African Stillbirth Tragedy – More Than 160 Years to Catch Up

It will take 160 years before a baby in Africa has as much chance of being born alive as a baby in a high-income country, according to new research published today by esteemed medical journal The Lancet. The publication claims 3,287 lives are lost each day due to preventable stillbirths, and that the slow progress on the […]

It will take 160 years before a baby in Africa has as much chance of being born alive as a baby in a high-income country, according to new research published today by esteemed medical journal The Lancet.

The publication claims 3,287 lives are lost each day due to preventable stillbirths, and that the slow progress on the prevention of stillbirth leaves the parents of 2.6 million babies worldwide suffering in silence each year, particularly in Africa.

This, they say, creates an “epidemic of grief” with millions of women living with symptoms of depression following the stillbirth, and many fathers reporting that they suppress their grief. In a graph the Lancet shows how the three most common responses to stillbirth are unhelpful taboos – “It’s probably her diet”, “Demons killed the child” and “Well, then it wasn’t meant to be…”

A mother from Malawi Christina Sapulaye, who experienced a stillbirth last year, says: “It was a very painful situation to me and I never knew what to do… I am being stigmatised by my own people and was divorced due to the stillbirth, and now I am by myself with my little kids.”

In today’s press release the Lancet says its extensive research shows maternal and child deaths have halved while stillbirths (in the third trimester of pregnancy) remains a neglected global epidemic…even though the majority are preventable.

The reports says half of all stillbirths occur during labour and birth, usually after a full nine month pregnancy, and the research highlights that most of these 1.3 million deaths could be prevented with improved quality of care.

Globally, 98% of all stillbirths occur in low- and middle-income countries. The research also reveals that more than 4.2 million women live with depression, often for years, after the stillbirth occurs.

Series co-leader, Professor Joy Lawn from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, said: “We must give a voice to the mothers of 7,200 babies stillborn around the world every day.

“There is a common misperception that many of the deaths are inevitable, but our research shows most stillbirths are preventable.”

She said: “These babies should not be born in silence, their parents should not be grieving in silence, and the international community must break the silence as they have done for maternal and child deaths. The message is loud and clear – shockingly slow progress on stillbirths is unacceptable.”

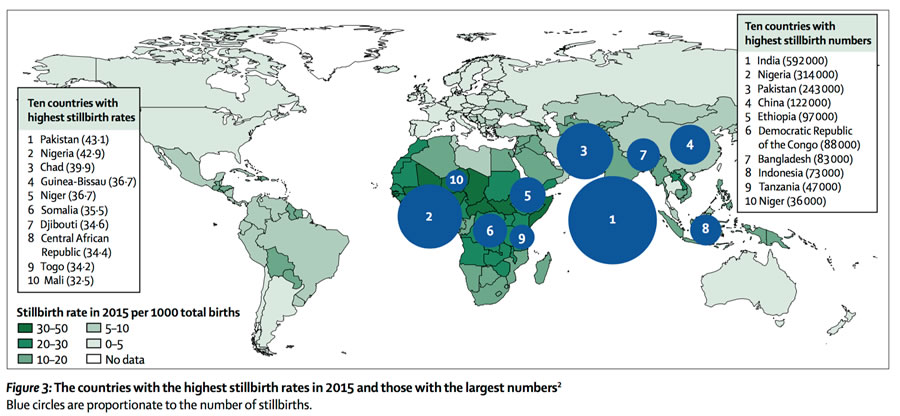

India has the highest number of stillbirths with Pakistan recording the highest rate in the world. Iceland reports the best rate, with the Netherlands making the fastest progress. The US is one of the slowest progressing countries.

In Africa, the rates of stillbirth are highest in Nigeria, with Rwanda outperforming its neighbours as the fastest progressing country in Africa, “demonstrating that most stillbirths are preventable and progress is achievable”.

UN Secretary-General, Ban Ki-moon, said: “Childbirth is one of the most risky moments of life for both mothers and babies. We must make a global push to eliminate the tragedy of the millions of mostly preventable stillbirth deaths that occur every year.”

The new research includes the first global analysis of risk factors associated with stillbirth, and reveals many deaths can be prevented by:

- Treating infections during pregnancy – particularly in sub-Saharan Africa where, for instance, 11.2 % of stillbirths are associated with syphilis.

- Tackling the global epidemics of obesity and non-communicable diseases, notably diabetes and hypertension – at least 10% of all stillbirths are linked to each of these conditions.

- Strengthening access to and quality of family planning services – especially for older and very young women, who are at higher risk of stillbirth.

- Addressing inequalities – in high-income countries, women in the most disadvantaged communities face at least double the risk of stillbirth.

The Lancet says that half of 3,503 parents surveyed in high-income countries felt society wanted them to forget their stillborn baby and try to have another child.

The economic impact of stillbirth for families ranges from funeral costs for their baby to loss of earnings due to time off work, with data suggesting 10% of bereaved parents remain off work for six months. The direct financial cost of stillbirth care is 10-70% greater than for a live birth, with additional costs to governments due to reduced productivity of grieving parents and increased welfare costs.

The Ending Preventable Stillbirth Series was developed by 216 experts from more than 100 organisations in 43 countries and comprises five papers. It follows the research group’s 2011 series on stillbirths also published in The Lancet.

MORE