the Nazi camp Stalag Luft III crawled to freedom through a 102-metre tunnel secretly excavated for nearly a year, over eight metres underground. On a moonless night during the coldest German winter in 30 years, Brodrick was the 52nd prisoner of war to emerge and scamper through the snow to hide in the nearby forest. The breakout was made famous by the classic 1953 film The Great Escape, starring Steve McQueen.

Brodrick was born in south London on 19 May 1921. After the war he and his family emigrated to today’s KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa, where he lived, working as an English teacher, for almost 60 years.

At the age of 22 Brodrick was a pilot for the British Royal Air Force (RAF), running bombing raids over Germany and occupied Europe. In April 1943 his Lancaster bomber was hit by anti-aircraft fire over Stuttgart and, his plane limping back to the UK, hit again over occupied France. The plane crash-landed into a field near Amiens, killing four of the seven-man crew.

Air officers’ prison camp

Brodrick was quickly captured and taken to Stalag Luft III prison camp in the German province of Lower Silesia, today part of southeastern Poland. There he soon became deeply involved in an ambitious, long-term escape project organised by another South African, the heroic but tragic RAF Squadron Leader Roger Bushell.

Brodrick was imprisoned in a smaller compound of the larger prison camp, built specifically for British airforce officers. It also held captured airmen from Australia, Canada, Norway, Sweden, Greece, Poland, France, Belgium, Czechoslovakia, New Zealand – and South Africa. In its entirety, the vast camp covered 24 hectares and kept nearly 11 000 prisoners. And it was designed to keep those prisoners inside.

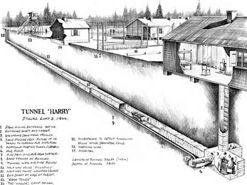

Stalag Luft III was intentionally built on unstable, sandy soil difficult to tunnel through without the risk of collapse. Tunnelling was one of the few successful ways to escape prisoner-of-war camps, to get under the machine-gun watchtowers, electric fences, barbed wire and patrolling sentries. And a tunnel could free far more men than a dangerous dash through a prison fence.

Useful too for preventing escape was the sand’s bright yellow colour, which made secretly disposing excavated tunnel soil difficult on the asphalt grey of the prison grounds. The Germans also embedded microphones into the ground to pick up any sound of digging. At 8.5 metres underground, the height of 5 tall men, the Great Escape tunnel was dug deep to escape detection.

Soon after he arrived in the camp, Brodrick was recruited into the north compound’s escape committee, known in prisoner code as X-Committee. The secret group was put together by Roger Bushell who, as its mastermind, was given the code name Big X.

Soon after he arrived in the camp, Brodrick was recruited into the north compound’s escape committee, known in prisoner code as X-Committee. The secret group was put together by Roger Bushell who, as its mastermind, was given the code name Big X.

The escape expert

Bushell, born in Springs east of Johannesburg and educated in the UK, was already a veteran of two bold escapes from Nazi camps. One required hiding in a goat pen, prostrate in the animal’s faeces, waiting for guards to move on. In the second he sawed through the boards of a moving prison train to drop between churning wheels onto the tracks below.

Bushell was recaptured after both escapes. His second saw him fall into the hands of the notorious Gestapo Nazi secret police, who in all likelihood tortured him, although he would never talk about it. Most accounts say he arrived at Stalag Luft III with a deep hatred of all Germans, and determined to make one, final and grand escape.

It’s also said that around the time he began planning the Great Escape, Bushell received a letter from his fiancée telling him she was to marry another man. He’d been imprisoned or on the run for three years.

In the German spring of 1943 Bushell put together an ambitious plan to dig not one, but three tunnels under and out of Stalag. His thinking was that, if one were discovered, the Nazi guards would find it inconceivable that more tunnels were still in progress. That would give them time to dig at least one robustly fortified and engineered tunnel – large and well-planned enough to allow more than 200 men to escape.

In the British way, the tunnels were given the code names Tom, Dick and Harry.

According to Australian journalist Paul Brickhill, a fellow prisoner who wrote a book about the escape after the war, when Bushell announced his plan to the X-Committee they were shocked at its fearless extravagance. Bushell apparently roused them with these words:

“Everyone here in this room is living on borrowed time. By rights we should all be dead.

“In north compound we are concentrating our efforts on completing and escaping through one master tunnel. No private-enterprise tunnels allowed. Three bloody deep, bloody long tunnels will be dug – Tom, Dick and Harry. One will succeed.”

