Freedom Day was a long time coming

Freedom Day on 27 April marks the day South Africa voted in its first democratic elections. That day took 342 years to reach. Racial discrimination existed in various forms almost from the start of European settlement in the country, when the Dutch East India Company governor, Jan van Riebeeck, arrived at the Cape in 1652. […]

Freedom Day on 27 April marks the day South Africa voted in its first democratic elections. That day took 342 years to reach.

Racial discrimination existed in various forms almost from the start of European settlement in the country, when the Dutch East India Company governor, Jan van Riebeeck, arrived at the Cape in 1652. But it was formally legislated when the National Party came to power in 1948. Dehumanising laws separating people along race lines, decreeing where they could live, get jobs, educate their children, spend their leisure time, make friendships, were introduced.

(Images: Lucille Davie)

It took 46 years to abandon apartheid, and on 27 April 1994 the first democratic elections were held in the country, with Nelson Mandela becoming the country’s first democratic president. But that was a battle hard fought, with many lives lost, many going into exile, many tortured for their beliefs, many families separated, many lives destroyed. The path to the end of apartheid is a story of courage, determination and sacrifice. Names like Chief Albert Luthuli, Mandela, Oliver Tambo, Walter Sisulu, Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, Helen Joseph, Ruth First, Dr Yusuf Dadoo, Lilian Ngoyi and many others, stand as giants of the struggle.

The Freedom Charter

South Africa’s constitution used the Freedom Charter as its building block. The charter brought together the heartfelt desires and longings of the millions of oppressed South Africans, from all walks of life. On 26 June 1955, people from around the country gathered on a dusty soccer field in Kliptown, the first suburb of Soweto, to approve the Freedom Charter over a two-day period, in an atmosphere described by Mandela in his Long Walk to Freedom autobiography as “serious and festive”.

Mandela set the scene on the day: “More than three thousand delegates braved police intimidation to assemble and approve the final document. They came by car, bus, truck and foot. Although the overwhelming number of delegates were black, there were more than three hundred Indians, two hundred coloureds and one hundred whites.”

On the afternoon of the second day, the police stopped the meeting, saying they suspected treason was being committed. Mandela had to creep away (he and Sisulu were hiding on the roof of a hardware store overlooking the field, because they were banned at the time). He says in his autobiography: “Like other enduring political documents, such as the American Declaration of Independence, the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Communist Manifesto, the Freedom Charter is a mixture of practical goals and poetic language.”

The charter was signed by Luthuli a year later.

The Treason Trial

Mandela admits that the apartheid government had just cause to consider the document treasonable: “The charter was in fact a revolutionary document precisely because the changes it envisioned could not be achieved without radically altering the economic and political structure of South Africa. It was not meant to be capitalist or socialist but a melding together of the people’s demands to end the oppression. In South Africa, merely to achieve fairness, one had to destroy apartheid itself, for it was the very embodiment of injustice.”

And the government acted accordingly. Exactly 18 months later it struck: in December 1956 they arrested Mandela, the entire executive leadership of the ANC and others – 156 people in all. They were charged with high treason and “a countrywide conspiracy to use violence to overthrow the present government and replace it with a communist state”, says Mandela. If found guilty, the sentence was death.

So began the notorious Treason Trial, which lasted almost five years, after which the accused were acquitted – the judges said the prosecution had failed to prove that the ANC was a communist organisation or that the Freedom Charter propagated a communist state.

Of his acquittal in 1961, Mandela said: “After more than four years in court and dozens of prosecutors, thousands of documents and tens of thousands of pages of testimony, the state had failed in its mission. The verdict was an embarrassment to the government, both at home and abroad. Yet the result only made the state more bitter towards us. The lesson they took away was not that we had legitimate grievances but that they needed to be far more ruthless.”

Kliptown Museum

The story of the thousands of people who contributed to the drafting of the Freedom Charter is now told in the Kliptown Open Air Museum. The museum, on the western wing of the Walter Sisulu Square of Dedication in Kliptown, which incorporates the humble soccer field, was opened in 2007.

The museum is open seven days a week, and guided tours are offered.

Liliesleaf in Rivonia

In 1961 the ANC, established in 1912, decided to form an armed wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe (meaning spear of the nation) or MK, led by Mandela. Decades of peaceful resistance had led nowhere, with black people becoming increasingly frustrated. MK’s operations were conducted underground, with its headquarters on a smallholding on a small farm called Liliesleaf, in the suburb of Rivonia, in northern Johannesburg.

The key leaders had operated from its outhouses for two years. Mandela lived on the property, masquerading as the gardener and cook, under the alias of David Motsamayi. In those days, Rivonia consisted of a rural patchwork of smallholdings, riding schools and farms, with few tarred roads. Today, it has been engulfed by the northern expansion of Johannesburg, to become one of the city’s most upmarket suburbs.

