Four things that count when a South African graduate looks for work

For many young South Africans, a qualification is perceived to be the passport to a good job and decent salary, opening the way to a better life for them and their families. South Africa’s private higher education sector has grown rapidly since 1994, when the education system began to expand under democracy. The number and […]

For many young South Africans, a qualification is perceived to be the passport to a good job and decent salary, opening the way to a better life for them and their families.

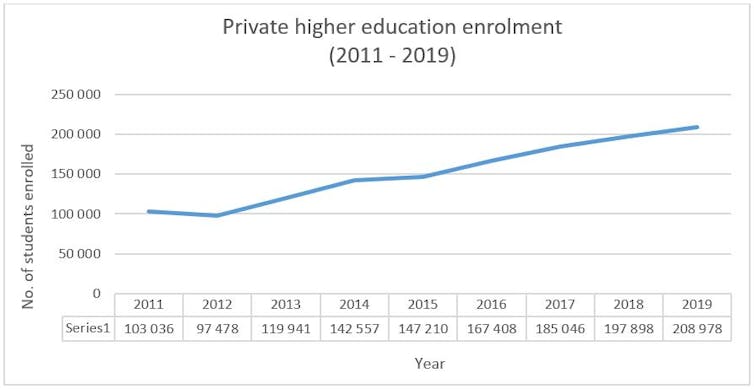

South Africa’s private higher education sector has grown rapidly since 1994, when the education system began to expand under democracy. The number and types of private institutions have increased and student enrolment more than doubled between 2011 and 2019.

There are currently 130 registered private higher education providers. These institutions enrol about 210,000 students, and produced more than 42,000 graduates in 2019.

The sector is diverse in terms of institutional reputation, size, ownership, fee structure and student demographic.

In South Africa, the term “university” is reserved for public higher education institutions according to the Higher Education Act. Consequently, private higher education may be perceived as not on par with university education. But there’s little difference between the sectors as far as qualification standards are concerned. All private institutions must be registered with the Department of Higher Education and Training, and need to comply with the same programme accreditation and quality assurance requirements as public universities.

One advantage that private institutions may have – because they are smaller – is the flexibility to adapt their offering relatively quickly to meet the needs of the market. Many deliver niche vocational programmes, using industry experts as educators, with the specific intention of producing more employable graduates.

But do they? Between 2018 and 2020 I conducted research into whether this goal was being achieved. I evaluated the opportunities provided by private higher education institutions in South Africa and the employability of their media graduates, specifically.

I found that the percentage of graduates who found employment was relatively high. But the employment outcomes varied among graduates, strongly shaped by personal biographies as well as enrolment choices and options, and mediated by the type of institution.

These findings may be of use to higher education managers, educators, researchers and policymakers. Attention needs to be given not only to the knowledge and skills graduates require for employment but also the other factors that give graduates a better chance of earning a decent livelihood and participating in society.

Employability of graduates

The research focused on graduates who studied to work in journalism, public relations, graphic design, and creative and visual communication, including radio and television production and broadcasting. These fields are rapidly changing and increasingly digitalised. Participants came from three private institutions – elite and non-elite – and had been in the workplace for between one and five years.

I found that four things counted for employability: the reputation of the institution; networks and connections; experience; and type of work.

Qualification doesn’t equate to a job. Within five years of graduating, 84% of the graduates were working. Yet some – mostly from disadvantaged backgrounds – remained unemployed. And it seemed their opportunities were diminishing.

Having a job doesn’t equate to earning a decent livelihood. Many graduates were underemployed. Some had taken jobs in factories, retail or administration, merely to earn some income.

One-third of the employed graduates earned less than R10,000 ($700) a month, and 11% of those earned below R5,000 a month. That isn’t far off the minimum wage. There was a pattern: most of the low-wage earners were black graduates from non-elite institutions.

Experience is essential. Employers recruit from their industry network. Eighty per cent of the study participants had participated in some form of internship to build a base of working experience. But the monthly stipend ranged from R2,000 to R4,000 (between $130 and $270), which barely covered transport costs. This means that graduates who can be financially supported by family take on internships. Those from poor families are less likely to be able to afford the benefit of these employment-enhancing opportunities and go in search of any job. Hence their disadvantage persists.

An institution’s reputation counts. Employers partner with higher education institutions. They contribute industry-relevant input to the curriculum and teaching and then recruit directly from the institution’s pool of graduates. Employers admitted that they favour graduates from particular institutions while those from other institutions are overlooked.

Equipped for the real world

Deeper analysis of graduates’ employment status showed patterns of employment were divided along lines of race, socio-economic status, educational background and institution. These findings are similar to those of studies on the employability of graduates from public universities. They call into question the value of investing in private higher education, and whether private institutions provide equitable opportunities for all graduates.

The findings confirm that skills, knowledge and qualification don’t ensure successful employment outcomes for graduates. Higher education cannot overcome structural constraints such as a saturated labour market, a weak economy and entrenched social inequality. More of the same from institutions, irrespective of the quality of the education, will likely continue to reproduce unequal outcomes.

The need for private institutions in South Africa to take note of this reality is even more important in the context of COVID-19 and the recent social unrest, and the implications of these macro issues on graduates’ livelihoods and lives.

Policies should recognise that some individuals require different strategies, resources and ways of teaching to achieve the same outcomes as others. