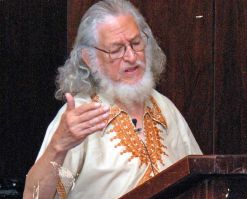

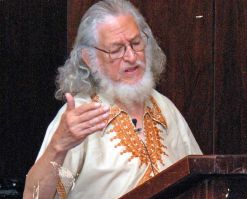

A wild beard and fierce convictions

Dennis Brutus pensively stroked his silver beard with both hands, thinking about the time in 1959 when Brazilian football club Portuguesa Santista were planning to visit South Africa to play against an all-white Western Province team. The Brazilian side was willing to drop their black players for the visit, in deference to apartheid, he said. […]

Dennis Brutus pensively stroked his silver beard with both hands, thinking about the time in 1959 when Brazilian football club Portuguesa Santista were planning to visit South Africa to play against an all-white Western Province team. The Brazilian side was willing to drop their black players for the visit, in deference to apartheid, he said. But Brutus was not willing to let that happen.

“I phoned the president [Juscelino Kubitschek] of Brazil directly,” he recalled. “I explained the situation to him, saying we could not allow racism to prevail in sport and asked him to intervene. He then cabled the team, ordering them not to play in South Africa.”

This is one anecdote of many in the book, Time with Dennis Brutus, in which author Cornelius Thomas characterises the late poet, journalist and activist by two things: his unfaltering love for humanity and that beard, which he wore until his death in December 2009. Thomas’s other nonfiction works, Dust in My Coffee and Finding Freedom in the Bush of Books, give a voice to the lesser known bastions of the liberation struggle. Time with Dennis Brutus is no different.

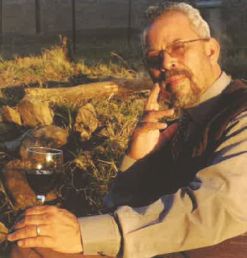

It describes the enjoyable moments he shared with Brutus in the last four years of the activist’s life. “Our conversations brought out the private and personal Dennis. I thought I had to share some of that with posterity,” the author says.

(Image: Marcus Thomas)

A memorable recollection from the days spent with Brutus while writing his book was a visit to 20 Shell Street in North End, Port Elizabeth. Brutus and his young family lived here during apartheid while he was under a state banning order. “He wanted to pause there, I guess to reflect and reminisce a bit. We sat there for maybe 30 minutes and he told me about his family life, and how he beat his banning order. I think it was a special moment for him and certainly a poignant one for me.”

Thomas first met “the man with long steel-grey hair” at the National Arts Festival in Grahamstown in 2000. He was interviewing the activist and feminist writer Lauretta Ngcobo when he bumped into Brutus. “He was not intense,” he recalls. “He was jovial and seemed a fun-loving guy. I liked him right away.”

Such a first impression was in contrast to the man’s fiery activism, evident in his successful campaign to have apartheid South Africa banned from participating in the Olympic Games. “Dennis believed that the individual could make a difference. He looked into the world and saw many wrongs and he felt called to address them, without deference or political correctness,” explains Thomas.

Sport as a platform for protest

The first time Brutus turned to sport as a “terrain on which to fight for fairness” was in the 1940s. At the time, Seretse Khama, a young black high jumper, was not allowed to compete against white athletes. That young athlete went on to become the first president of Botswana, and received a KBE from Queen Elizabeth. Brutus went on to set up the South African Sports Association in October 1958 with GK Rangasamy and Arthur Lutchman. The name was neutral, said Brutus, and it did not give too much away. “We stood for merit on a non-racial basis in sport.”

(Image: IOL News)

He was banned from literary, academic and political activities in 1961, yet he went on to help establish the South African Non-Racial Olympic Committee in 1963, which led to the international sports boycott against apartheid South Africa. As a result, he was arrested and imprisoned on Robben Island. While incarcerated, he heard that South Africa had been suspended from the 1964 Tokyo Olympics.

In 2007, Brutus was nominated for induction into the South African Sports Hall of Fame, which is organised by veteran rugby player Naas Botha. Ever the activist, he declined, saying: “It is incompatible to have those who championed racist sport alongside its genuine victims.”

