Happy Anniversary Joburg: 130 Years Old and Still Growing

Johannesburg is 130 years old this year. What started off as a tented village on the dusty Highveld is now a huge city with a population of about five million. Everyone knows that ‘Johannesburg’ is synonymous with gold, and is also known as ‘the City of Gold’ and ‘Egoli’. On this 130th anniversary of its […]

Johannesburg is 130 years old this year. What started off as a tented village on the dusty Highveld is now a huge city with a population of about five million. Everyone knows that ‘Johannesburg’ is synonymous with gold, and is also known as ‘the City of Gold’ and ‘Egoli’. On this 130th anniversary of its founding, having a look at its earliest years is interesting and appropriate…

Prior to 1886, the independent Zuid Afrikaanse Republiek (ZAR) had a small population that was largely rural, and the few towns were small. Various prospectors had been exploring likely-looking sites on the many farms and gold was discovered at what were later called Barberton and Pilgrim’s Rest.

Overnight as it were, these mining areas became boom towns with a flood of prospectors and miners.

However the amount of gold at these sites was limited. When it ran out or was too costly to mine, the towns shrunk, and are now simply a part of South Africa’s history.

The first recorded discovery of gold on the Witwatersrand was made by Jan Gerrit Bantjes in June 1884 on the farm Vogelstruisfontein and was followed soon thereafter, in September, by the Struben brothers who uncovered the Confidence Reef on the farm Wilgespruit, near present-day Roodepoort.

However, these were minor reefs, and the credit for the discovery of the main gold reef must be attributed to George Harrison, who recognised an outcropping of a conglomerate likely to contain gold on the farm Langlaagte. In April 1886 he applied to the government for a licence, and the news got out.

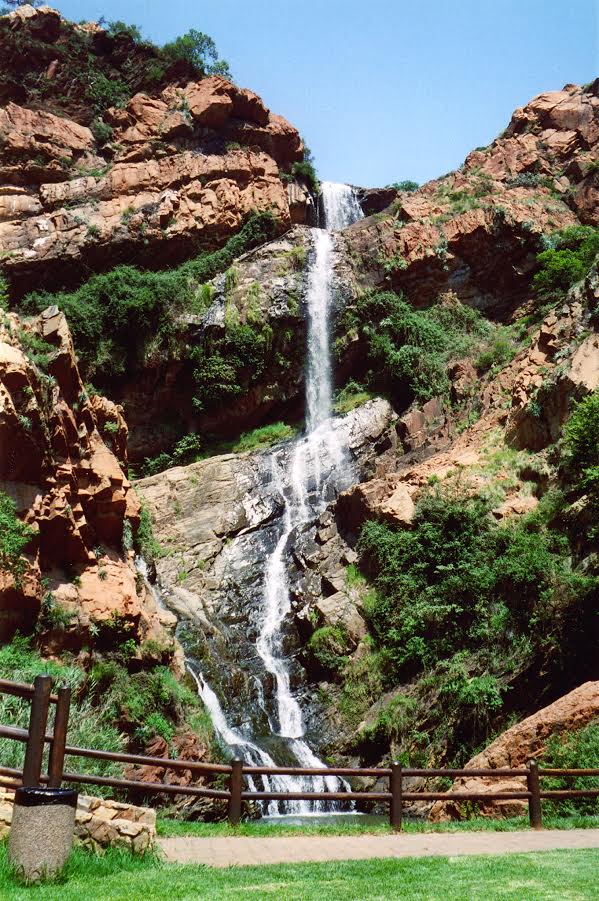

The Witwatersrand is a 36 kilometre long north-facing scarp. The Afrikaans ‘Witwatersrand’ translates as ‘the ridge of white waters’.

This ridge is 1 753 metres above sea level. It was so-named because it consists of a hard, erosion-resistant quartzite sedimentary rock, with several north-flowing streams and spectacular waterfalls. The gold Harrison found was in fact part of the Witwatersrand’s vast main gold reef.

