South Africa Needs Better Food Price Controls to Shield Poor People from COVID-19 Fallout

COVID-19 has wrought havoc on poor households in countries across the world. In South Africa, more and more people are facing hunger resulting from mass job losses and small, poorly implemented supplementary cash grants. On top of this the pandemic has put in stark relief the country’s poorly understood food system, in which powerful firms […]

COVID-19 has wrought havoc on poor households in countries across the world. In South Africa, more and more people are facing hunger resulting from mass job losses and small, poorly implemented supplementary cash grants.

On top of this the pandemic has put in stark relief the country’s poorly understood food system, in which powerful firms operate with little oversight while vulnerable actors in the informal food sector face over-regulation.

When the country went into lockdown on 26 March 2020, government placed the formal food sector at the centre of continued food supply. Informal food vendors were restricted. Yet these vendors provide an important source of food and livelihoods for the majority of South Africa’s population.

The South African constitution recognises the right to food. But the government’s failure to enact specific legislation on food rights has resulted in incoherent food security policies. Even the smallest increases in prices of products in the basic food basket can have a significant impact on poor households and in local markets. Therefore, access to affordable and nutritious food through formal and informal food markets is critical for ensuring people’s right to food.

In this article, we highlight indicators of a distressing rise in the prices of essential food products that is contributing to South Africa’s hunger crisis. We call for the urgent expansion of price controls to items in the basic household food basket, as well as an inquiry into the price-setting of major retailers.

Have food prices increased?

StatsSA recently published the headline urban consumer price index (CPI) as having decreased by 0.5% month-on-month in April 2020. But the statistics body explicitly cautioned that its new price collection strategy had been severely limited by the lockdown regulations. The headline number potentially reflects very different pricing behaviour of major retailers that have an online presence. Moreover, smaller retailers are excluded from this methodology – despite comprising half of poor household food spending based on data from the Income and Expenditure Survey of 2011.

Evidence of large price increases on essential food items is recorded by the NGO Pietermaritzburg Economic Justice and Dignity’s price surveys. They find an 8.2% increase in the price of a household food basket for the three-month period from 2 March to 3 June 2020. This includes large increases in the prices of essential food items at the local level over the period, such as an 18% increase for sugar beans and a 14% increase for brown bread.

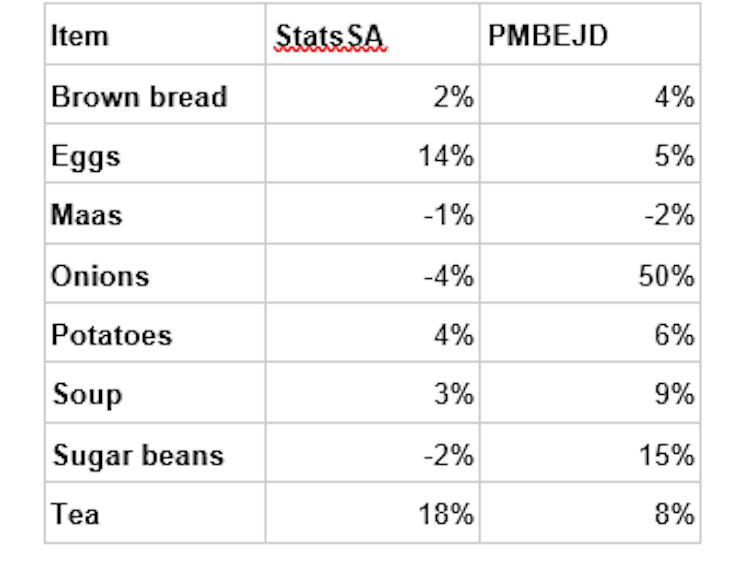

Table 1: Month-on-month price increases for essential food items, March to April 2020

Comparisons of the StatsSA and Pietermaritzburg surveys are limited by timing and availability of item-specific data. But both sources show that prices of brown bread, eggs, potatoes, salt, and soup increased in March and April. These are essential food items not necessarily monitored under current COVID-19 regulations.

Why is this not a Competition Commission case?

The price hikes have drawn the attention of the country’s Competition Commission. In a recent food price monitoring report it pointed out significant inflation in the prices of various food items. It commented that, in some cases, the increases and high margins were not justified by the changes in the operating costs of the suppliers.