In July 1963, a dry cleaning van drove up to the door. Armed policemen burst out … and from that moment, the word “Rivonia” became synonymous around the world with the silencing of black resistance in South Africa. Mandela describes the swoop on Liliesleaf in his autobiography: “On the afternoon of 11 July, a dry cleaner’s van entered the long driveway of the farm. No one at Liliesleaf had ordered a delivery. The vehicle was stopped by a young African guard, but he was overwhelmed when dozens of armed policemen and several police dogs sprang from the vehicle. In the [the thatched cottage] they found a dozen men around a table discussing a document.”

That document turned out to be the plan and outline of Operation Mayibuye, the MK strategy for guerrilla warfare in South Africa. The men in the room were Raymond Mhlaba, Govan Mbeki, Lionel “Rusty” Bernstein, Walter Sisulu, Bob Hepple, Ahmed Kathrada and Denis Goldberg. Mandela himself was absent – he was serving a five-year sentence on Robben Island for inciting workers to strike in mid-1961, and for leaving the country without a passport.

He wrote: “In one fell swoop, the police had captured the entire High Command of Umkhonto we Sizwe.”

Mandela was brought up to Pretoria from the island, having served nine months of his five-year sentence, and together with the other top MK members, was charged with sabotage, a crime carrying the death sentence, in what was referred to as the Rivonia Trial. Says Mandela: “From that moment on we lived in the shadow of the gallows.”

But they didn’t get the death sentence – instead, they were given life imprisonment. In 1964, the prison doors slammed on their backs – most of the men served between 22 and 27 years in prison, Mandela being the last one to be released in February 1990.

At the trial Mandela made a speech from the dock instead of testifying. The speech is perhaps one of the country’s most significant documents, and it ends with probably Mandela’s most poignant words. “During my lifetime I have dedicated myself to this struggle of the African people. I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.”

The buildings of Liliesleaf have been sensitively restored, and are now open as a museum and conference centre. Daily tours can be taken, and the site is open seven days a week.

Resistance gathers

The apartheid government thought it had silenced the ANC, but it wasn’t long before the resistance gathered again. It came to a head with the actions of schoolchildren in Soweto, the country’s biggest township, just outside Johannesburg. There had been rumblings of discontent in early 1976 when the government imposed Afrikaans on pupils, forcing teachers to teach certain subjects in the language of the government, a language with which they were not comfortable.

That discontent culminated in a march by some 15 000 children to the Orlando Stadium in Soweto, on 16 June 1976. But they didn’t get to the stadium because they met the police along the way. With varying accounts of how the bloodshed started, the police were soon firing into the crowd, killing and wounding the children. It is estimated that 566 people died in Soweto on that day.

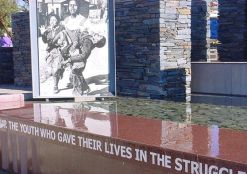

One child, 12-year-old Hector Pieterson, came to symbolise the day and the brutality of apartheid. He was shot by police, and was gathered up in the arms of another pupil, Mbuyisa Makhubo, who, together with Hector’s sister, Antoinette, ran towards a press car, where he was bundled in, and taken to a nearby clinic, where he was pronounced dead.

Another child, 13-year-old Hastings Ndlovu, was fatally shot before Hector was gunned down, but the difference was that photographer Sam Nzima was on hand to record the event, in what is now an iconic image of apartheid police killing children. The photograph hit the front pages of the world’s newspapers the next day.

“I saw a child fall down. Under a shower of bullets I rushed forward and went for the picture. It had been a peaceful march, the children were told to disperse, they started singing Nkosi Sikelele [the freedom anthem]. The police were ordered to shoot,” said Nzima of the day. “I was the only photographer there at the time. Other photographers came when they heard shots,” he says. Nzima was a photographer for The World newspaper in Johannesburg.

The Hector Pieterson Museum and Memorial, opened in 2002, commemorates Hector and the other children who died on that day and the days that followed. The confrontation spread around the township, and around the country, and 16 June, now commemorated as Youth Day, will forever be remembered as the day of the beginning of the end of apartheid.

It was followed by the turbulent 1980s, when apartheid’s cracks widened, aided by international boycotts and sanctions and the unsustainability of apartheid. By the end of the 1980s, apartheid was on its knees, a wounded and desperate animal. In February 1990, Mandela was released from prison and four years later the first democratic elections were held.

The Apartheid Museum, in Nasrec in southern Johannesburg, graphically and movingly captures the terrible history of apartheid, in powerful displays, large blown-up photographs, artefacts, newspaper clippings, and some moving film footage. This extraordinarily powerful museum is an obligatory stop for tourists and residents alike.

By: Lucille Davie

Source: www.mediaclubsouthafrica.com