Astronomers used machine learning to mine data from South Africa’s MeerKAT telescope: what they found

New telescopes with unprecedented sensitivity and resolution are being unveiled around the world – and beyond. Among them are the Giant Magellan Telescope under construction in Chile, and the James Webb Space Telescope, which is parked a million and a half kilometres out in space. This means there is a wealth of data available to […]

New telescopes with unprecedented sensitivity and resolution are being unveiled around the world – and beyond. Among them are the Giant Magellan Telescope under construction in Chile, and the James Webb Space Telescope, which is parked a million and a half kilometres out in space.

This means there is a wealth of data available to scientists that simply wasn’t there before. The raw data off just a single observation from the MeerKAT radio telescope in South Africa’s Northern Cape province can measure a terabyte. That’s enough to fill a laptop computer’s hard drive. MeerKAT is an array of 64 large antenna dishes. It uses radio signals from space to study the evolution of the universe and everything it contains – galaxies, for example. Each dish is said to generate as much data in one second as you’d find on a DVD.

Machine learning is helping astronomers to work through this data quickly and more accurately than poring over it manually. Perhaps surprisingly, despite increasing reliance on computers, up until recently the discovery of rare or new astrophysical phenomena has completely relied on human inspection of the data.

Machine learning is essentially a set of algorithms designed to automatically learn patterns and models from data. Because we astronomers aren’t sure what we’re going to find – we don’t know what we don’t know – we also design algorithms to look out for anomalies that don’t fit known parameters or “labels”.

This approach allowed my colleagues and I to spot a previously overlooked object in data from MeerKAT. It sits some seven billion light years from Earth (a light year is a measure of how far light would travel in a year). From what we know of the object so far, it has many of the makings of what’s known as an Odd Radio Circle (ORC).

Odd Radio Circles are identifiable by their strange, ring-like structure. Only a handful of these circles have been detected since the first discovery in 2019, so not much is known about them yet.