Tom, Dick and Harry

As the plans progressed, Les Brodrick’s responsibility was as a “trapfuhrer”, guarding the secret entrance to Dick. Access to the tunnel was hidden under a drain in a washroom. Brodrick would open it for the diggers to enter, close it and then keep watch for guards as his comrades tunnelled underground.

It was perhaps because it was an officers-only camp, filled with men with the benefit of an education, that the Great Escape’s tunnelling plans were both ambitious and ingenious. To prevent the easy collapse of the camp’s sandy yellow soil, wooden boards supporting prisoners’ bunk-bed mattresses were secretly filched to shore up the tunnel walls. Before the operation, every bed in the compound had 20 boards. At its end, they had an average of eight, and 90 double bunk-beds had vanished.

The X-Committee came up with inventive ways of disposing of the yellow tunnel soil in the grounds of the camp, raking it to gardens and dumping it in the basement of the compound’s theatre. Prisoners would shuffle around with sand stuffed in long thin bags in their trousers, slowly dribbling the load onto the ground as they walked with a gait that gave them the nickname “penguins”.

To get air into the tunnels, ventilation ducts were snaked together using empty cans of Klim, a milk powder provided by the Red Cross. The cans’ metal was also used to make small digging tools and candle holders. Underground candles were made by stealthily scooping fat off soup served in the mess hall, saving it in small tins, and lighting it with wicks made from the threads of old clothes.

Tunnel Tom was the first to go. Bushell decided to give the tunnel priority, but the extra activity triggered the underground microphones. The camp was searched, and in September 1943 the entrance to Tom was discovered and destroyed with explosives. It was the 98th escape tunnel found in the camp since the beginning of the war.

The Germans were euphoric with their success, and their vigilance dropped. Bushell had been right: a German-speaking prisoner overheard guards saying that if such an enormous and well-constructed tunnel had been discovered and destroyed, there couldn’t possibly be another underway.

Soon after, construction of Brodrick’s tunnel Dick was stopped when the Germans began building a new prison compound over its planned exit. But the tunnel wasn’t abandoned: it continued to be a useful hiding place for wooden bed-boards and other filched material needed for the ongoing construction of the remaining tunnel, Harry.

In March 1944 Harry was complete, and still undiscovered. It was an amazing piece of engineering for an entirely secret project. The tunnel was 102 metres long, dug 8.5 metres underground, and had electric light, a ventilation system and a railway track with carts for removing the soil.

After the escape the Germans inventoried camp equipment and, from the amount of material missing, discovered the huge scale of the tunnel-construction project. Other than the 4 000 bed-boards and 90 bunk beds, the escape crew had stolen 192 bed covers, 161 pillow cases, 62 tables, 34 chairs, 76 benches, 1 212 bed bolsters, 1 370 beading battens, 1 219 knives, 478 spoons, 582 forks, 69 lamps, 246 water cans, 30 spades, 300 metres of electric wire, 180 metres of rope, 3 424 towels, 1 700 blankets – and more than 1 400 Klim cans.

The escape begins – slowly

After waiting for a moonless night to ensure the cover of darkness, on 24 March 1944 the prisoners began to assemble in Hut 104, where the entrance to Harry was hidden under a moveable stove. Experienced escapers and those fluent in German were given places at the top of the escape roster. The rest drew lots. Bushell was given third place; Brodrick drew 52nd.

They soon ran into trouble. On an exceptionally cold winter night with the ground covered in 15 centimetres of snow, the escape hatch was frozen shut. It was worked open and prisoner Johnny Bull broke through to the surface, only to discover that the exit was in the middle of the cleared perimeter patrolled by sentries, five metres short of the line of fir trees planned as cover. The prisoners would have to crawl through thick snow, only metres from a watchtower, to reach the protection of the forest.

But the escape had to go ahead. Not only would another wait for a moonless night increase the chances of discovery, but all the prisoners’ meticulously forged travel documents were stamped with that day’s date.

The escape began, but at a much slower rate than planned. First out was Harry Marshall, followed by Ernst Valenta, and then Bushell. Instead of the man a minute that could easily have freed all 200, the escape crawled to 12 men out every hour.

From the night of the 24th to the morning of the 25th, the escape went on. Les Brodrick was the 52nd to emerge. After making it into the woods, he teamed up with Canadian Henry Birkland and British officer Denys Street, the three of them planning to rough it through the frigid forest southwards into Czechoslovakia and freedom.

