Januaries keep Mandela spirit alive in France

Everyone has a memory bank of images: Nelson Mandela, fist clenched, walking to freedom from Victor Verster Prison; the limp and lifeless body of Hector Pieterson being carried by a fellow pupil; the queues of South Africans waiting to vote in 1994. For sports mad South Africans there is the picture of Mandela handing the […]

Everyone has a memory bank of images: Nelson Mandela, fist clenched, walking to freedom from Victor Verster Prison; the limp and lifeless body of Hector Pieterson being carried by a fellow pupil; the queues of South Africans waiting to vote in 1994. For sports mad South Africans there is the picture of Mandela handing the Rugby World Cup trophy to Francois Pienaar.

There is another image from July 2008, less famous but just as moving for Springbok fans. It is of scrumhalf Ricky Januarie diving over the try line in Dunedin, in New Zealand, to give South Africa its first win in the Land of the Big Cloud in 10 years. It was a riotously creative piece of skill that made the stocky scrumhalf from Hopefield, a town on the road between Malmesbury and Vredenburg in Western Cape, a hero to millions of rugby fans.

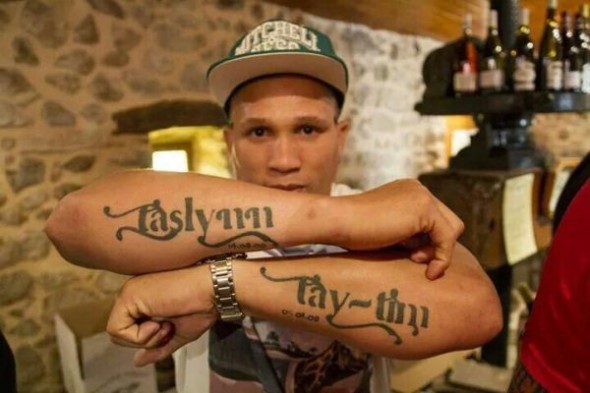

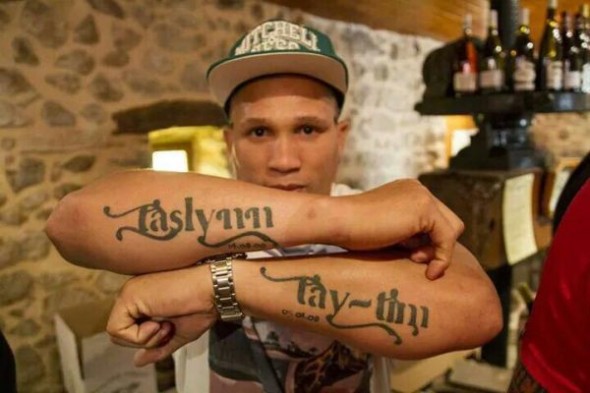

Today he lives in Lyon, France, playing rugby and raising his young family. The phone rings and a young voice peeps, “Oui”. The melange of French and Afrikaans accents belongs to Taytim, Januarie’s oldest daughter.

It’s a worry he will come to admit: “No not so much a worry as a battle to get my girls to speak Afrikaans. Maybe it will be easier with my son.” The father of two girls, Januarie’s son was born on June 17, by caesarean section, and his excitement shines.

Januarie and his family have lived in Lyon since 2011; his youngest daughter was just a year old at the time. With children it is easier, more important, to become part of a community, he explains. He reminds his daughters of their heritage but has encouraged them to make friends outside the circle of South African rugby families in France. “We raise our kids as we would in South Africa but we get to have this experience together. It has enriched our home life.”

Moment of freedom

As a rugby-mad 13-year-old, Januarie watched Mandela hand Pienaar the Webb Ellis Trophy to crown the Springboks champions of the rugby world. Till that moment Mandela had been an abstract hero who had had something to do with winning freedom for people who looked like him. “Seeing Mandela wearing a Springbok jersey for me was the moment freedom became a reality. I knew that I was free to earn the right to wear that jersey.”

The family’s deeply held Christian belief is the foundation for teaching their children that each and every person they meet is created by God. “Mandela was a living example of that. We could point to him and say ‘Live your life like that, in the spirit of goodness.’ Colour does not matter at all, like Mandela love your neighbour as you would want to be loved.

“When Mandela died I told Taytim and Taslynn it was his sacrifice that made their life possible,” he continues. His daughters – aged six and four – are still too young to understand how Mandela’s sacrifice made their father’s career possible, but the Januaries make a point of answering their questions truthfully.

South African rugby talent is seeded throughout the French league, most being white and Afrikaans-speaking, and they have built a community. For some, Mandela’s death raised the spectre of an old fear – now that the old man was gone white South Africans had to fear violence and death again.

Ending hatred

“Taytim picked up on those fears from friends and ask me if we would be able to go home again if there was going to be fighting. They were worried for their grandparents, for their cousins. Laken [Januarie’s wife] and I sat them down and explained that Mandela put a stop to the hatred. He laid peace at our feet and that is why we are all sad.”

The Januaries and the other players in France were glued to their TV screens, along with other South Africans and the rest of the world, mourning his death. As other players were doing, the TV coverage was an opportunity to explain to his children why Mandela’s life was one on which to model theirs. “Our church does a lot of outreach but on Mandela Day we celebrate his example by working with children. We hand out clothing and shoes. I think our girls understand better now why it’s such a special thing they help with.”

The Januaries are embedded in Lyon. As their French has improved – Januarie speaks fluently – their social circle has expanded beyond the rugby club. And, as much as they would like to be in South Africa to celebrate this year’s extra special Nelson Mandela Day with family and friends, they are living the spirit of the man in their new hometown. “Every day, Laken passes a man in a wheelchair. This year we will invite him into our home, feed him and see if there is any other way that we can help him.”

Januarie’s fondest rugby memory was a moment conjured by angels. It was a seven-second long passage of rugby that celebrated the joie de vivre, dexterity and extravagance of talent he brought to the game. Down to 14 men, trailing by five points, Januarie broke from a ruck 10 metres from New Zealand’s try line. He slippered the ball over Leon Macdonald, watched it bounce into his arms and dove over to tie the score. It was a moment that stands above all others in the history of the Tri-Nations tournament.

“You know, one day my children will ask me if it was as special as they say. Of course I will say yes but more importantly I will say it’s less special than the life of the man who made that moment possible, Nelson Mandela.”

By: Sulaiman Philip

Source: www.mediaclubsouthafrica.com