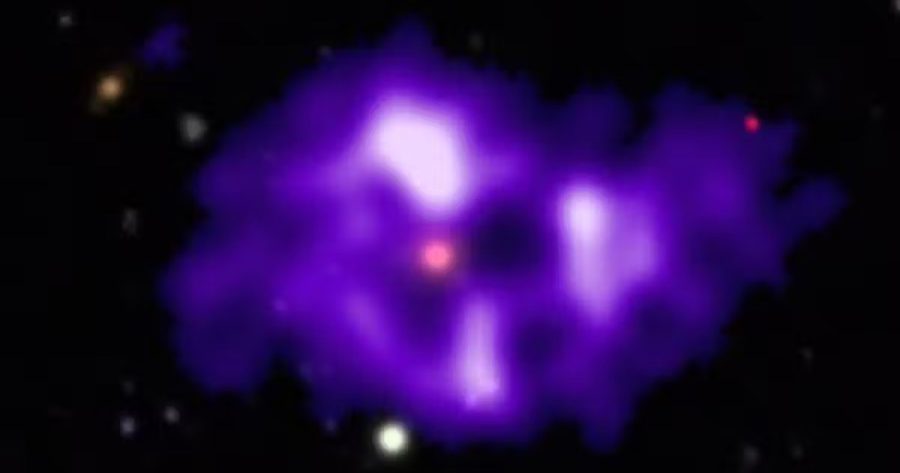

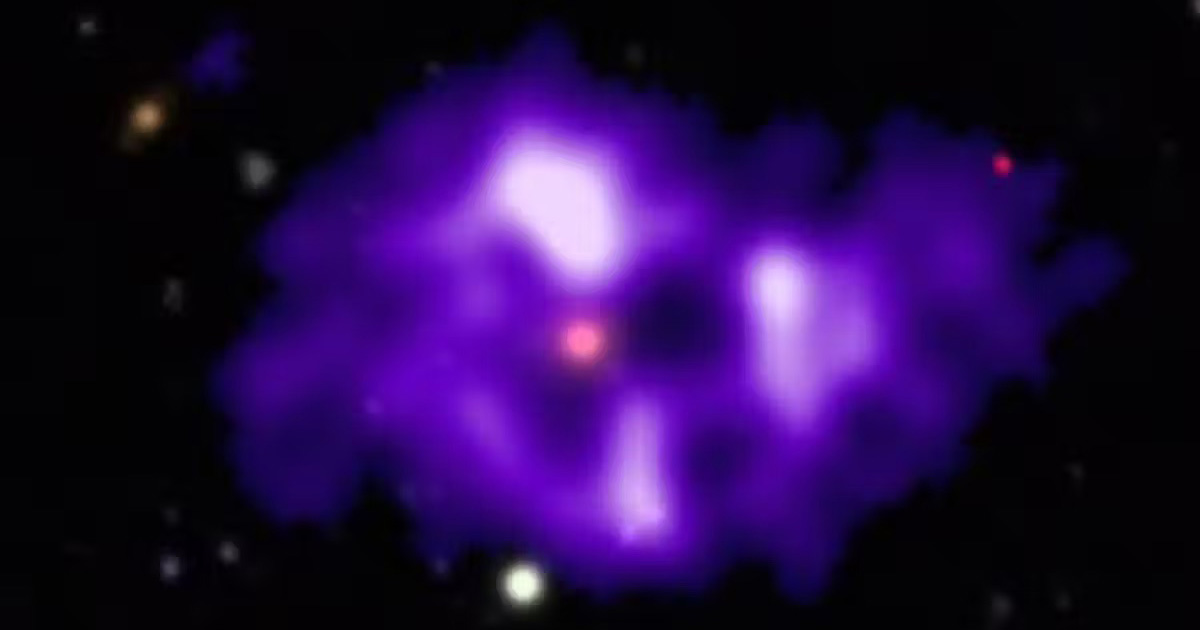

In a new paper we outline the features of our potential Odd Radio Circle, which we’ve named SAURON (a Steep and Uneven Ring Of Non-thermal Radiation). SAURON is, to our knowledge, the first scientific discovery made in MeerKAT data with machine learning. (There have been a handful of other discoveries assisted by machine learning in astronomy.)

Not only is discovering something new incredibly exciting, new discoveries are critical for challenging our understanding of the cosmos. These new objects may match our theories of how galaxies form and evolve, or we may need to change how we see the universe. New discoveries of anomalous astrophysical objects help science to make progress.

Identifying anomalies

We spotted SAURON in data from the MeerKAT Galaxy Cluster Legacy Survey. The survey is a programme of observations conducted with South Africa’s MeerKAT telescope, a precursor to the Square Kilometre Array. The array is a global project to build the world’s largest and most sensitive radio telescope within the coming decade, co-located in South Africa and Australia.

The survey was conducted between June 2018 and June 2019. It zeroed in on some 115 galaxy clusters, each made up of hundreds or even thousands of galaxies.

That’s a lot of data to sift through – which is where machine learning comes in.

We developed and used a coding framework which we called Astronomaly to sort through the data. Astronomaly ranked unknown objects according to an anomaly scoring system. The human team then manually evaluated the 200 anomalies that interested us most. Here, we drew on vast collective expertise to make sense of the data.

It was during this part of the process that we identified SAURON. Instead of having to look at 6,000 individual images, we only had to look through the first 60 that Astronomaly flagged as anomalous to pick up SAURON.

But the question remains: what, exactly, have we found?

Is SAURON an Odd Radio Circle?

We know very little about Odd Radio Circles. It is currently thought that their bright, blast-like emission is the wreckage of a huge explosion in their host galaxies.

The name SAURON captures the fundamentals of the object’s make-up. “Steep” refers to its spectral slope, indicating that at higher radio frequencies the “source” (or object) very quickly grows fainter. “Ring” refers to the shape. And the “Non-Thermal Radiation” refers to the type of radiation, suggesting that there must be particles accelerating in powerful magnetic fields. SAURON is at least 1.2 million light years across, about 20 times the size of the Milky Way.

But SAURON doesn’t tick all the right boxes for us to say that it’s definitely an Odd Radio Circle. We detected a host galaxy but can find no evidence of radio emissions with the wavelengths and frequency that match those of host galaxies of the other known ORCs.

And even though SAURON has a number of features in common with Odd Radio Circle1 – the first Odd Radio Circle spotted – it differs in others. Its strange shape and its oddly behaving magnetic fields don’t align well with the main structure.

One of the most exciting possibilities is that SAURON is a remnant of the explosive merger of two supermassive black holes. These are incredibly dense objects at the centre of galaxies such as our Milky Way that could cause a massive explosion when galaxies collide.

More to come

More investigation is required to unravel the mystery. Meanwhile, machine learning is quickly becoming an indispensable tool to find more strange objects by sorting through enormous datasets from telescopes. With this tool, we can expect to unveil more of what the universe is hiding.![]()

Michelle Lochner, Senior Lecturer in Astronomy, University of the Western Cape

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.