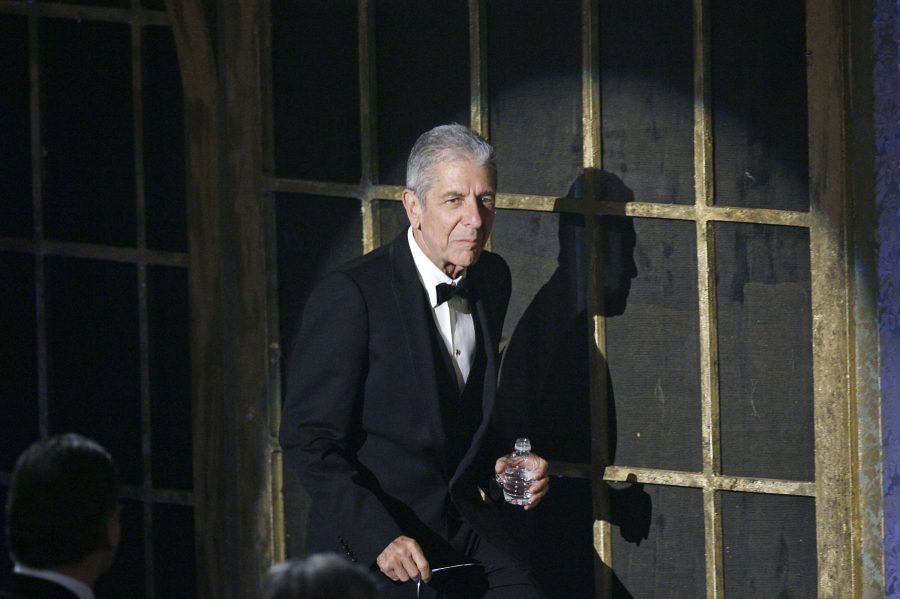

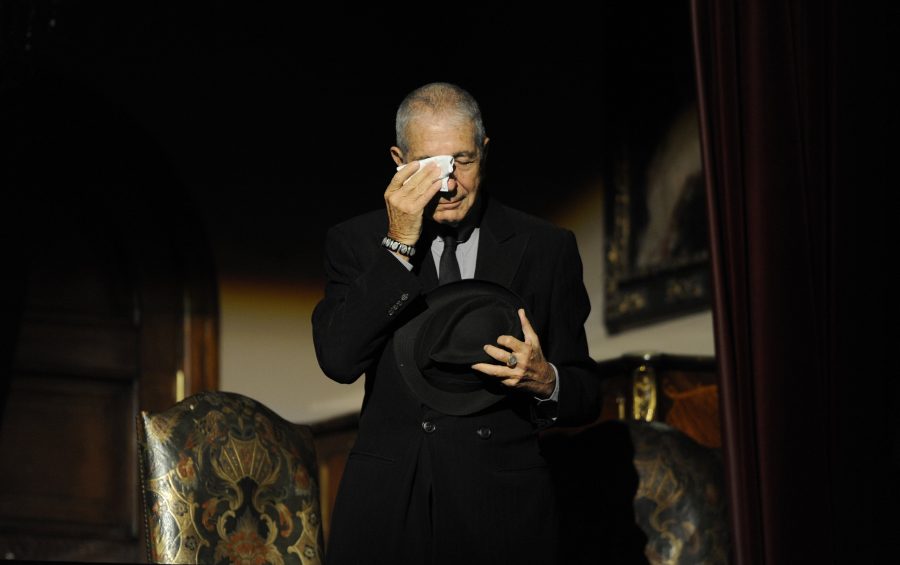

Leonard Cohen, Rock Music’s Poetic Visionary, Dies at Age 82

LOS ANGELES (Reuters) – Leonard Cohen, rock music’s man of letters whose songs fused religious imagery with themes of redemption and sexual desire, earning him critical and popular acclaim, has died at age 82, a statement on his Facebook page said. “It is with profound sorrow we report that legendary poet, songwriter and artist, Leonard […]

LOS ANGELES (Reuters) – Leonard Cohen, rock music’s man of letters whose songs fused religious imagery with themes of redemption and sexual desire, earning him critical and popular acclaim, has died at age 82, a statement on his Facebook page said.

“It is with profound sorrow we report that legendary poet, songwriter and artist, Leonard Cohen has passed away,” a statement on the Facebook page said. “We have lost one of music’s most revered and prolific visionaries.”

The statement did not provide further details on Cohen’s death, and representatives for the singer could not be reached immediately for comment. It said a memorial was planned in Los Angeles, where Cohen had lived for many years.

