African Politicans Seeking Medical Help Abroad is Shameful, and Harms Health Care

There is an African idiom that if a man does not eat at home, he may never give his wife enough money to cook a good pot of soup. This might just be true when applied to politicians on the continent seeking medical help anywhere but home. Africa’s public health systems are in a depressing […]

There is an African idiom that if a man does not eat at home, he may never give his wife enough money to cook a good pot of soup. This might just be true when applied to politicians on the continent seeking medical help anywhere but home.

Africa’s public health systems are in a depressing condition. Preventable diseases still kill a large number of women and children, people travel long distances to receive health care, and across the continent patients sleep on hospital floors. On top of this, Africa’s health professionals emigrate in droves to search for greener pastures.

It’s therefore not surprising that people from Africa travel abroad – mainly to Europe, North America and Asia – for their medical needs. In 2016, Africans spent over USD$6 billion on outbound treatment. Nigeria is a major contributor. Its citizens spend over USD$1 billion annually on what’s become known as medical tourism.

It can be argued that private citizens opting to seek medical help in other countries don’t owe the public any explanation, because it’s their own affair. But medical tourism among Africa’s political elite is a completely different kettle of fish and a big cause for concern, because they are responsible for the development of proper health care for the citizens of their countries.

The shame

It’s well documented that politicians from across the continent go abroad for medical treatment. The reasons for exercising this choice are obvious: they lack confidence in the health systems they oversee, and they can afford the trips given that the expenses are paid for by taxpayers.

The result is that they have little motivation to change the status quo. Medical tourism by African leaders and politicians could therefore be one of the salient but overlooked causes of Africa’s poor health systems and infrastructure.

Since the beginning of 2017, President Muhammadu Buhari of Nigeria has spent more time in the UK for medical treatment than he has in his own country. By seeking treatment abroad, Buhari broke one of his own electoral promises – to end medical tourism.

Buhari is just one of many heads of state to find help elsewhere. Patrice Talon, the President of the Republic of Benin, underwent surgery in France a few months ago.

