Old Fourlegs – a fishy tale

Had it not been for the passion of a self-trained South African naturalist, the discovery of a living specimen of the rare coelacanth around this time in 1938 may never have happened. Eastern Cape native Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer originally trained as a nurse. Although her wish was to work in a museum, there were few opportunities […]

Had it not been for the passion of a self-trained South African naturalist, the discovery of a living specimen of the rare coelacanth around this time in 1938 may never have happened.

Had it not been for the passion of a self-trained South African naturalist, the discovery of a living specimen of the rare coelacanth around this time in 1938 may never have happened.

Eastern Cape native Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer originally trained as a nurse. Although her wish was to work in a museum, there were few opportunities at the time.

Her wish did come true – in 1931, without any formal training, she landed the position of curator of the East London Museum, established a decade before and still in existence today. The museum had just moved to new premises, and Courtenay-Latimer was 24 at the time.

Her passion for her work was boundless, and her main interest was birds. In her desire to gather unusual specimens for the museum, she did much of the collecting herself.

Reports say that she donated her great-aunt Lavinia’s dodo egg to the museum – apparently the only dodo egg in existence today, although this is a debatable issue as DNA tests have not been allowed.

Reports say that she donated her great-aunt Lavinia’s dodo egg to the museum – apparently the only dodo egg in existence today, although this is a debatable issue as DNA tests have not been allowed.

In 1935 she and a colleague excavated the almost complete fossil skeleton of the mammal-like reptile Kannemeyeria simocephalus from a site near Tarkastad in the Eastern Cape. This species is said to be the standard against which other similar animals from the Middle Triassic period is compared.

Courtenay-Latimer also sent out a request to local fisherman to alert her if they caught anything out of the ordinary.

It was this foresight that led to the identification of a fish that had only ever been seen as a fossil and was thought to have died out about 70-million years ago. On 22 December 1938 Courtenay-Latimer received a call from Hendrik Goosen, the skipper of the fishing trawler Nerine, which had netted a catch just off the Eastern Cape’s Chalumna, or Tyolomnqa River.

According to the South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity (SAIAB, formerly the JLB Smith Institute of Ichthyology), which runs an extensive coelacanth programme, Goosen had caught the fish alive in 70m of water and was conscientious about keeping it intact for scrutiny by the museum. He also described its colour when caught as blue, although this had faded to grey by the time the ship came back to port.

In his diary, Courtenay-Latimer’s father Eric described her wonder and excitement regarding the find. He wrote that although his daughter was busy putting together a fossil collection, she set it aside for the sake of scientific curiosity and went down to the harbour. The 58kg fish she found on the Nerine was unlike anything she had ever read about.

In his diary, Courtenay-Latimer’s father Eric described her wonder and excitement regarding the find. He wrote that although his daughter was busy putting together a fossil collection, she set it aside for the sake of scientific curiosity and went down to the harbour. The 58kg fish she found on the Nerine was unlike anything she had ever read about.

Zoological find of the century

For help with identification, Courtenay-Latimer turned to a friend, chemistry lecturer and fish enthusiast James Leonard Brierley Smith of Rhodes University in Grahamstown.

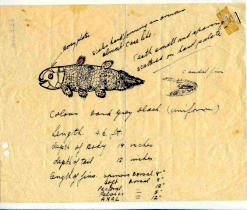

The academic, after whom SAIAB was originally named, was unable to take her call as he was away at the time, but he received Courtenay-Latimer’s subsequent correspondence on his return and looked at her enclosed drawing of the fish, which had by that time been mounted to prevent it from rotting away.

Smith recognised it straight away as a coelacanth but was unable to travel immediately to make a visual identification, a situation that caused him much anguish.

“Fifty million years! It was preposterous that coelacanths had been alive all that time, unknown to modern man,” he later wrote in his book Old Fourlegs: The Story of the Coelacanth.

“Fifty million years! It was preposterous that coelacanths had been alive all that time, unknown to modern man,” he later wrote in his book Old Fourlegs: The Story of the Coelacanth.

When Smith received three scales in the post, his anguish was wiped away. “They leave little doubt about the nature of the fish, but even so my mind still refuses to grasp this tremendous impossibility,” he wrote back to Courtenay-Latimer.

Even so, Smith was determined to see the fish with his own eyes and finally, almost two months after the catch, he and his wife made it to East London.

“Although I had come prepared, that first sight hit me like a white-hot blast and made me feel shaky and queer, my body tingled,” he wrote in Old Fourlegs. “I stood as if stricken to stone. Yes, there was not a shadow of doubt, scale by scale, bone by bone, fin by fin, it was a true coelacanth.”