One may well ask why the world’s most prolific deposits of gold were found on the Witwatersrand. Relatively recently geologists have linked this to a massive meteorite that hit the area now known the Vredefort crater 2 billion years ago.

The effect was the same as when a stone is thrown into water and creates ripples. The meteorite hit resulted in a huge crater with ‘ripples’ on the earth’s surface. The area effected was 300km across, with Johannesburg near the outer northern edge.

The Witwatersrand ridge is the edge of the huge basin formed by the meteorite, and it was pushed up – as the final ‘ripple’ – from what used to be a flat water-covered area.

The Witwatersrand rocks consist of several layers of very hard, sediments such as quartzite and banded ironstone, which have been erosion-resistant for two billion years.

Just think: if the meteorite had not pushed up this high altitude ridge – or final ‘ripple’ – from the lake-like area of two billion years ago, it is probable that the gold would have been alluvial, and would have been carried away by streams exiting from the ‘lake’.

By July 1886 the news that Harrison had discovered a major reef, the world’s largest ever gold rush began.

Prospectors from all over the world arrived en masse. They lived in tents on the treeless veld in an area known as Ferreira’s Camp. Speculator Col Ignatius Ferreira, an early arrival, most sensibly had organised an ordered ‘village’ of tents. By August 1886 there were about 3 000 inhabitants.

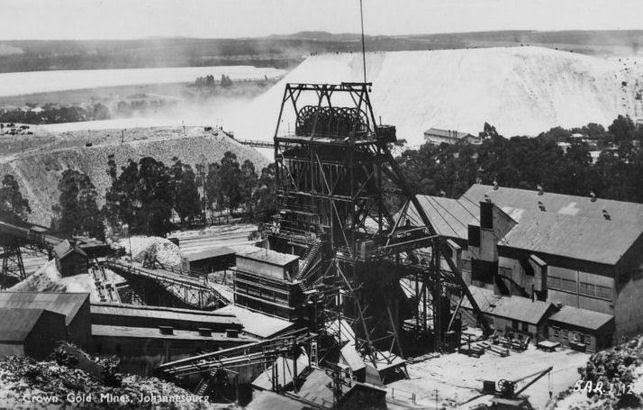

On the 8th of September nine farms in the area were proclaimed public diggings. The Kimberley diamond magnates – who were largely British – were also keenly following developments. When the mines proved to slope downwards – as does the side of a ripple – their wealth enabled them to buy and consolidate the smaller gold mines, and to provide the necessary equipment for deep level mining.

One of the first mines was Ferreira’s. Due to various problems it closed and in the building boom of early Johannesburg it disappeared and was completely forgotten.

In the early 1980s the Standard Bank, which had initially operated in a tent in Ferreira’s Camp in 1886, decided to build new Head Quarters on the southern side of central Johannesburg, in Simmonds Street.

In 1986 when the three stories deep foundations were being prepared, a buried gold mine entrance, or stope, was discovered. It clearly was the entrance to an early gold mine. Research indicated that it was probably Ferreira’s mine of 1886. The stope was preserved and the surrounding area turned into a museum featuring the mining activities of the 1880s. What a coincidence!

As the number of arrivals increased, a name and governmental organisation became necessary, and a town was laid out in late 1886.

