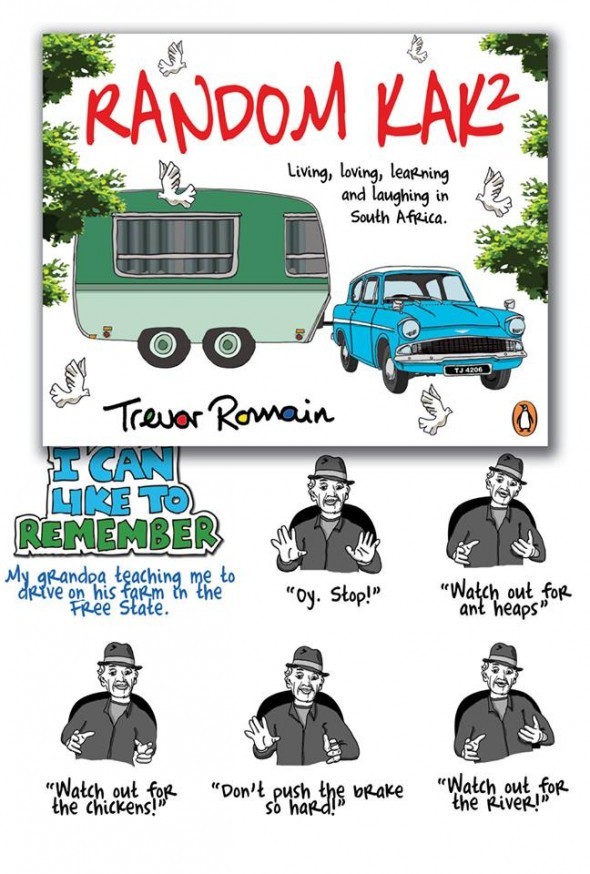

More ‘Random Kak’ from South African expat Trevor Romain

Fans of author, humanitarian, philanthropist – and South African expat – Trevor Romain will be pleased to know that Trevor’s second book in the very popular Random Kak series has gone to print. In a message to SAPeople, Trevor said: “I am happy to announce that my second book in the Random Kak series has gone […]

Fans of author, humanitarian, philanthropist – and South African expat – Trevor Romain will be pleased to know that Trevor’s second book in the very popular Random Kak series has gone to print.

In a message to SAPeople, Trevor said: “I am happy to announce that my second book in the Random Kak series has gone to print. It will be out in South Africa in October from Penguin Books.”

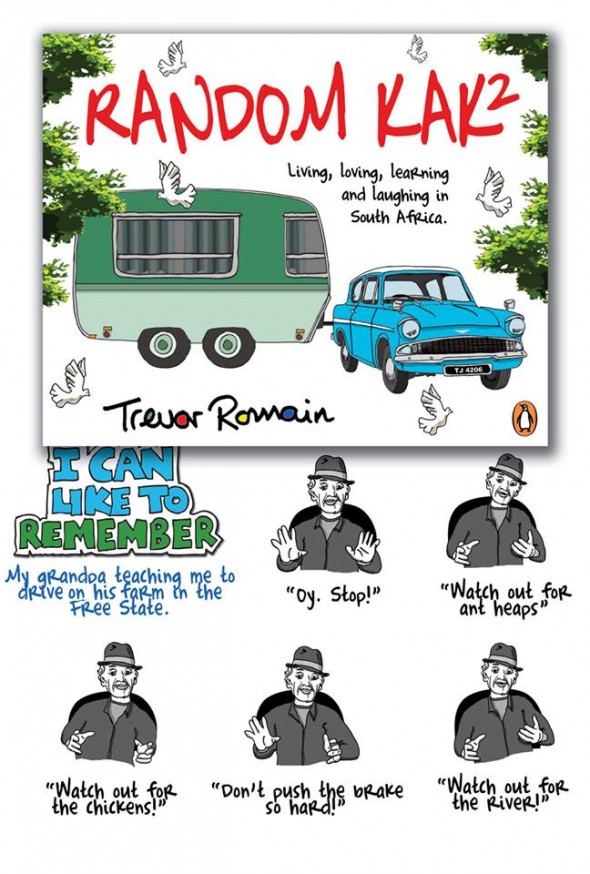

Below is the cover of the new book as well as one page…and the story that inspired that page.

“It’s a bit long so grab some Five Roses and settle in for a break from all the bad news in the world today,” says Trevor!

My Grandpa Teaching Me to Drive on his Farm in the Freestate – by Trevor Romain

“Brakes, Brakes,” he yelled.

Oh my god!

I jammed on the brakes and we came to a screeching, dust-swirling, stop right in front of a huge ant heap.

I got such a fright I almost swerved into the mileie field.

My grandpa leaned over and gently klapped me on the back of my head.

“Avoid ant heaps,” he said. “Now, carry on driving.”

I was about fifteen years old and my grandpa was teaching me to drive on his farm near Vredefort in the Free State. (Don’t ask.) The car was a huge bliksemse gray Chevy with a full seat in the front. It was a tank and I could hardly see over the bloody dashboard.

