South African Crime Stats Show Police Struggling to Close Cases

South Africa’s latest crime statistics released by the country’s police service reflect a continued long-term decline in levels of non-violent property crime, a possible stabilisation following four years of increase in murder, and a sustained rise in violent property crime. More worryingly, a closer look at case outcomes points to the toll that the leadership […]

South Africa’s latest crime statistics released by the country’s police service reflect a continued long-term decline in levels of non-violent property crime, a possible stabilisation following four years of increase in murder, and a sustained rise in violent property crime.

More worryingly, a closer look at case outcomes points to the toll that the leadership crisis in crime intelligence and the struggling detective service are beginning to take on investigative capacity.

Each of the last four national police commissioners has been removed on suspicion of corruption or being otherwise unfit for office. These and other senior criminal justice system appointments are now widely seen as sites of factional disputes within the ruling African National Congress (ANC), or as attempts by the powerful to avoid facing criminal responsibility for their actions.

Some commentators, such as the Institute for Security Studies and Corruption Watch, are increasingly concerned that the series of poor appointments and lack of leadership stability are having a direct impact on crime levels.

I believe that changing socioeconomic conditions are likelier culprits. There is undoubtedly a relationship between economic deprivation and crime, although the exact nature of the relationship is a matter of endless debate. It would be surprising if South Africa’s increase in poverty since 2011 were not putting upward pressure on violent crime.

Whether or not police leadership can have a real impact on crime levels, they do affect the services delivered to victims.

Justice increasingly delayed

In the last five years, the number of cases of aggravated robbery recorded by the police rose by almost 40%. Meanwhile the number of convictions for aggravated robbery rose by just 5%.

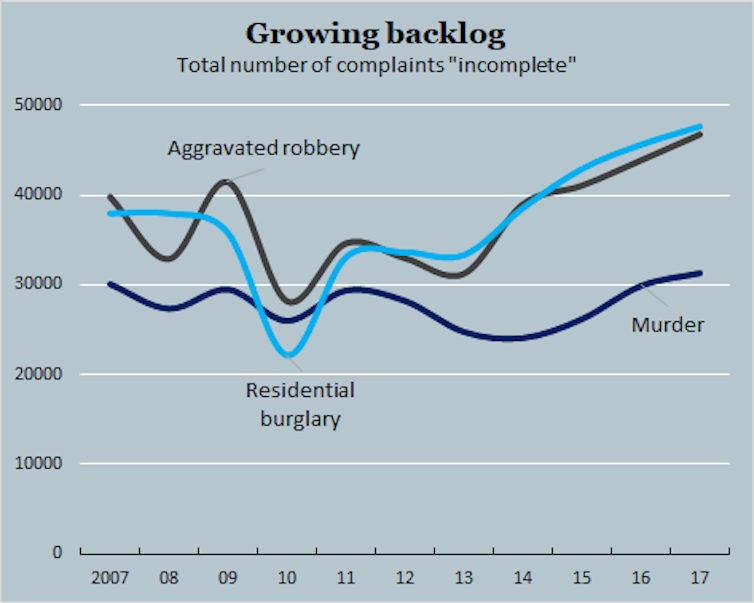

The number of cases in which investigation has not been finalised is also showing worrying trends. “Incomplete” murder and residential burglary complaints are at 10 year highs. Despite the declining total volume of crime reported to the police, the investigative backlog is growing.

This is a sign of justice increasingly delayed and possibly denied.

It’s also a sign of an organisation struggling to meet demand for its services.

The new police minister, Fikile Mbalula, must work to rapidly improve investigative performance. To the extent that the police can be expected to prevent crime, their chief strategy should be solving cases. If they can’t do that, they have little hope of stemming the robbery tide.

Limits to the data

The South African Police Service crime statistics are a rich source of knowledge about the crime situation in the country. But they need to be handled with care. This means remembering at least three things.

First, not all crimes are reported to the police, or recorded by them. This means that the official figures are an under-count. The extent of this varies by crime type. For example, we know from surveys that sexual offences are rarely reported, while vehicle thefts are almost invariably reported.

Second, some victims and communities are more likely to report to police, and they’re more likely to be taken seriously by the police. For example, recent survey data shows that white South Africans are far more likely to report a theft to the police and to be satisfied by the police response to their burglary than other population groups. They are also more likely to be insured, which is a key determinant of reporting of crimes like vehicle theft.

This means that a theft in a largely white, relatively prosperous area is considerably more likely to make it into the official police stats than a theft in an area dominated by other population groups, where satisfaction with police performance is lower, and where few have the incentive of claiming from insurance.

Third, crime statistics always need to be read in the context of other available data. Statistics South Africa’s annual Victims of Crime Survey is an essential companion document to the crime statistics, providing some of the necessary context on just how partial and distorted the official figures are.

The stats in brief

Declines have continued in most non-violent property crimes like burglary and vehicle theft. These trends are supported by data from the Victims of Crime Survey. They are noteworthy, given that non-violent property crimes still constitute the bulk of crime in the country.

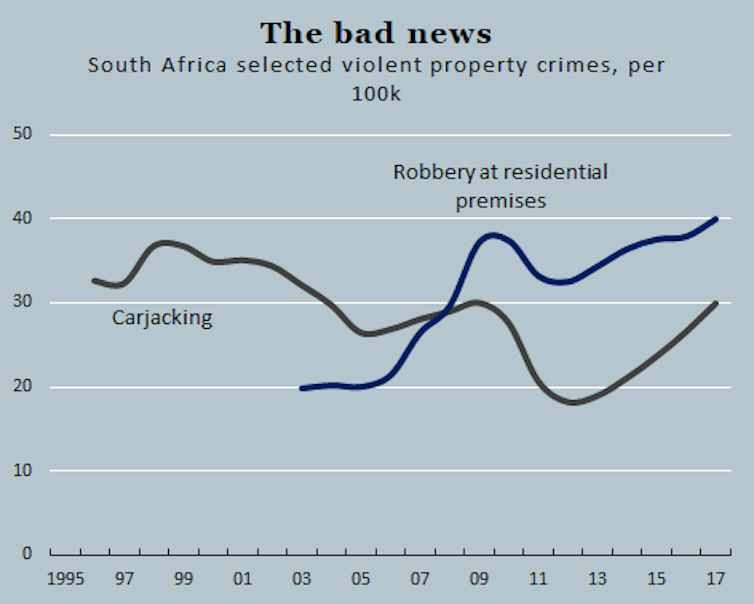

On the other hand, the violent property crime situation continues to show serious deterioration. Aggravated robberies have risen by almost 30% in the last five years. Rates of carjacking have increased by about 13% in the last year alone. They are at risk of reclaiming the heights last seen in the late 1990s. House robbery rates have doubled since 2003.

So, although the average person in South Africa is increasingly unlikely to lose their property to crime, the crime they experience is increasingly likely to involve physical, sometimes violent interaction with criminals.

Although murder figures increased by about 1.8% in the last year, in the same time the national population increased by about 1.7%. The murder rate per capita thus saw no significant change. This possible stabilisation is an improvement on the marked increases of the previous four years, but falls short of the decline needed to return the country to a longer positive trajectory.

![]() This is sorely necessary, given that someone in the country is murdered about every 28 minutes.

This is sorely necessary, given that someone in the country is murdered about every 28 minutes.

Anine Kriegler, Researcher and Doctoral Candidate in Criminology, University of Cape Town

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.