The history of South Africa

If the history of South Africa is in large part one of racial divisiveness, today it can also be seen as the story of the creation – from tremendous diversity – of a single nation. Sections in this article: Earliest inhabitants Colonial expansion Diamonds and British consolidation Gold and war Union and the ANC The […]

If the history of South Africa is in large part one of racial divisiveness, today it can also be seen as the story of the creation – from tremendous diversity – of a single nation.

- Sections in this article:

- Earliest inhabitants

- Colonial expansion

- Diamonds and British consolidation

- Gold and war

- Union and the ANC

- The gathering storm

- Three decades of crisis

- The death of apartheid

Earliest inhabitants

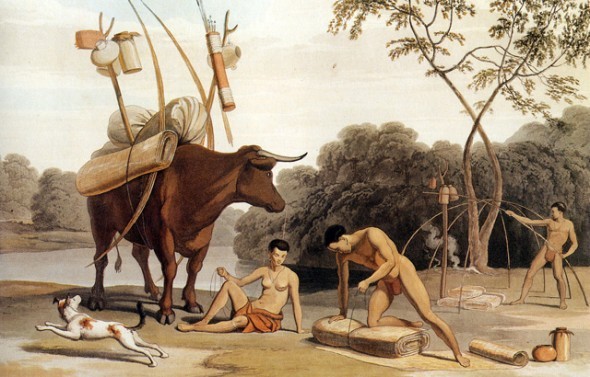

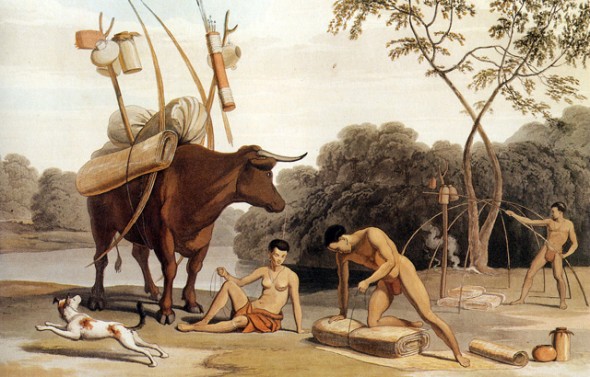

The earliest South Africans were the hunter-gatherer San (Bushmen) and the pastoral Khoekhoe (Hottentots), which were collectively the Khoisan. Both lived on the southern tip of the continent for thousands of years before written history began with the arrival of European seafarers. But before that, modern human beings had lived here for more than 100 000 years – making this country an archaeological treasure chest.

Other inhabitants were the Bantu-speaking people, who had moved into the north-eastern and eastern regions from the north, starting many hundreds of years before the arrival of Europeans. For example, Thulamela in the northern Kruger National Park is estimated to have been occupied in the 13th century. And at Mapungubwe, a settlement thought to stretch back to the 12th century, artefacts from China have been found.

When Jan van Riebeeck and his 90 men landed at the Cape of Good Hope in 1652 – to develop a vegetable garden to serve the Dutch East India Company’s eastern trade route – their relationship with the Khoekhoe was initially one of bartering. But a mutual animosity developed over issues such as cattle theft – and, no doubt, growing unease on the part of the Khoekhoe.

In 1657, slaves from the East were imported, adding Islam to South Africa’s racial and cultural mix. The descendants of some of the Khoisan, slaves from elsewhere in Africa and the East, and white colonists formed the basis of the group now known as “coloured”.

By the time Van Riebeeck left in 1662, 250 white people lived in what was beginning to look like a developing colony. Later governors encouraged immigration and in the early 1700s, independent farmers called trekboers began to push north and east.

Colonial expansion

As the colonists began moving east they encountered the Xhosa-speaking people living in the region that is today’s Eastern Cape. A situation of uneasy trading and more or less continuous warfare began to develop.

The British took the Cape over from the Dutch in 1795. Seven years later the colony was returned to the Dutch, only to come under British rule again in 1806.

In 1820 some 5 000 British settlers were placed on the eastern frontier as a buffer against the Xhosa – but many of them gave up the struggle with uncooperative land. The Xhosa reacted with heroic defiance to the pressure, but this ended tragically with the mass starvation that followed an 1857 prophecy that the whites would return to the sea if the Xhosa slaughtered their cattle and destroyed their crops.