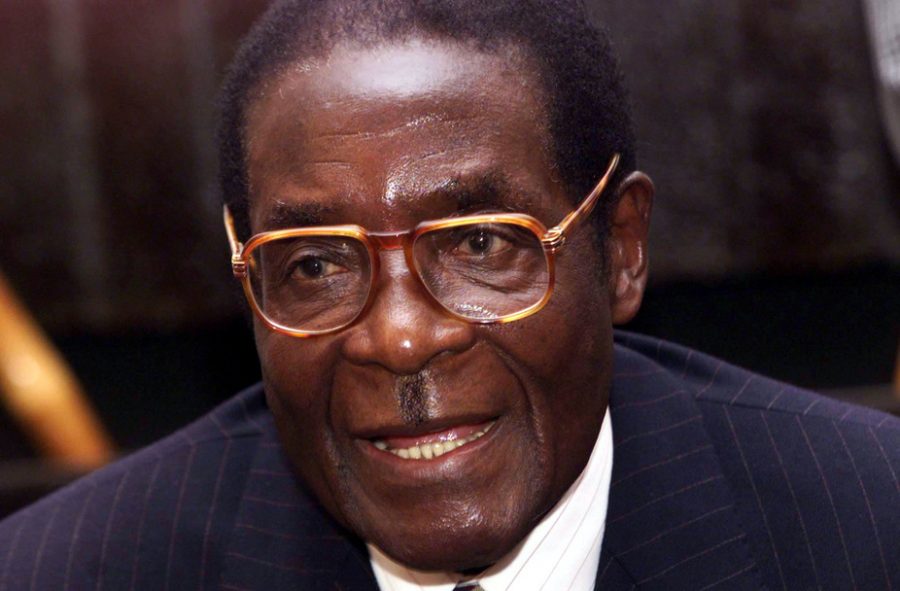

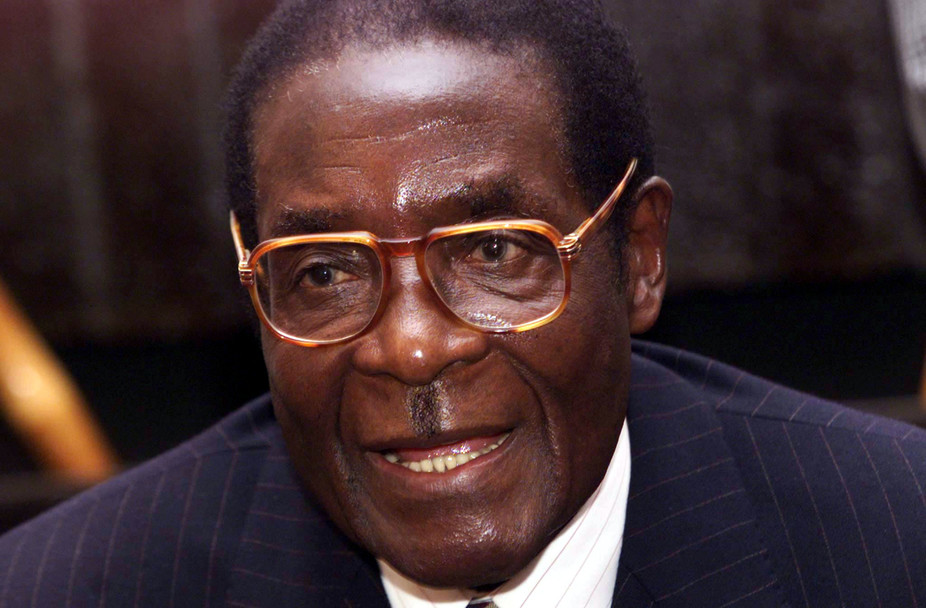

The cases of Buhari and Talon, however, aren’t as bad as other presidents who have had decades to fix their countries’ health care systems, but haven’t. Robert Mugabe, President of Zimbabwe for the past 37 years, frequently seeks eye-related treatment 8,240 kilometres away in Singapore. Jose Eduardo dos Santos who has just stepped down as Angola’s leader after 38 years, also travels to Spain for treatment.

In the recent past, some African leaders died abroad while seeking treatment. Zambia’s Levy Mwanawasa died in France while the country’s Michael Sata passed away in the UK. Then there was Guinea Bissau’s Malam Bacai Sanha who died in France, Ethiopia’s Meles Zenawi who died in Belgium, and Gabon’s Omar Bongo who died in Spain.

A few fortunate ones made it home, but died shortly afterwards. They include Nigeria’s Musa Yar’Adua who died in Abuja after returning from treatment in Saudi Arabia, and Ghana’s Atta Mills who died in Accra after returning from a brief medical spell in the US

The picture painted above is shameful. As long as Africa’s leaders keep going abroad for medical reasons, the ambition for better health infrastructure will remain an illusion.

Costs and risks

Countries pay a heavy cost for this behaviour. It’s estimated that in Uganda, the funds spent to treat top government officials abroad every year could build 10 hospitals.

Not only do the leaders travel with elaborate entourages, but they also travel in expensive chartered or presidential jets. For example, the cost of parking Buhari’s plane during his three month spell in London is estimated at £360,000. That’s equivalent to about 0.07% of Nigeria’s N304 billion budget allocation for health this year. And there would have been many other heavier costs incurred during his stay.

The failure of leaders to improve health care and stem brain drain also carries a heavy price. A 2011 report estimated that nine African countries – including Nigeria and Kenya – had lost USD$2.17 billion of their investment in health care professionals. This figure might be higher now.

On top of this, African hospitals that were previously world class have been reduced to symbolic edifices due to political negligence. For example, Lagos University Teaching Hospital was once deemed to be one of the best on the continent. Recently, it was criticised for decadence. Not far away, Ghana’s flagship national health insurance scheme is ailing.

Essentially, when people charged with responsibility feel they have no need for public health systems because they can afford private health care at home or abroad, ordinary citizens bear the brunt.

The way forward

The effective health systems in western and Asian countries that are being patronised by African leaders only exist because they were developed, and are consistently maintained, through political commitment and visionary leadership, qualities that are clearly lacking in Africa.

To bring change, African citizens must start condemning political medical tourism. They must also push for regulations to curb the shameful practice. Taxpayer funded medical trips should be banned and criteria set detailing what sicknesses that can be covered by the public purse. Though a law to this effect exists in Nigeria, it appears to be ineffective. It must, and should work.

![]() Essentially, if the leaders do not experience the poor state of health care, they might never strive for any positive changes to it.

Essentially, if the leaders do not experience the poor state of health care, they might never strive for any positive changes to it.

Tahiru Azaaviele Liedong, Assistant Professor of Strategy, University of Bath

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.