Smith named the fish Latimeria chalumnae in honour of the young curator and the river near which it was found. When the news broke of the “most important zoological find of the 20th century”, the pair became overnight celebrities.

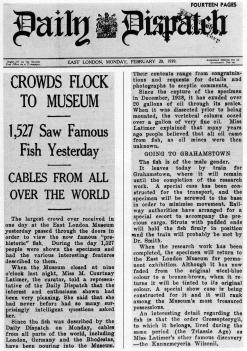

In February 1939 the fish went on display to the public at the museum, attracting 1 527 people, according to the Daily Dispatch. This was the largest crowd that had ever passed through the doors in a single day. That original fish is still in the East London Museum, where it is a popular drawcard.

But to see the stately coelacanth in live action, watch this May 2011 video (WMV, 6.5MB) of specimens near Sodwana Bay in KwaZulu-Natal, showing their vivid blue colour and white spots.

Smith played an important role in organising the search that led to the discovery of a second coelacanth, 14 years later, off the coast of Anjouan Island, part of the Comoros group located in the Indian Ocean between Madagascar and Mozambique. He wanted to capture another fish to scientifically confirm its identity, as the internal organs of the first one had been lost during taxidermy.

When found, it was thought to be another new species and was named Malania anjouanae in honour of the then South African prime minister Daniel Malan. Malan had loaned Smith an air force Dakota so that he could speed to the Comoros and bring the fish home before it decayed – almost causing an international incident with French authorities in the process.

When found, it was thought to be another new species and was named Malania anjouanae in honour of the then South African prime minister Daniel Malan. Malan had loaned Smith an air force Dakota so that he could speed to the Comoros and bring the fish home before it decayed – almost causing an international incident with French authorities in the process.

Courtenay-Latimer, South Africa’s zoological heroine, retired as curator in 1973 and died in 2004 at the age of 97. In 2003 casts of her footprints were placed in Heroes Park in East London, a venue that celebrates prominent people from the Eastern Cape, including Walter Sisulu and Nelson Mandela.

Unchanged for millions of years

The coelacanth is classified as critically endangered by the Red List of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature. While the fossil record has revealed some 80 species of coelacanth, there is just one other living species in the genus Latimeria, the Indonesian coelacanth (L. menadoensis).

The fish is believed to live to a ripe old age, as much as 80 years according to some scientists who have studied growth rings in its ear bones. It’s thought to have developed during the Devonian period about 400-million years ago, and is in much the same shape today as it was then.

Related to lungfishes and tetrapods, or early four-footed animals, the so-called living fossil can grow up to two metres in length and weigh as much as 80 kg.

It has a number of primitive distinguishing features that some scientists feel represent a step in the evolution of fishes into land animals. Its paired fins are fleshy and lobed and are supported by bones. This has given rise to the fish’s nickname – Old Fourlegs. Smith published Old Fourlegs: The Story of the Coelacanth in 1956, a book that was later translated into seven languages, although the American version omitted the nickname in the title. It may be read online at the Open Library.

The dorsal fin also contains hollow spines and it’s this feature that gave the animal its name – from the Latin cœlacanthus, meaning “hollow spine” (Greek, coeliac meaning hollow and acanthos meaning spine). This was bestowed on it in 1839 by palaeontologist Jean Louis Agassiz on examining a fossil.

The coelacanth forages for food at night and hides in caves during the day. Using a special electrosensitive cavity in its snout, known as a rostral organ, the animal can find prey and navigate around obstacles in the dark. Because of the depth at which it usually lives, between 90m and 200m, its eyes are adapted with a tapetum lucidum, a layer of tissue behind the eye that reflects light back through the retina and improves vision in dim light.

Another distinguishing feature is the coelacanth’s hinged mouth, thanks to an intracranial joint that allows the front of the head to lift high and the mouth to open remarkably wide when feeding. The coelacanth’s brain is tiny in relation to its body size and occupies just 1.5% of the brain cavity. In a 40kg specimen, the brain typically weights about three grams – this is the smallest brain to body size ratio observed in a living vertebrate.

Then, on the outside of its body, its keratin-covered scales are tightly bound almost like armour, for protection. They are known as cosmoid scales and are one of the features pointed out by Courtenay-Latimer in her first letter to Smith.

The coelacanth also has a hollow pressurised fluid-filled notochordal canal that runs the length of its body and serves as a backbone. The fish is classified as a vertebrate although it has no vertebrae, but the notochord serves the purpose.

The coelacanth gives birth to live young, called pups. Since the first sighting in 1938, live specimens have been seen in the Comoros, Kenya, Tanzania and Zanzibar, Mozambique, Madagascar, and in South Africa’s iSimangaliso Wetland Park, a world heritage site.

By: Janine Erasmus

Source: www.mediaclubsouthafrica.com