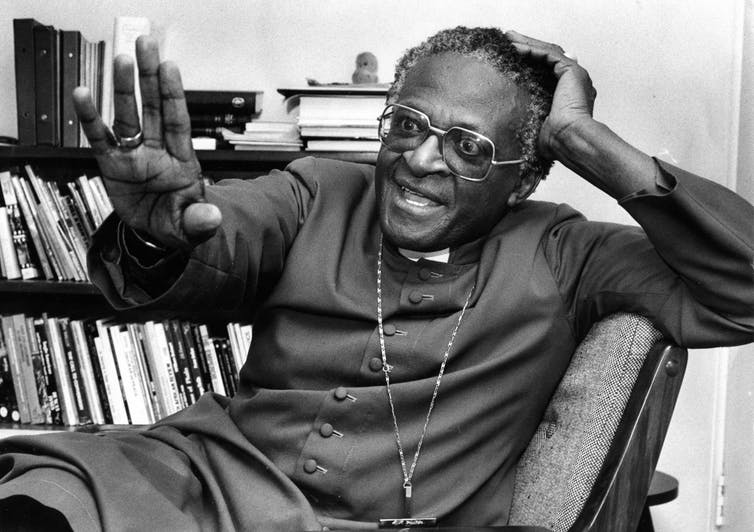

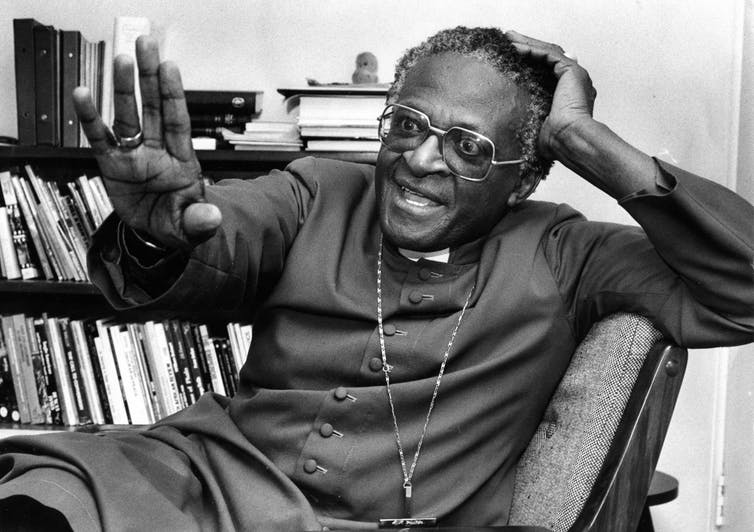

Desmond Tutu’s Long History of Fighting for Lesbian and Gay Rights

Archbishop Desmond Mpilo Tutu is mostly known to the world for his highly prominent role in the campaign against apartheid in South Africa. This role was internationally recognised by the awarding of the 1984 Nobel Peace Prize. Tutu continued his activism even after the country’s democratic transition in South Africa in the early 1990s. Among […]

Archbishop Desmond Mpilo Tutu is mostly known to the world for his highly prominent role in the campaign against apartheid in South Africa. This role was internationally recognised by the awarding of the 1984 Nobel Peace Prize.

Tutu continued his activism even after the country’s democratic transition in South Africa in the early 1990s. Among other things, he served as chair of the country’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission which sought to deal with the crimes and injustices under apartheid, and to bring about justice, healing and reconciliation in a wounded society. He retired as Archbishop of Cape Town in 1996.

In more recent years Tutu has become known for his strong advocacy on issues of sexuality, in particular the rights of lesbian and gay people. For instance, in 2013, he made global headlines with a clear and succinct statement, in typical Tutu fashion, that he:

would rather go to hell than to a homophobic heaven.

Tutu is by far the most high-profile African, if not global, religious leader to support lesbian and gay rights. This has added to his international reputation as a progressive thinker and activist, especially in the western world. But his stance has been met with suspicion on the African continent itself. A fellow Anglican bishop, Emmanuel Chukwuma from Nigeria, even declared him to be “spiritually dead”.

For distant observers, Tutu’s advocacy around sexuality might appear to be a recent phenomenon. For his critics, it might be another illustration of how he has tried to be the darling of white liberal audiences in the Western world.

In fact his commitment to defending gay and lesbian rights isn’t a recent development; it dates as far back as the 1970s. In addition, it is very much in continuity with his long-standing resistance against apartheid and his relentless defence of black civil rights in South Africa.

Common thread

Shortly after the end of apartheid in 1994, Tutu wrote that

If the church, after the victory over apartheid, is looking for a worthy moral crusade, then this is it: the fight against homophobia and heterosexism.

Driving both struggles is Tutu’s strong moral and political commitment to defending the human dignity and rights of all people. Theologically, this is rooted in his conviction that every human being is created in the image of God and therefore is worthy of respect.

In the 1980s, Tutu and other Christian leaders had used the concept of ‘heresy’ to denounce apartheid in the strongest theological language. They famously stated that “apartheid is a heresy”, meaning that it is in conflict with the most fundamental Christian teaching.

Tutu also used another strong theological term: blasphemy, meaning an insult of God-self. In 1984, he wrote:

Apartheid’s most blasphemous aspect is … that it can make a child of God doubt that he is a child of God. For that reason alone, it deserves to be condemned as a heresy.

More than a decade later, Tutu used very similar words to denounce homophobia and heterosexism. He wrote that it was “the ultimate blasphemy” to make lesbian and gay people doubt whether they truly were children of God and whether their sexuality was part of how they were created by God.

Tutu’s equation of black civil rights and lesbian and gay rights is part of a broader South African narrative and dates back to the days of the apartheid struggle. Openly gay anti-apartheid activists, such as Simon Nkoli, had actively participated in the liberation movement, and had successfully intertwined the struggles against racism and homophobia.

On the basis of this history, South Africa’s Constitution, adopted in 1996, included a non-discrimination clause that lists sexual orientation, alongside race and other characteristics. It was the first country in the world to do so, and Tutu had actively lobbied for it.

A decade later, South Africa became the sixth country in the world to legalise same-sex marriage.

Attitudes still need work

Arguably, these legal provisions did not automatically translate into a change of social attitudes towards lesbian and gay people at a grassroots level. Homophobia remains widespread in South African society today.

Tutu’s own church, the Anglican Church of Southern Africa, continues to struggle with gay issues. In 2015 his daughter, Mpho Tutu, had to give up her position as an ordained priest after she married a woman. Tutu gave the newlywed couple a blessing anyway.

The question of same-sex relationships and the status of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex people continues to be controversial across the world. In this context, Tutu is an influential figure who uses his moral authority to help shape the debates.

His equation of racial and sexual equality is particularly important, as it foregrounds how the struggle for justice, equality and human rights are interconnected: we cannot claim rights for one group of people while denying them to others.

This article is an abbreviated version of a chapter about Desmond Tutu in the book Reimagining Christianity and Sexuality in Africa, co-authored by Adriaan van Klinken and Ezra Chitando, and to be published with Zed Books in London (2021).![]()

Adriaan van Klinken, Associate Professor of Religion and African Studies, University of Leeds

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.