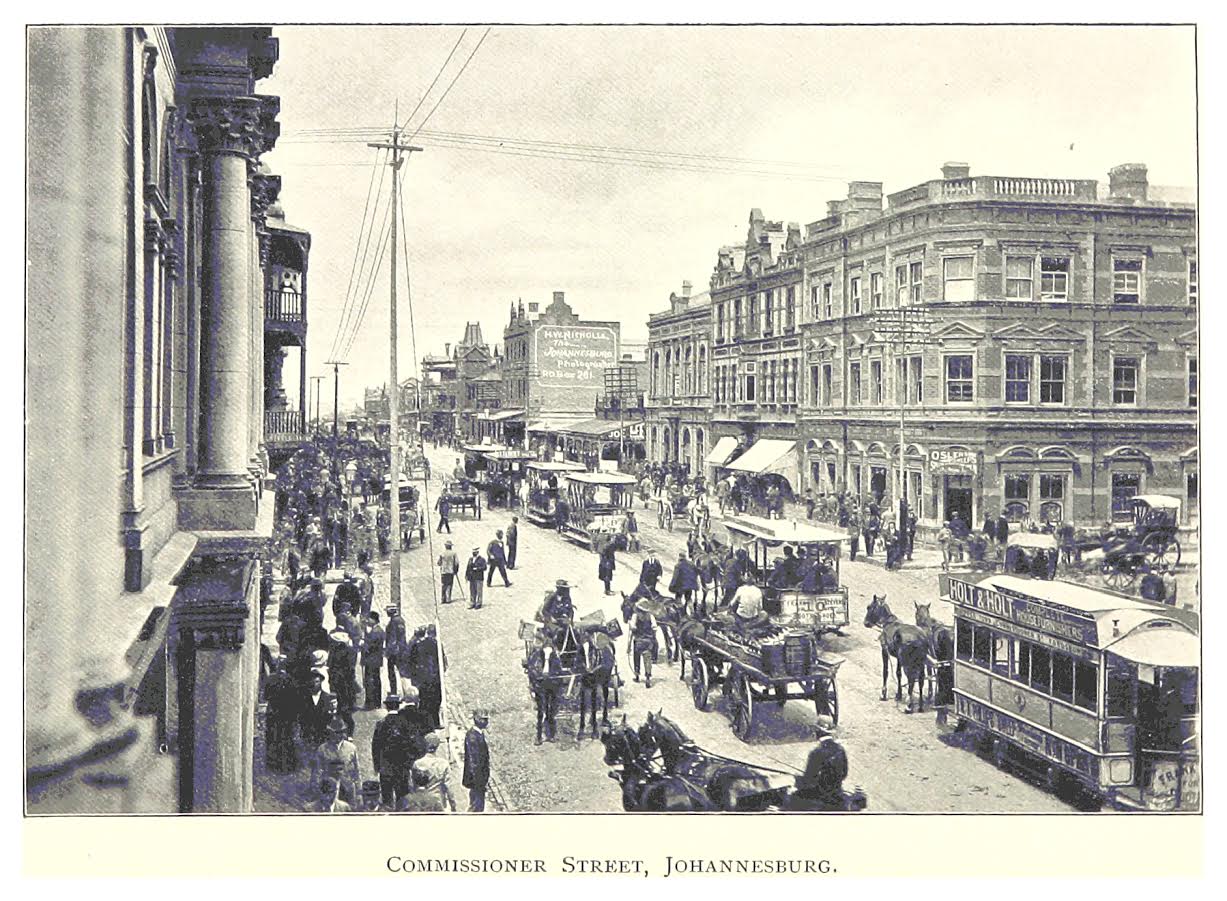

The first auction of stands took place on 8 December 1886. The ZAR government did not believe that the gold would last for long, and so mapped out a small triangular piece of land and crammed in as many plots as possible.

This is the reason why Johannesburg’s streets are so narrow compared to those in most of the old ZAR towns.

Within 10 years, the town was the largest in South Africa, and the number of immigrants was about double the Boer population.