Every time we went to the farm my grandpa took me driving in that grey bumbershoot of a car. And every time I hit a bump or came too close to an ant heap or was about to run over a chicken he gave me a klap on the back of my head.

“Avoid the chickens,” he said. “Now, carry on driving.”

One time I was distracted by a bunch of Meer cats laughing at me when I drove past them sitting on top of an ant heap that I almost drove into the river.

Klap.

“Avoid the river,” he said. “Now, carry on driving.”

My grandpa was amazing. I often watched him giving the calves their injections. I couldn’t believe how strong he was. He just flipped the little calves over and zip-zip zap-zap he gave them their shots. All the time speaking so nicely and sweetly to them “It’s okay my girlie,” he‘d say to the lowing little calf as he injected her. Then he would carefully massage the spot where he had injected the animal and set her back on her feet waiting patiently as she steadied herself.

A number of years ago, (when I began my stint as a board member and subsequent board president of the American Childhood Cancer Association) I started visiting kids at the cancer hospital in Austin, where I now live. (Some parts of Texas remind me of my grandpa’s farm in the Free State I must say, but that’s another story.)

At that time I was known as the Doctor of Mischief. I spent hours and hours at the hospital driving the kids crazy with jokes and stories and cartoon drawings.

One day I was visiting a young guy named Victor who was about ten years old. He was putting up a hell of a fight after a harrowing bone marrow transplant. We were drawing together in his hospital room when he suddenly turned to me and said, “What’s going to happen to me when I die?”

Jeez, before I could say a word his mom ran over to the bed and said, “You are not going to die dammit! I told you.”

Behind his mother’s back the kid looked at me, shrugged, pulled a tongue and flashed a broad smile. He was a naughty little shit I swear.

A short while later his mom left the room and I said to him. “You know buddy we’re all going to die one day…?”

“I know,” he said, interrupting me. “She thinks I’m stupid. I know what’s going on. Hey do you think there’s… like… a heaven up there?”

“I hope so,” I said, taken aback by his question

“Do you think they give you a map when you get there?” he said.

“Huh?” I said.

“The place must be huge,” he said, “How do you know where to go?”

I laughed so hard I about sprayed the coffee I was drinking out of my nose.

“I’ll tell you what,” I said. “If you die from this disease, while you’re still a kid, ask for my grandpa when you get up there.”

“What do you mean?” he said, laughing.

I told him all about my late grandpa and what a wonderful, caring man he was and hopefully still is. I told him all about my driving on the farm and the ant heaps and how grandpa would klap me upside the head. He laughed at all the stories I told about my grandpa.

“Look for him. He’ll get you checked in and get you a great room,” I said.

“But how will I find him?” he asked. “There must be, like, millions of people up there.”

I thought for a moment and then pictured my grandfather. In my mind I saw his face as clear as daylight.

“Hang on,” I said, and I drew a quick picture of my grandpa in my journal. I tore out the page and gave it to him.

“His name is Teddy Tanchel,” I said. “Memorize that picture.”

He looked at the drawing of my grandpa and said, “He looks real nice.”

“Oh, he is the best,” I said, putting my hand on my heart. “You’ll see. And if there are cars in heaven, he’ll teach you to drive.”

The next time I came to visit Victor the picture of my grandfather was up on the cork pinning-board in his room next to all his get-well cards.

When I teased him, which I often did, he would point to the picture of my grandfather and tell me he was going to tell my grandpa about it, when he saw him, if I didn’t stop teasing him.

I’m very sad to say that cancer won the battle and Victor died about 5 months later.

His mom asked me to deliver the eulogy at his funeral. It was one of the hardest things I have ever done in my life.

I went to the church only to discover that it was an open casket ceremony. I had never seen a child in a coffin before and I did not want to see him like that. I avoided the casket and went into the church.

They wheeled the bloody coffin in to the church and put it next to the pulpit. Open!

The priest delivered his sermon and then called me up to do the eulogy. I did a humorous memorial based on Victor’s wicked sense of humour. I wanted to celebrate his life instead of mourning his death.

We all laughed so hard and I managed not to look at the coffin the whole time.

As I finished my speech I pointed to the coffin and said, “As he was dying, that little boy taught me so much about living…” as I spoke I accidentally glanced at the coffin.

And I’m so glad I did.

Victor was lying there with his hands resting on his chest. He looked so comfortable and at peace. He was dressed in a black tuxedo with a red bow tie. His head bald from the chemotherapy. He had such a sweet, innocent, peaceful look on his face.

In his coffin, surrounding his body, were all his childhood toys. And a sea of flowers. His Lionel train set was in there. Also his baseball glove, hundreds of Lego’s and his blankie from when he was a lightie.

I smiled and mouthed goodbye to him as I walked past the coffin on the way back to my seat.

And that’s when I saw the picture of my grandfather that he was holding in his hand.