By the second half of the 18th century, the colonists – mainly of Dutch, German and French Huguenot stock – had already begun to develop into the Afrikaner nation. Following the arrival of philanthropist missionaries (from 1806) and the emancipation of slaves (in 1834), about 12 000 discontented Afrikaner farmers, or Boers, uprooted and moved north and east: this was to be known as the Great Trek.

The early decades of the century also saw the rise to power of the great Zulu king, Shaka, whose wars of conquest caused a calamitous disruption of the interior known as the mfecane. Ironically, this denuded much of the area into which Trekkers now moved.

Initially, many Trekkers headed east into what is today the province of KwaZulu-Natal, under the leadership of Piet Retief. Intending to negotiate for land, Retief and his party were murdered at the kraal of Dingane, Shaka’s successor. In the war that followed, the Boers won the Battle of Blood River. They began to settle in Natal, but smaller conflicts followed and the British – fearing repercussions in the Cape – annexed Natal. On the highveld, however, two Boer republics were formed: the Orange Free State and the South African Republic (Transvaal or ZAR – Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek).

By the mid-1800s the area of white settlement stretched over virtually all of what is today South Africa. In some areas the Bantu-speakers maintained independence, but almost all were eventually to lose the struggle against white overlordship – except for the mountain stronghold of King Moshoeshoe’s Basotho. Known today as Lesotho, this country is entirely surrounded by South Africa, but has never been a part of it.

Diamonds and British consolidation

The Cape Colony was granted representative legislature in 1853 and self-government in 1872. Between these two dates, there was a dramatic development – the discovery of diamonds and the establishment of Kimberley. Despite rival claims by the Orange Free State, the ZAR and the West Griquas, the area was incorporated into the Cape Colony in 1880. The young Cecil John Rhodes made his fortune there.

Natal, meanwhile, proved ideal for cultivating sugar cane, which led to the importation of indentured labourers from India – the forebears of today’s Indian population.

With the late 19th century came aggressive colonial expansion. But the Zulus, under their king Cetshwayo, delivered resounding proof at Isandhlwana in 1879 that the British army was not invincible. However, they were defeated the following year and Zululand was eventually incorporated into Natal in 1897.

Gold and war

The unpopularity of the Transvaal’s president, TF Burgers, opened the way for British annexation in 1877, but Britain lost control after a rebellion at Majuba. Full internal autonomy was granted in 1884 – by which time the conservative and intensely pro-Afrikaner Paul Kruger had been elected president.

Two years later, when gold was discovered on the Witwatersrand, Kruger saw a threat to Afrikaner independence as huge numbers of newcomers (“uitlanders”) descended.

In the Cape, Rhodes had become Prime Minister. His vision of a federation of British-controlled states was well served by the discontent of the uitlanders and exasperation of the mining magnates in the ZAR. His first attempt at takeover, however, came to an ignominious end when his plan to have Leander Starr Jameson lead a raid into Johannesburg in response to a planned uitlander uprising failed. The uprising did not happen: Jameson rode precipitously into the Transvaal and had to surrender. Rhodes resigned.

The raid made Afrikaners more sympathetic to Kruger’s anti-British stance – with the Orange Free State forming a military alliance with the Transvaal. In Britain, however, Rhodes and Jameson were heroes. It kept up the pressure on Kruger and the Anglo-Boer/South African War began in October 1899. Up to half a million British soldiers squared up against some 65 000 Boers; black South Africans were pulled into the conflict on both sides.

Again Britain suffered a blow as the Boers set siege to Ladysmith, Kimberley and Mafeking (home at the time to a young black diarist named Sol Plaatje). Under Major General Herbert Kitchener and Field Marshal Sir Frederick Sleigh Roberts, however, the British offensive gained force and by 1900, Bloemfontein, Johannesburg and Pretoria were occupied. Kruger fled for Europe.

The Boer reply was to intensify guerilla war: General Jan Smuts led his troops to within 190km of Cape Town – and in response Kitchener adopted a scorched-earth policy and set up concentration camps in which some 26 000 Boer women and children and 14 000 black and coloured people died. The war ended in Boer defeat at the Peace of Vereeniging in 1902.