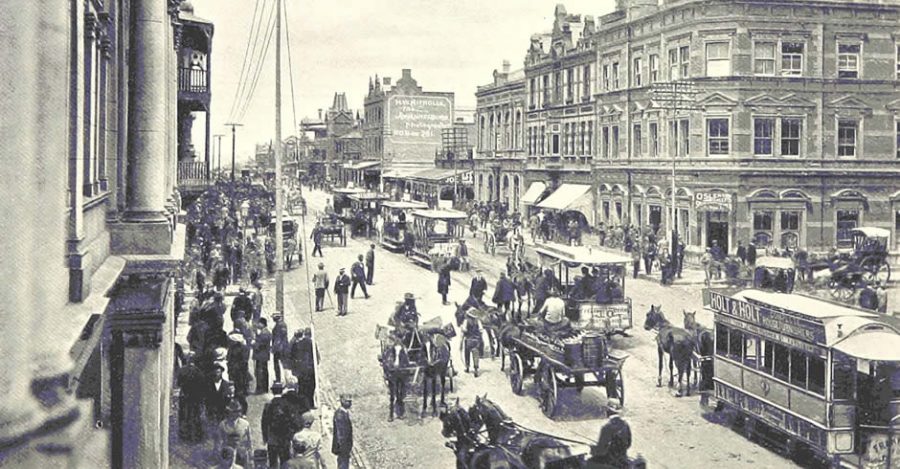

The tented village gave way to corrugated iron structures imported from England and then by brick-and-mortar buildings two to three stories high. There was a daily newspaper, a public library, horse-drawn trams, a train station, an Anglican cathedral, two theatres and a prison.

When elevators became available circa 1930 and more space was needed in central Johannesburg for businesses and professionals, the ‘old’ buildings were knocked down and plots amalgamated to make space for bigger and taller buildings. The era of the ‘skyscraper’ had begun. The ultimate was the Carlton Centre, opened in 1973, with 50 floors.

Where does the name of this now huge city come from? Believe it or not, the precise records for the choice of name were lost!

One has to remember that the government thought that the gold rush would soon be over, so keeping careful records was not important. Another theory is that the surveyors lived in tents, and the papers were blown away one windy day!

Johannes was a common first name in ZAR; it is thought that two surveyors, both with the first name Johannes, chose the name.

The Randlords…

The men who made fortunes from gold mining were known as ‘The Randlords’. To get away from the dusty mining areas just south of the city they moved to the north to the top of the ridge, and built mansions with magnificent views. They named this area ‘Parktown’.