Protest poetry

Brutus’s writings always had an air of protest about them. The Gale Contemporary Black Biography series described his Sirens, Knuckles and Boots, published in 1963, as his way of shouldering his own burdens in the fight against racism. It said that although his words carried a tone of dissent, his poems “lack any element of self-pity”.

After serving 18 months on Robben Island, he published Letters to Martha and Other Poems from a South African Prison in 1968. Addressed to his sister-in-law, the poems were conversational and direct, so that ordinary people could understand them. This literary change came about after he spent five months in solitary confinement, during which time he “re-examined his verse and his attitudes toward creative self-expression”.

Thomas explains that Brutus’s writing was inspired by the discrimination he witnessed while growing up. “I think growing up when segregation hardened and when apartheid worked its way through our social fabric, he saw wrongs everywhere: unfair discrimination, evictions, forced removals, denial of opportunity.”

He was also prompted to take action by the inactivity of others. “Dennis had courage, a keen mind, and a social conscience. My book shows that even when he was in junior high, he was prepared to mobilise against wrong.”

Brutus’s defiance inspired a generation of activists, including Thomas, who became an activist as a student at the University of the Western Cape. “He fought for the poor, on every frontline where greed and oppression tried to halt the march towards a more human society.”

Still relevant

He may have been one of the lesser known political activists of the liberation struggle, but this does not mean Brutus’s efforts are to be ignored. According to Thomas, South Africans today need to heed his message more than ever before. Brutus believed every generation should fight against the social ills of hunger, poverty, oppression and denial of opportunity. “As a modern people, who claim to embrace the human race and a universal human rights culture, we cannot retire into privacy as if ‘the struggle’ was over,” Thomas explains.

Brutus’s successor would have to be steadfast to ward off today’s challenges, Thomas says, pointing to the writer and sociologist, Ashwin Desai, as the candidate to take over from where Brutus left off. “Like Dennis, [Desai] is eloquent and fearless, and his heart is in the right place. With the poor, his body is on the line, opposing the forces of injustice and greed.”

As for Brutus, he thought highly of Desai. Commenting on the latter’s book, We Are the Poors, Brutus described the author as one of South Africa’s leading activist intellectuals. And then, in his Dennis Brutus Memorial Lecture in Port Elizabeth in 2012, Desai returned the compliment, saying he hoped his address would take up Brutus’s challenge of querying the “form and content of the national liberation struggles” and the “democratic transition in South Africa”.

Desai does not see himself as a role model. “But if a budding young activist were to look for a role model,” says Thomas, “the best I can think of is Ashwin.”

South Africa today

Before his death, Brutus was critical of the direction South Africa had taken. Thomas says the old activist felt the revolution had been betrayed and that one set of oppressors had been replaced by another. “He was deeply disturbed by the mindless embrace of neo-liberalism.”

He notes that the ruling classes are crafting mythologies based on half-truths, and that activists such as Brutus are effectively being written out of the national narrative. “Any new ruling party wants to write history its way, perhaps [at the same time] marginalising or excluding others. There is much untruthfulness in such a process. And Dennis would have us speak truth to power.”

Indeed, in a passage in Time with Dennis Brutus, the activist speaks honestly about present-day global challenges. At a social gathering in East London in October 2008, Brutus said people had to embrace new causes or allow them to find us. “We live in new realities today and we must tackle, politically, the challenges of the day – corporate greed, globalisation, the depletion of the earth’s resources.”

He was an activist until his dying breath, aiming to attend the 2009 UN Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen. According to Thomas, Brutus believed climate justice was humanity’s new cause. Sadly, he did not make it to Denmark – he died in his sleep at the age of 85.

Though Thomas’s book is an attempt to hold on to Brutus’s legacy, he does not intend on being the messenger for the latter’s ideologies. Instead, he leaves those theories to academics and their dissertations. Thomas prefers to share Brutus’s voice with generations to come. “My book is but a friendly salute to him. To thank him for allowing me into his company, into his thoughts, and, I would like to think, into his heart.”

By: Shamin Chibba

Source: www.mediaclubsouthafrica.com