Regulations introduced in March after the government declared a state of disaster to manage the COVID-19 pandemic empowered competition agencies to investigate firms believed to be charging excessive prices for certain essential healthcare and food items. But not a lot has happened. Although 38% of the 320 complaints received by the competition commission by the end of June related to food prices, only one has so far led to an administrative penalty for a firm. This was the Food Lover’s Market case relating to the price of raw ginger.

Cases of excessive pricing of goods and services are among the most difficult to prosecute. This is because of the complexities of determining the extent to which prices are high; relevant cost parameters that have to be considered; the reliability of benchmarks; and the availability of data.

What can be done?

During the most severe part of the lockdown in the country, the government addressed the issue of higher food prices by concluding an agreement with major retailers to limit price increases on key items. But this lapsed immediately after the first easing of the lockdown on 4 May. Since then retailers have increased prices of certain food items in response to higher input prices. We believe a renewed list of price limits should be put in place.

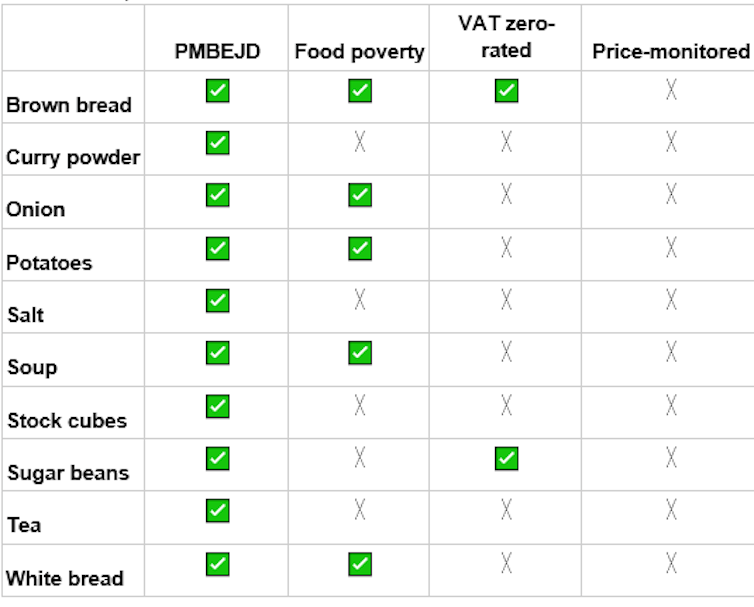

Along with capping price increases for key food items, we propose that the list of items subject to the price monitoring regime be broadened. The Competition Commission’s assessment – and our own – indicate that there has been some positive effect of the food price increase restrictions for food items already included in this list, such as maize meal and frozen chicken. But the published list of 22 critical products and categories, including 11 basic food items that are price-monitored, does not go far enough. The list of 11 food items leaves out brown bread and dried foods such as legumes, for example, which are staple foods for the poor and a major source of nutrition. The inclusion of frozen vegetables, on the other hand, points to poor targeting and a limited understanding of what constitutes the food basket of low-income households. Frozen vegetables are staples among middle-income households.

Table 2: Comparison of essential food baskets

We recommend the urgent expansion of the list to include brown bread, fresh vegetables, eggs and sugar beans, among other products. A failure to do this may well reverse any positive impact of increasing the rand values of social grants. At its core, the right to food is about protecting people’s right to feed themselves.

While the expansion of social protection measures does in part contribute to access to food for poor and vulnerable households, government should play a role in monitoring and regulating the food sector to ensure a more equitable and sustainable food system for consumers and actors in informal food markets. Price limits should be complemented by an inquiry into the price-setting of major retailers. The weaknesses in the StatsSA pricing data highlighted above indicate the need for more comprehensive data to inform ongoing monitoring of food prices.

The effects of COVID-19 will endure for some time to come, including large-scale job losses, and so it is certainly not too late to intervene. Poorer South African households cannot continue to endure both a crisis of joblessness and food price increases.![]()

Ihsaan Bassier, Phd candidate in Economics, University of Massachusetts Amherst; Refiloe Joala, Researcher and PhD candidate at PLAAS, University of the Western Cape, and Thando Vilakazi, Executive Director of the Centre for Competition, Regulation and Economic Development, University of Johannesburg

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.