“R.I.P. Leonard Cohen,” singer-songwriter Carole King said on Twitter.

Singer Roseanne Cash echoed the lyrics from Cohen’s song “Anthem” when she said in a tweet: “Leonard Cohen is dead. There’s a crack in everything. No light yet.”

Cohen, a native of Quebec, was already a celebrated poet and novelist when he moved to New York in 1966 at age 31 to break into the music business.

Before long, critics were comparing him to Bob Dylan for the lyrical force of his songwriting.

Although he influenced many musicians and won many honours, including induction into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame and the Order of Canada, Cohen rarely made the pop music charts with his sometimes moody folk-rock.

But Cohen’s most famous song, “Hallelujah,” in which he invoked the biblical King David and drew parallels between physical love and a desire for spiritual connection, has been covered hundreds of times since he released it in 1984.

“Hallelujah’s” long road to mass appeal was matched by Cohen’s own painstaking approach to writing it. He spent five years penning drafts, at one point banging his head on the floor of a hotel room in frustration.

Watch video of Leanard Cohen’s Hallelujah.

THE SACRED AND PROFANE

Many of Cohen’s songs became hits for other artists, including Judy Collins, who helped Cohen gain fame by recording some of his early compositions in the 1960s.

Cohen’s most ardent admirers compared his works to spiritual prophecy. He sang about religion, with references to Jesus Christ and Jewish traditions, as well as love and sex, political upheaval, regret and what he once called the search for “a kind of balance in the chaos of existence.”

His lyrics were deeply personal and at times took on an element of prayer, as in 1969’s “Bird on the Wire” in which he sang: “I swear by this song/And by all that I have done wrong/I will make it all up to thee.”

Cohen’s other well-known songs include “Suzanne,” “So Long, Marianne,” “Famous Blue Raincoat” and “The Future,” an apocalyptic 1992 recording in which he darkly intoned: “I’ve seen the future, brother/It is murder.”

The inspiration for “So Long, Marianne” was Cohen’s longtime romantic partner and muse Marianne Ihlen, a Norwegian woman he met while living on the Greek island of Hydra in the 1960s.

A New Yorker profile of Cohen last month recounted how, after being told in July she had only a few days left to live, he emailed her: “Well Marianne, it’s come to this time when we are really so old and our bodies are falling apart and I think I will follow you very soon. Know that I am so close behind you that if you stretch out your hand, I think you can reach mine.”

Two days later, he learned in an email she had died after reading his note.

Read the full story of the message Leonard Cohen sent to Marianne.

Cohen toured extensively from 2008 to 2013 after being unable to collect most of a $9 million judgment against his former manager and lover, Kelley Lynch, whom he accused of draining his savings.

He released an album, “You Want It Darker,” just last month. But the New Yorker described him as ailing, quoting him as saying he was more or less “confined to barracks” in his Los Angeles residence.

MEANING AMID LOSS

Cohen’s nasal voice and deep-bass, conversational vocals were criticized by some as being monotone. British musician Paul Weller once called his melancholy style “music to slit your wrists to.”

But his work was also suffused with irony and self-deprecating humour, often touching on his relationship with fame and his reputation for romantic entanglements.

“I got this rap as a kind of ladies’ man,” Cohen told Canada’s Globe and Mail in 2007. “And as I say in one of the poems, it has caused me to laugh, when I think of all the lonely nights.”

Born into a Jewish family in 1934 and raised in an affluent English-speaking neighbourhood of Montreal, Cohen read Spanish poet Federico García Lorca as a teenager, learned to play guitar from a flamenco musician and formed a country band called the Buckskin Boys.

He attended McGill University in Montreal and published his first book of poetry shortly after graduation.

Living on grant money from the Canadian government and an inheritance from his family, Cohen published in the 1960s the poetry collections “The Spice-Box of Earth” and “Flowers for Hitler” and novels “The Favourite Game” and “Beautiful Losers.”

But disillusioned with his meagre income, Cohen turned to songwriting and landed an audition in 1967 with John Hammond, the producer who had discovered Dylan. Hammond signed him to Columbia Records, which would remain Cohen’s label for five decades.

Cohen toured widely but also sought solace in meditation, far from the public eye. For part of the 1990s, Cohen lived in a Zen Buddhist monastery in the San Gabriel Mountains just outside Los Angeles, where he handled tasks as menial as cleaning toilets.

Cohen, who never married, is survived by his daughter, Lorca, and his son, Adam.

Watch Leonard Cohen classic song sung in Afrikaans ‘Dans My’, and South African Tribute by Gus Silber

(Additional reporting by Dan Whitcomb; Editing by Peter Cooney and Paul Tait)