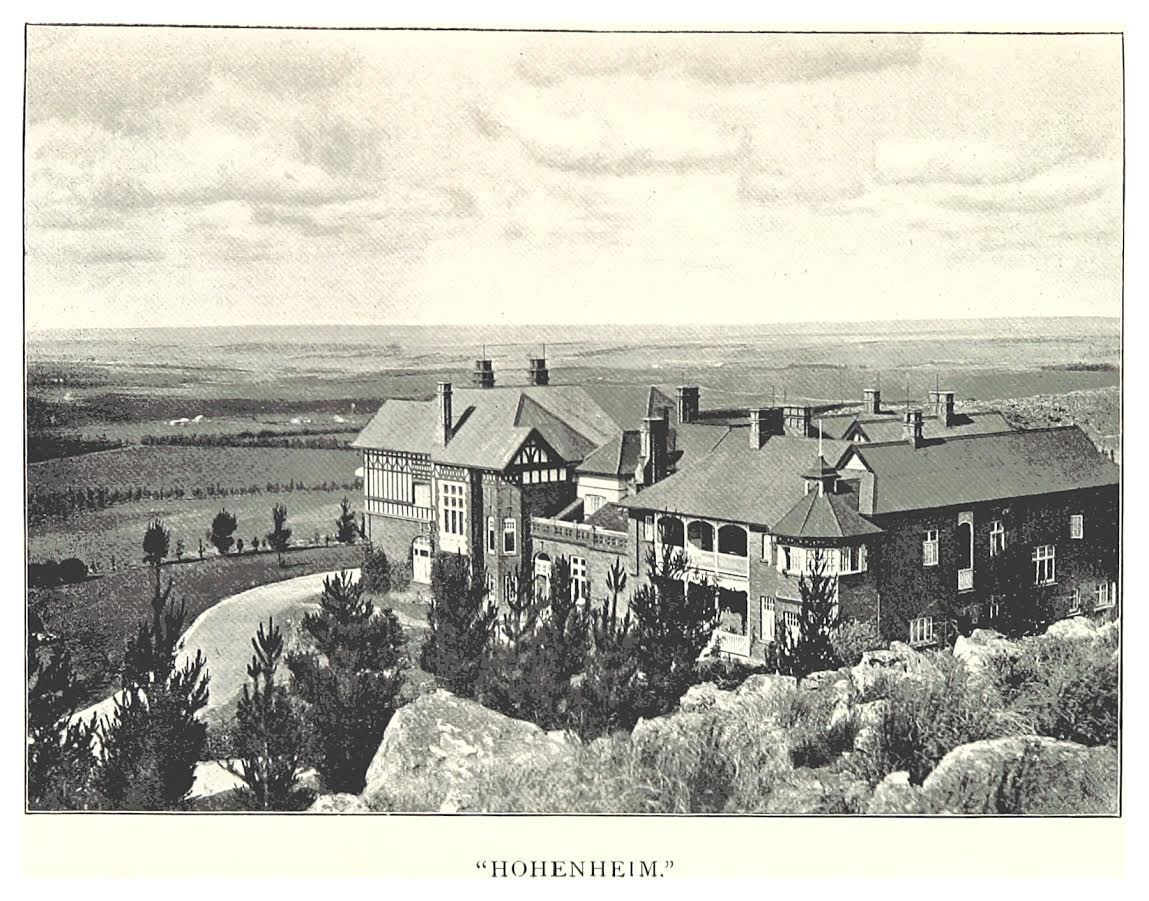

These homes had a magnificent view to the north from their position at the top of the ridge. The first of these mansions, Hohenheim, the home to Sir Lionel Philips and his wife Lady Florence Phillips, was built in 1892, a mere six years after Johannesburg was named. Such was Sir Lionel’s confidence in the Witwatersrand gold reef!

Many of these magnificent homes were later destroyed in the 1970s to make way for a new General Hospital, a new College of Education and the M1 motorway, as well as office blocks, all examples of the needs of a city that has never stopped growing.

Building large homes in Westcliffe soon followed, with many designed by the renowned architect Herbert Baker. His most famous building in South Africa is the Union Buildings in Pretoria.

Fortunately most of the Westcliffe houses are still intact, but with the once huge gardens now much reduced in size. The original gardens of both suburbs were huge, and extended down the steep slope of the ridge.

One can only admire the owners who changed the treeless and rocky grounds into beautiful spaces. Plants from countries with limited rainfall, like Johannesburg, were imported. Some examples are gum trees, jacarandas and wattles. Today, in satellite images, Johannesburg is said to resemble forest.

Nowadays an ever-increasing population has resulted in high density housing with limited space for trees. There is also huge governmental concern about ‘invasive alien plants’ that take over natural habitats and invade water courses.

Many of these ‘aliens’ are the plants that were brought in from elsewhere over 100 years ago because of their attractiveness and climatic suitability! Only relatively recently have indigenous plants become popular.

The Randlords, industrialists and property developers were most generous with donations, both monetary and land, to the growing city. Land was donated for the Zoo, the Zoo Lake and The Wilds. The Johannesburg Art Gallery was built and paintings bought. Wits University was given the 200 acre Frankenwald estate. To this day, wealthy Johannesburgers are still known for their generosity.

