New Movie Revives Interest in a South African in Wartime Europe

On Christmas Day, 1944, a young South African died tragically and far away from home, and despite his incredible achievements, bravery, creativity, not to mention the romance of his life, he still remains largely unknown in the country of his birth. George Steer, in the 35 years he was alive, crammed an exciting, dangerous and astonishing career. He […]

On Christmas Day, 1944, a young South African died tragically and far away from home, and despite his incredible achievements, bravery, creativity, not to mention the romance of his life, he still remains largely unknown in the country of his birth.

George Steer, in the 35 years he was alive, crammed an exciting, dangerous and astonishing career. He has been written about, roads in England and Spain have been named after him, and a new movie is based partly on his character. But it is largely forgotten that he was born and grew up in East London – a South African Englishman, as he once put it – the son of a onetime editor of the Daily Despatch.

While the main character in a new movie “Gernika” is based loosely on Steer – as well as on Ernest Hemingway and the photographer Robert Capa, men Steer probably knew well – the South African could quite easily fill a movie of his own. In his short lifetime, he took part in the Spanish Civil War (on the losing side of the Republicans), gained renown as a wartime journalist, befriended the Ethiopian emperor Haile Selasse, wrote numerous books, most of them about Africa, lost his wife in childbirth while he was rushing across wartime Europe to see her, and then died in 1944 when his jeep overturned in Bengal, where he was working for British intelligence.

While the main character in a new movie “Gernika” is based loosely on Steer – as well as on Ernest Hemingway and the photographer Robert Capa, men Steer probably knew well – the South African could quite easily fill a movie of his own. In his short lifetime, he took part in the Spanish Civil War (on the losing side of the Republicans), gained renown as a wartime journalist, befriended the Ethiopian emperor Haile Selasse, wrote numerous books, most of them about Africa, lost his wife in childbirth while he was rushing across wartime Europe to see her, and then died in 1944 when his jeep overturned in Bengal, where he was working for British intelligence.

Certain episodes in Steer’s life echo those of George Orwell and T.E. Lawrence (better known as Lawrence of Arabia). Orwell also reported on – and sided with – the Republicans in Spain, where their paths obviously crossed, and Orwell even reviewed Steer’s book about the Spanish war, “The Tree of Gernika”. T.E. Lawrence, meanwhile, who fought alongside the Arabs against the Turkish Ottomans, was a compact man like Steer, wrote a famous book about his experiences, as did Steer, and died in a motorbike accident at the age of 46.

A scene from the movie “Gernika”

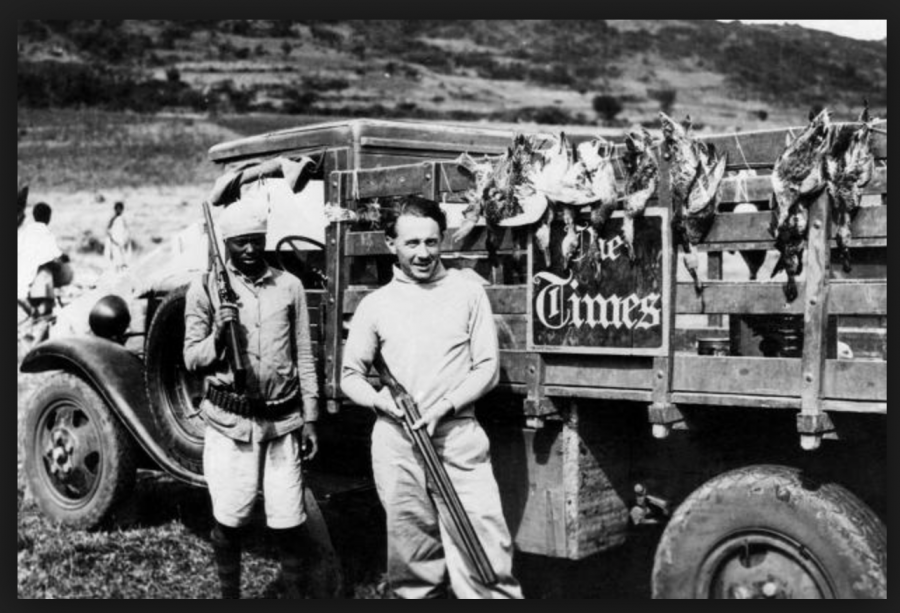

Before going to Spain, Steer covered the Abyssinian War – siding with the locals against the Italians – and during that time befriended Haile Selassie, who later became godfather to Steer’s son. Another well-known author there at the time, Evelyn Waugh, seemed to take a profound dislike to Steer because, it has been suggested, Steer was better educated and a liberal. Later Waugh skewered him in his novel “Scoop”, in the person of Pappenhacker, a reporter for the fictional Twopence newspaper.