The delegation from the South African Native National Congress, the forerunner of today’s ruling African National Congress, that went to England in 1914 to convey the objections of the African people to the 1913 Land Act. In the back row, from left, is Walter Rubusana and Saul Nsane; in the front row is Thomas Mapikela, John Dube and Sol T Plaatje. (Image: African National Congress)

The delegation from the South African Native National Congress, the forerunner of today’s ruling African National Congress, that went to England in 1914 to convey the objections of the African people to the 1913 Land Act. In the back row, from left, is Walter Rubusana and Saul Nsane; in the front row is Thomas Mapikela, John Dube and Sol T Plaatje. (Image: African National Congress)

Union and the ANC

Many hoped the British victory would put all four colonies on an equal and just footing, but the treaty left their franchise rights to be decided by the white authorities. The ex-Boer republics retained the whites-only franchise. In 1909 a delegation appointed by the South African Native Congress went to London to plead their case. But when the Union of South Africa came into being on 31 May 1910, the only province with a non-racial franchise was the Cape and blacks were barred from being members of parliament.

The South African Party, a merging of the previous Afrikaner parties, held power under General Louis Botha. Repressive measures were not long in coming – such as the 1913 Land Act, which reserved 90% of the country for whites.

By this time, the African National Congress (ANC) had come into being. Formed in Bloemfontein on January 8 1912, it united an educated elite, rural classes and tribal structures. Sol Plaatje was secretary and the first president was the Rev John L Dube. Both were part of a second unsuccessful delegation to London, this time to protest against the land grab.

Resistance became more outspoken and militant, especially when several hundred black women marched in Bloemfontein to protest against passes. Similar protests were held in other places.

Indians were also suffering under viciously racist treatment: in 1891 they had been expelled from the Orange Free State altogether. Mohandas (Mahatma) Gandhi, then a young lawyer, had become a leading figure in Indian resistance. The struggle against the £3 Indian poll tax in Natal involved a mass strike in which a number of Indians were killed, but achieved success when the tax was removed in 1914.

In the white camp, Botha and Smuts were in favour of reconciliation with English South Africans. But they did not represent all embittered Afrikaners and JBM Hertzog formed the more conservative National Party. When South Africa entered the First World War in support of Britain, anti-British Afrikaners unsuccessfully rebelled.

Still hoping for backing from the British government, the ANC supported the war and unknown numbers of black soldiers died. As a result of the war, South Africa gained control over the previously German-held South West Africa (now Namibia).

With the inspiration of the Russian Revolution, the post-war period was marked by strikes. In 1918 a million black mine workers went on strike; 71 000 did the same in 1920. Between those strikes, Botha died and Smuts became Prime Minister.

In 1922 a different group of miners were to strike. When the Chamber of Mines let lower-paid Africans do semi-skilled work, white miners reacted violently and were suppressed by Smuts’s military. Hertzog’s Nationalists found increased support in the white Labour Party, and an election pact saw Smuts ousted and Hertzog become Prime Minister in 1924.

The government’s popularity declined, however, with economic depression in the 1930s, forcing Hertzog into a Smuts coalition government in 1933 (the year before South Africa became independent from Great Britain). Their parties fused as the United Party, but Hertzog’s move was balanced by the breaking away on the right of DF Malan’s new National Party. In 1936 black Cape voters were removed from the common roll.

The Hertzog-Smuts coalition fell apart with the Second World War, Smuts winning the battle to take South Africa into the conflict. Afrikaner opposition to the war strengthened Malan’s support base.

At the same time, developments in the ANC symbolically marked the start of what was to be nearly 50 years of conflict with the National Party. In April 1944 the ANC Youth League was formed, with Nelson Mandela as its secretary.

The National Party, meanwhile, was gathering strength: in a surprise result, it gained power in the 1948 election and apartheid became official government ideology.

The gathering storm

The 1950s were to bring increasingly repressive laws and increasing resistance. The Group Areas Act and the Population Registration Act were passed in 1950, the pass laws came in 1952 and the Separate Amenities Act in 1953. In that year, Malan retired and JG Strijdom became Prime Minister.

In reaction to this came the Defiance Campaign of 1952, which led to the jailing of thousands. The result was increased unity among resistance groups with the forming of the Congress Alliance, which included black, coloured, Indian and white organisations, as well as the South African Congress of Trade Unions.

In 1954 a campaign against the deliberately inferior Bantu education system was launched.

