Confessions of a stay-at-home dad

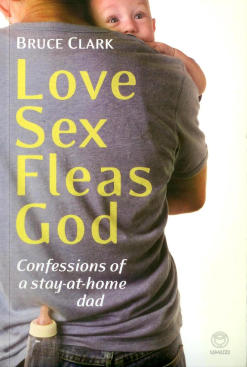

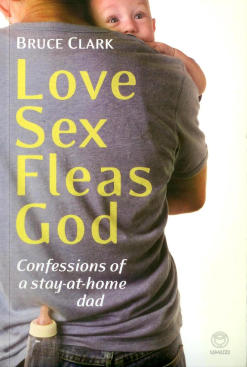

Bruce Clark is one of those unusual things – a stay-at-home dad. In his uplifting memoir Love Sex Fleas God, aptly subtitled “Confessions of a stay-at-home dad”, he talks about his troubled childhood and his ultimately successful search for direction in life. The captivating title came out of a paragraph Clark wrote in response to publisher Umuzi‘s […]

Bruce Clark is one of those unusual things – a stay-at-home dad. In his uplifting memoir Love Sex Fleas God, aptly subtitled “Confessions of a stay-at-home dad”, he talks about his troubled childhood and his ultimately successful search for direction in life.

The captivating title came out of a paragraph Clark wrote in response to publisher Umuzi‘s request to describe the book – “Love sex fleas God” appeared, and the publisher said to him: “That’s the title!”

Clark recounts with charm and humour his story – his brief marriage ceremony, the pregnancies and deliveries, and his adjustment to being a father, something that comes naturally to him despite his own tough upbringing – in the first half of the book.

Despite a childhood that included being abandoned by his mother, the author doesn’t let this debut book become consumed by his harsh life experiences – at the end of the second chapter he writes that “This book is not at all about self-pity or anger. It’s a book about love.”

It’s also about being vulnerable and honest and at ease with one’s feelings, something he learnt to do from a young age as he was surrounded by women – his mother, his sister and his grandmother.

Finding direction

Clark’s story of neglect and alienation mirrors that of countless young men in South Africa, who may never get to tackle the root causes of their trauma. A good deal are raised by their grandmothers, often a result of parents dying of Aids. Like Clark, many too are raised in homes with absent fathers.

(Images: Random House Struik)

His desperately poor grandmother was not able to adequately see to his needs, and the problem was exacerbated because Clark moved schools frequently.

Experts agree that neglectful parenting – which encompasses all kinds of physical and emotional ill-treatment – doesn’t only upset the child, but the effects spill out into the family and the community, contributing to problems like violence, school drop-outs and unemployment.

This makes Clark’s turnaround more remarkable and is a testament not only to his own character, but to the resilience of the South African spirit.

Turned out on the streets at 16, Clark finds himself without a matric and without a job. After two years in the army he takes an aptitude test and learns to be a computer programmer, but is eventually retrenched, and ends up feeling despondent, useless and directionless.

Meeting “a good woman”, and having children saves him, and it’s as a husband and father that he’s able to find himself. He has worked through his anger towards the world, and his life is given meaning by his deep love for his family.

His devotion to his children glitters. He answers his son’s question “How many days until the end of the world?” by phoning God, after which his son tells a friend, with great pride, that his father has God’s phone number. He playfully goes along with his five-year-old daughter’s request for a new dress, teasing her, until she turns to him and says: “You have a crack in your bum.”

Traumatic upbringing

The mood shifts in the second half of the book, where he describes his upbringing in a Scientology home, where his mother subjects him to distress and neglect, dumping him and his sister with his grandmother, who becomes their surrogate but unsuitable mother.

His anger is never far from the surface, but still he manages to spend time with his mother at the end of her life, work through his resentment for her, and in the end, love her.

“When my mother died my relationship with her was the best it had ever been,” he says. “She got to see my life through my eyes and vice versa. I spent too many years regarding her as a failed mother instead of recognising the fact she was an outstanding human.”

It was a healing experience. “I suppose the fact that in the end I went from willing her to live to willing her to die was a testament to me moving to the side of love. She suffered so very much and I wanted it to end.” Clark’s mother died of cancer.

Two years to write

Clark says it took him around two years to write the book, but that it “tickled my fancy for years and years”. A school drop-out, he says that the only thing he could really do at school was to write.

His first serious piece of writing was a eulogy for Jack, the car guard at Dabulamanzi Canoe Club in Greenside, Johannesburg, where Clark went to train for the Dusi Canoe Marathon, a 120km canoe race held in KwaZulu-Natal each year. For years the two of them had had a fraught relationship, which “brought out everything I hated in myself”.

All that changed when he brought his children to the dam, and noticed how naturally Jack engaged with them. He started liking Jack, even looking out for him – they developed a close relationship. Several years later Jack, who was raising his grandchildren on his own, died. Clark was distraught, and wrote the eulogy, which was posted on the kayaking email group. This was picked up by the editor of Afrikaans newspaper Rapport, and Clark was asked to write several articles for the newspaper.

Random House then approached him, suggesting a book, and the ball started rolling.

Clark says he found the book difficult to write, not knowing which way around to start. For instance, he wrote the last page first – “that came very easily”. After that, the challenge was getting the sequence right.

Favourable feedback

The reaction to the book has been “pretty good”, he says. “It feels quite cathartic, and satisfying. I appreciate it when people say it is well written, that means more to me than anything else.”

He adds that he didn’t anticipate how many people saw themselves in the book, particularly in their struggles with religion and personal issues. They found it comforting to read about how he had coped with his upheavals.

Has being a parent changed him? “I am a lot more tolerant, humble and patient, a better person,” he says.

More importantly, he sees himself as a writer now, who wouldn’t go back into formal employment. He has started writing again, although he doesn’t know where it will lead him. It’s more important to be happily married and a devoted parent.

By: Lucille Davie

Source: www.mediaclubsouthafrica.com