The Mine Labourers…

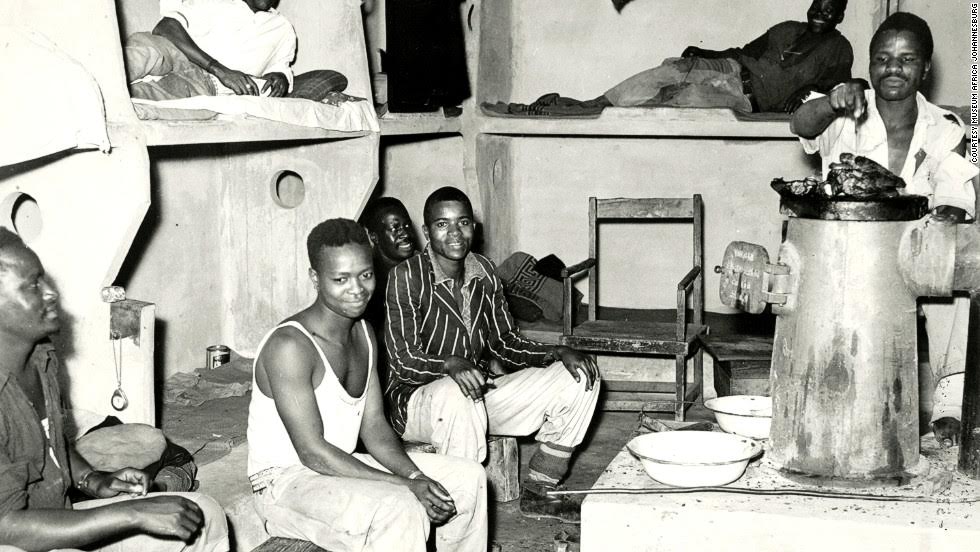

On the other end of the spectrum were mine labourers who lived in appalling conditions. These men – from South Arica, Lesotho, Zimbabwe, Botswana and Mozambique – came to Johannesburg to make money to send home.

They were accommodated in compounds next to each mine. There they found themselves virtual prisoners, because the compound system imposed almost total control over them.

The early compounds were usually wood and iron shacks. They were badly built, often with no windows. Cracks in the walls were stuffed with rags to keep out the wind and the cold. The only heating came from an ‘imbandla’, a big tin of hot coal giving off highly dangerous smoke fumes.

Living conditions were overcrowded, dirty and unhealthy. Inspectors reported that the compound huts contained 20 to 50 workers, who slept on concrete bunks built one above the other like shelves. There was no place for a worker’s possessions. Clothes, bicycles other belongings hung from the ceiling and people could only hope that these would not get stolen. In time, accommodation conditions did improve somewhat.

The Working Class, Professionals and Business Owners…

In between these two extremes, were the working class, professionals and business owners. The earliest suburbs, Newtown, Fordsburg, Jeppestown, Doornfontein and Braamfontein, were all laid out by 1890.

The first two were next to the mines and white working-class families settled there. Doornfontein was a ‘classy’ suburb, where professional and commercial men lived. White wage earners with families and single white men lived in Bertrams and Braamfontein.

The ‘Uitlanders’ (Foreigners)…

By about 1890 the population of the immigrants was thought to be double the Boer population. The ZAR government feared that granting the largely British ‘uitlanders’ – foreigners – the right to vote would lead to the loss of the ZAR’s independence and an annexation by Britain.

In order to prevent this from happening, the government passed legislation refusing voting rights or citizenship to any uitlander who had not been resident for fourteen years and who was over 40 years of age.

This successfully disenfranchised the uitlanders from any political role. Simultaneously the large tax on gold enabled the ZAR to stock pile weapons of war.

As the value of control of the gold mines increased, tensions between the Boers and the British were magnified.

The botched Jamieson Raid of 1895 was the first attempt by the British to take over the ZAR. The horrific Anglo-Boer War of 1899 to 1902 followed. The British won. When the Treaty of Vereeniging was signed on 31 May 1902 the Zuid Afrikaanse Republiek ceased to exist, and all of South Africa became part of the British Empire.

One can only wonder what course history would have taken if the world’s richest gold fields had never been discovered.

Written by: Beverley Ballard-Tremeer who was born and grew up in Johannesburg.