The following year saw two significant events. Unable to gain the two-thirds required to remove coloureds from the common voters’ roll, the government changed the composition of the Senate by increasing its size (and consequently the Nationalist majority).

The second watershed moment came when the Freedom Charter – based on the principles of human rights and non-racialism – was signed in Soweto on June 26 1955. Reaction was swift: the following year 156 leaders of the ANC and its allies were charged with high treason. The longest trial in South African history was to lead to the acquittal of all accused in 1961.

Strijdom died in 1958, to be succeeded by HF Verwoerd. The following year representatives of blacks were removed from both houses of parliament and the Cape provincial council; on the other side of the political fence, the Pan-Africanist Congress (PAC), founded by Robert Sobukwe, broke away from the Congress Alliance. The stage was set for the even more polarised 1960s.

Three decades of crisis

A turning point came at Sharpeville on March 21 1960 when a PAC-organised passive anti-pass campaign came to a bloody conclusion with police killing 69 unarmed protesters. A state of emergency was declared and the ANC, PAC and other organisations were banned. The resistance went underground.

The country’s isolation increased in 1961 when, following a white referendum, South Africa became a republic and left the Commonwealth.

Mandela, meanwhile, had travelled through Africa. On his return in August 1962 he was arrested and received a three-year sentence for incitement.

In July 1963 a police raid on Lilliesleaf farm in Rivonia led to the arrest of several of Mandela’s senior ANC colleagues, including Walter Sisulu. They were charged with sabotage and Mandela was brought from prison to stand trial with them. All were sentenced to life imprisonment and taken to Robben Island in 1964.

In September 1966 BJ Vorster became Prime Minister after the assassination in parliament of Verwoerd. Segregation became even stricter.

The first half of the next decade was marked by repression, militancy and strikes. On June 16 1976 the youth of Soweto marched against being taught in the medium of Afrikaans; police fired on them, precipitating massive violence. Nevertheless, an attempt was made to further the “homeland” policy, with Transkei being the first to accept nominal independence later that year.

A new movement known as Black Consciousness had become increasingly influential. The death as a result of police brutality of its charismatic founder, Steve Biko, shocked the world in 1977.

PW Botha, who became Prime Minister in 1978, tried to co-opt the coloured and Indian population in the early 1980s with a new constitution establishing a Tricameral Parliament, with separate houses for these groups. Opposition came from both left and right. The United Democratic Front, a coalition of anti-apartheid groups, organised boycotts of coloured and Indian elections in 1984. The country was being governed – as far as it was governable – under a state of emergency and in a spiral of resistance and repression.

Among the other organisations in the spotlight at this time were the trade union body Cosatu and Chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi‘s Inkatha, the latter involved in bloody conflict with pro-ANC factions.

The death of apartheid

elections, for the PWV province (now

Gauteng). The photographs of party

leaders were reproduced to help illiterate

people cast their vote.

In 1989 the logjam started to break up. Negotiations had begun between Mandela and PW Botha, but these were secret. Dissension within the National Party and Botha’s ill health led to his resignation; he was replaced by FW de Klerk. After an election in September, De Klerk released Walter Sisulu and seven other political prisoners.

On February 2 1990, De Klerk lifted restrictions on 33 opposition groups, including the ANC, the PAC and the South African Communist Party. On February 11 Mandela was released after 27 years in prison.

The dismantling of restrictive legislation began. Political groups started negotiating the ending of minority rule and in 1992 the white electorate endorsed De Klerk’s stance in a referendum. But violence continued, a massacre at the township of Boipatong causing the ANC to withdraw temporarily from constitutional talks.

In 1993, however, an agreement was reached on a Government of National Unity which would allow a partnership of the old regime and the new.

This optimism was shattered by the assassination of Chris Hani, the secretary general of the Communist Party: only a prompt appeal to the nation by Mandela averted a massive reaction. At the end of the year an interim Constitution was agreed to by 21 political parties.

South Africa’s first democratic election was held on 26, 27 and 28 April 1994, with victory going to the ANC. Nelson Mandela was sworn in as President on May 10. FW de Klerk and the ANC’s Thabo Mbeki were Deputy Presidents.

Mandela’s presidency was characterised by the negotiation of a new Constitution; a start on the massive task of restructuring the civil service and tackling the results of apartheid; and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, set up to investigate the wrongs of the past.

Source: www.mediaclubsouthafrica.com