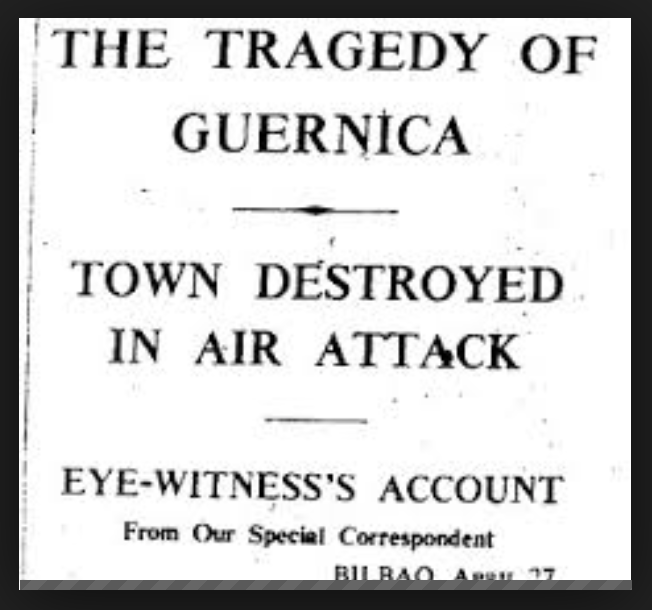

Despite Steer’s full and eventful life – he wrote eight books in the decade before he died – he is perhaps most remembered for his reporting of the German bombing of the Spanish town of Guernica in 1937 – a horrific event that inspired Picasso to create his iconic painting of the same name.

Shortly afterward Steer wrote his best-known book, “The Tree of Gernika”. Hemingway’s war correspondent wife, Martha Gellhorn, was so taken with work that she implored the U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt’s wife, Eleanor, to read it.

“You must read a man named Steer. It is called The Tree of Gernika, and it is about the fight of the Basques – he is the London Times man – and no better book has come out of the war and he says well all the things I tried to say to you all the times I saw you, after Spain. It is beautifully written and true, and few books are like that, and fewer still that deal with war. Please get it.”

Described as “stocky, cocky and physically very fit,” Steer referred to himself as a “South African Englishman”.

A review of Nicholas Rankin’s biography of Steer, who wrote “Telegram from Guernica: The Extraordinary Life of George Steer, War Correspondent”, says of the correspondent that “Despite being foreign-born, he was well connected in Fleet Street, and in 1935 – following a Winchester/Christ Church education – a mixture of nepotism and talent landed him the position of Times correspondent for the Italo-Abyssinian war,”

He joined the Spanish Civil War shortly after leaving Abyssinia, as a freelancer for the Times. By 1937 the war was in its second year, with the right-wing General Francisco Franco, supported by Hitler, rising up against the left-wing Republican government.

Two parts of Spain, the Basque country and Catalonia, sided with the Republicans in return for more autonomy, which made them targets for Franco. On 28 April 1937, two days after the bombing of Guernica, the Times ran Steer’s story and the New York Times put it on the front page.

Steer described in detail how German aircraft poured thousands of bombs on Guernica (the Basques spell it Gernika) and then other planes flew in low to machine-gun people fleeing. Steer’s book “The Tree of Gernika, a Field Study of Modern War” came out in January 1938, right after the Basques had been defeated by Franco.

Steer was clearly biased towards the Basques, but as George Orwell said in his review of the book, you don’t cover war without choosing a side.

In this video, Steer’s biographer Nicholas Rankin reads his famous and chilling report on Guernica:

In Abyssinia Steer met Margarita de Herrero y Hassett, who he later married. While reporting on the Spanish Civil War, Steer heard that Margarita, who was pregnant, was dangerously ill. The Basques laid on a ship to get him to Bayonne and from there to England, but by the time he reached London his wife and child were dead.

Steer was a liberal, who took the side of the Republicans and the Abyssinians, and this eventually put him on the outs with the conservative Times. What he saw in Spain probably brought back memories of the war in Abyssinia, where Italian pilots used yperite (mustard gas) bombs on Abyssinian troops, and then dropped conventional explosives on the Red Cross brigades sent in to help the gas victims. Steer later helped in the restoration of Selassie to the throne in 1941.

During the war he was sent to India to lead a Field Propaganda Unit in Burma. The unit apparently tried to break Japanese morale by loudspeakers with speeches and sentimental music. He was successively promoted to the rank of lieutenant-colonel. He died when a heavily loaded army jeep crashed on the way to a Christmas party in Bengal in 1944.