Sinking an Economy without Water by 2035

Dire economic destabilisation, a disenfranchised populace and death – these are not the results of spiraling crime figures or rampant political corruption, but of another, more insidious threat to South Africa’s national security. These are the very likely consequences of a continued disregard for the country’s most valuable resource: water. (See infographic below.) The most […]

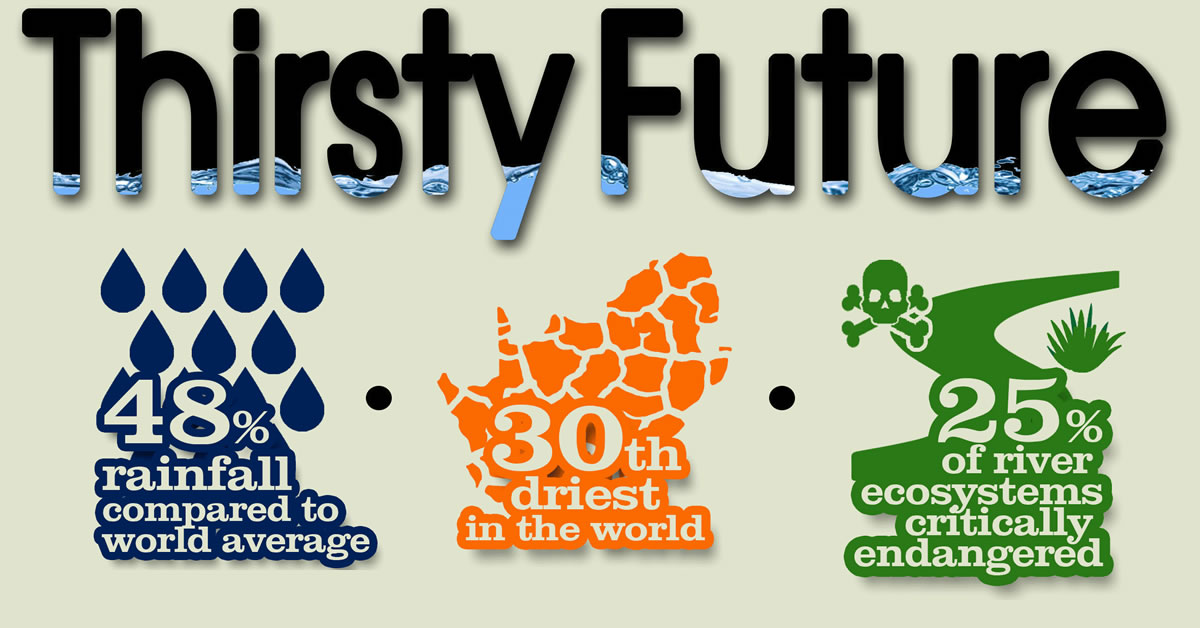

Dire economic destabilisation, a disenfranchised populace and death – these are not the results of spiraling crime figures or rampant political corruption, but of another, more insidious threat to South Africa’s national security. These are the very likely consequences of a continued disregard for the country’s most valuable resource: water. (See infographic below.)

The most recent spate of droughts across the country has been precipitated by four years of lower than normal rainfall and has placed immense pressures on domestic water provision.

Thus far the water shortages have been blamed on the adverse weather phenomenon known as El Nino, the (Christ) child, named so because of its usual occurrence close to Christmas.

This adolescent saviour has been blamed for all the major South African droughts since the ’90s – 1992/93, 1997/98 and 2001/02 – and the relatively long respite since 2002 was inevitably going to be broken sooner rather than later.

It is easy to blame recurring water shortages on the fickle cycles of weather patterns of the Peruvian coast, but it is wise to remember that South Africa is not naturally abundant with aqua at the best of times.

South Africa remains a water scarce country that only gets about 40% the global average of rainfall per year and is in fact considered to be the 30th driest country in the world.

And yet we have an agricultural sector that is a top ten producer in the world of 8 different crops, including grapefruit (4th largest producer in the world), which is one of the most water intensive crops.

Furthermore, even accounting for the thirst of agriculture, the rest of the country’s parchedness seems unquenchable: the world average daily per capita consumption of water is 173 litres while South Africa’s is a staggering 235 litres – 37% more – in one of the world’s most arid climates.

Projections estimate that by 2035 there will be a 3.2km3 gap between water supply and water demand. That is roughly 1.3 million Olympic sized swimming pools, or about 60% of all water that is currently being used for municipal purposes.

According to South African news sources, a recent government report, as yet unpublished, estimates that R58bn per year is needed over the next 5 years to avert the looming water crises. For 2015 the government only budgeted R2.9bn (5% of what is required) on water infrastructure management.

But it is understandable that it is difficult for a government to justify spending 5% of the entire national budget (R1100bn for 2015) on water infrastructure management when everyday South Africans feel entitled to the water coming out of their taps and don’t necessarily foresee the disastrous long term implications of a prolonged water crisis.

Firstly, it has to be noted that even a water deficit as large as predicted by 2035 will rarely result in any human casualties, at least directly. Even with a 3.2km3 supply and demand discrepancy the country still has enough drinking water for everyone and this will obviously be prioritised by the government in the event of extreme shortages.

The first things to go of course will be the non-essentials – the swimming pools and the immaculate gardens and lawns. Such measure will of course barely impact the majority of South Africans, but non-essential municipal water loads only account for so much of the current water demand.

What will be next to suffer will be either the agricultural (57% of current demand) or industrial (8% of current demand) sectors which will have a major impact on the South African economy: 3.2km³ of water will be almost a third of the estimated agricultural demand in 2035 and little more than the entire estimated industrial demand in that same year.

Either food security or industry will suffer, most likely both, but in every scenario, the South African economy will be much worse off.

What is the government doing to prevent a crisis from happening?

Well it has started initiatives like ‘No Drop’ which aims to reduce the 36.8% of municipal water that is lost through leakages and also formulating a National Water Resource Strategy (which is now in its second iteration) acknowledging addressing the critical artisinal skills shortages in the water sector.

However, South Africa has always been excellent at developing and discussing strategies and plans, but now, more so than ever, it becomes important that they be wisely and effectively implemented in order to avoid a catastrophic economic and social failure in the future.

And it is not only the government that needs to hastily learn to respect South Africa’s most valuable resource, but also its citizens, who individually need to understand that although access to water is still a basic human right enshrined in the wonderful constitution of this country, it can and will only remain so as long as there is still water to be passed around.

And that might very well not be the case in 20 years time.

For more interesting articles and infographics ranging from the SA becoming a Protestnation, despite having far less protests per capita than Switzerland, to a 100 years of movies in Mzanzi, visit safro.info.