Back at the tunnel, the 77th man stumbled out of the hole into the path of a patrolling sentry. The whistle sounded, the alarm went up, and the Great Escape was over.

Capture and reprisals

Of the 76 men who escaped, only three made it home. The other 73 were quickly rounded up, many at the local railway station where their clear unfamiliarity with their surroundings made them stand out to watchful Germans.

Bushell and Bernard Scheidhauer, the fourth man out, were the first to be captured. They’d managed to board a train and had reached as far as Saarbrucken in eastern Germany, tantalisingly close to the French border, when police inspected their papers and discovered they were forged.

Bushell fell back into Gestapo hands. On 29 March 1944 he and and Scheidhauer were put in a Gestapo car, to be taken to a handover to the “relevant authorities”. Some 40 kilometres into the trip the car stopped, the prisoners were told to relieve themselves and, while the stood at the side of the road with their backs turned to their captors, shot in the neck. Three days after his Great Escape, Bushell was dead. He was 34.

Brodrick, meanwhile, had made it some way through the forest with Birkland and Street. The three came to a small cottage and, hoping for some respite from roughing it, knocked on the door. Inside were two men. In their broken German the Brodrick and his friends tried, later reports said, to “spin a yarn” to the men – try to explain why they, three strangers, were in the forest in the middle of a winter night not far from a prison-of-war camp. The men in the cottage were German soldiers, and Brodrick and his companions were arrested.

Brodrick was taken to Gestapo headquarters in Gorlitz for interrogation, and then sent back to Stalag Lutz III.

When he returned, Brodrick learned that 50 of the 76 men he had joined in the Great Escape had been murdered by the Gestapo. Bushell was dead, as too were Brodrick’s companions Birkland and Street.

The Great Escape had a strong element of good British fun. It was daring, it was mischievous, its code names were corny, and there was a sense that other than the chance of being shot during escape, there was no desperate danger. Germany was a signatory to the Geneva Convention, which outlawed the execution of prisoners of war, escaped or not.

But Adolf Hitler had other ideas. Enraged at the audacity of the escape, Hitler ordered that all 73 captured men be executed. His advisors were alarmed, and talked him down – to 50.

In the film The Great Escape, the 50 are herded onto a hilltop and executed en masse. In reality the Gestapo, knowing they were committing war crimes, executed them in twos and threes, driving them to a remote location, getting them out of the vehicle, and then shooting them from behind to create the pretext that they were trying to escape.

Many years later, Brodrick was asked if the Great Escape was worth it. “I suppose we did cause a certain amount of destruction,” he said. “But was it worth it? No, with 50 men dead, I don’t think so.”

Three other South Africans were among the 50 murdered: Clement McGarr and Rupert Stevens, both 25, and 24-year-Johannes Gouws, a Free State farmer’s son who just wanted to fly. After the war, the murder was one of the crimes tried at Nuremberg.

The Long March and home

Brodrick remained imprisoned at Stalag Luft III until just before the end of the war. As the Soviet army advanced from the east, Hitler ordered that all prisoner of war camps be emptied and their inmates force-marched westwards to Germany. Brodrick joined 80 000 other prisoners in the notorious Long March through a bitter winter from January to April 1945. It was later estimated that over 8 000 died.

On 2 May 1945 Brodrick was among prisoners liberated by the British at Lubeck in northern Germany, and was flown back to the UK in a Lancaster bomber from his old squadron.

Back home with his family, he became a teacher in Canvey ¬Island, Essex. In 1953 the region was hit by a massive tsunami caused by freak weather conditions, with Canvey Island bearing the brunt. The family decided to leave, and in 1956 emigrated to Amanzimtoti in KwaZulu-Natal, soon moving to Scottburgh nearby. Brodrick became a South African, living here for almost 60 years.

After his death his cousin John Fishlock told British newspapers Brodrick had become a forgotten hero because he moved to South Africa. “He was a remarkable man who deserves recognition,” he said. “He never knew why he was spared the firing squad – it was simply luck of the draw. His son Duke was just six months old at the time and he used to say that Hitler must have heard about that and spared him.”

Only two survivors of the Great Escape remain: 93-year-old Dick Churchill, who lives in the UK, and 99-year-old Paul Royle of Perth, Australia.

Les Brodrick leaves behind his wife, Theresa, 92, his sons Roy, 67, and Duke, 70, and two grandchildren.

By: Mary Alexander

Source: www.mediaclubsouthafrica.com