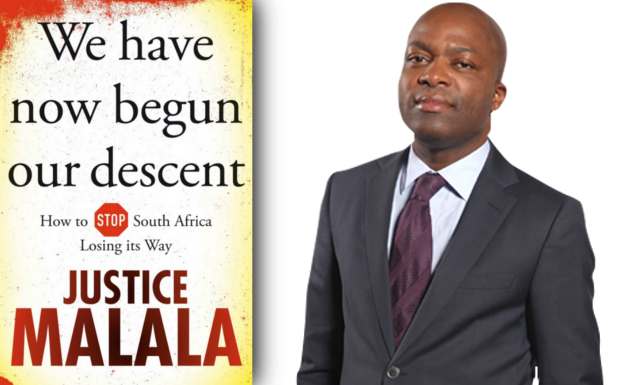

Justice Malala Puts SA’s Deepening Malaise in Plain Language

Justice Malala’s book, “We Have Now Begun Our Descent: How to Stop South Africa Losing its Way”, does a number of things well. It reclaims the space for a particular kind of conversation among successful but ordinary South Africans – those who are not radical or particularly steeped in the eloquent and sometimes exclusionary new […]

Justice Malala’s book, “We Have Now Begun Our Descent: How to Stop South Africa Losing its Way”, does a number of things well. It reclaims the space for a particular kind of conversation among successful but ordinary South Africans – those who are not radical or particularly steeped in the eloquent and sometimes exclusionary new language of radical opposition to structural inequality.

While the book covers some well-trodden ground, Malala writes in an accessible style and with a common-sense decency and rationalism that many people will find compelling.

Malala puts forward the thesis that South Africa faces a crisis of governance and leadership rather than an economic crisis. He argues that addressing the leadership crisis is not something that the African National Congress is responsible for alone: South Africans have a role to play and yet they have simply not done enough to challenge the status quo.

Malala is a popular and trusted figure on the South African political landscape. He is cosmopolitan and well travelled and so whites generally like him. At the same time, because of his humble roots and straight talk, Malala also appeals to many in the black middle class.

In many ways, then, this book presents an opportunity for Malala to explicitly locate himself as a moderate; as someone capable of addressing the complex and deeply divisive socioeconomic and political challenges confronting South Africa today.

Centring the book around the claiming of this moniker as an identity would have allowed him to talk the reader through his assumptions and expand on the politics of moderation at a time when this is sorely needed. It would have also given the book a post-Rainbow philosophical grounding and forced Malala to tease out a range of arguments that need unpacking in contemporary South Africa.

The thorny issue of constitutionalism

There are three issues that deserve deeper attention than Malala gives them. The first relates to the South African Constitution; the second is about race and the last concerns the economy.

Like Malala, I lean in favour of South Africa’s Constitution and of constitutionalism. Time and again he returns to the tenets and founding principles that guided the development of the constitution, reminding the reader that the ANC has an imperative to lead the nation according to its values.

Yet there have been a range of critiques from across the political spectrum about the limits of liberalism, and the extent to which some forms of land redistribution are off the table because property rights are so firmly entrenched in the Constitution. While there are many South Africans who would welcome a non-polemical discussion about constiutionalism and the rule of law, Malala doesn’t allow us to air this conversation.

Similarly, the chapter on race never really takes off. It is as though Malala is reluctant to say too much. He concedes that there is pain, and that there has not been enough change. Oddly though, he concludes that, “growing the economy” is the silver bullet for our racial problems.

This broad statement doesn’t address the casual racism experienced by middle class black people. Nor does it examine the increasing animosity between black South Africans who feel frustrated and whites who think the ANC is reneging on its promises of non-racialism. These issues lie at the heart of the combustible racial climate of the moment. Yet Malala leaves them be.

When it comes to the economy Malala endorses the National Development Plan. But he doesn’t talk about the important leftist critique that it represents an orthodox and unimaginative economic model. In other words, Malala doesn’t adequately look at the big policy debates and how they connect with poor leadership.

Beyond party politics and macho orthodoxy

Malala suggests that South Africans deserve their leaders because they haven’t done anything to challenge them. Yet he never takes this idea outside the political arena.

From his perch as a moderate, I wanted Malala to nudge the reader in the direction of the kinds of community structures (like churches and schools) that shaped his early years. I wanted him to examine the student movement that had already begun by the time he wrapped up the book and assess civil society potential to grow leaders.

On the other hand, given the macho nature of current-day political discourse, I was pleased to see Malala embrace vulnerability as a form of courage. I was fascinated by the section of the book where he details his shame at keeping quiet when two executives were censured by eNCA, a private broadcaster, after revelations that they had succumbed to pressure from senior ANC officials to cover government stories in a positive light.

“I should have made it clear that I disagreed, that requests of this nature … were really what happens at the start of dictatorship … I was one among the many who kept quiet…”

This statement lays bare the complicated ways in which Malala suggests we are all complicit in upholding the hegemony of the ANC. It has the power to occupy the heart of the book, and yet Malala never fully explores his silence.

I wanted Malala to reflect more deeply on why he kept quiet in that instance when he has spoken out on so many other difficult issues. This is especially the case because I can think of few black political observers more qualified than Malala to help us understand the risks and rewards of silence, and the calculations that go into deciding if and whether and when to speak.

While Malala does not claim the title of a moderate, I think he deserves it. At a time when we need voices that are committed to bridging divides and enhancing dialogue, Malala occupies a unique and important place in South African society. Like all political talk show hosts (which is what he does best), Malala needs the country to both trust him and to grapple alongside him.

This book marks an important step in doing this. In it, we see Malala vulnerable and nostalgic and deeply committed to looking at the country’s flaws with love and respect. I look forward to reading more from him as he continues to claim and broaden the middle way.

“We Have Now Begun our Descent: How to Stop South Africa Losing its Way” by Justice Malala is published by Jonathan Ball Publishers, 2015.![]()

Sisonke Msimang is a Ruth First Fellow in Journalism at the University of the Witwatersrand. This article was originally published in The Conversation. Read the original article.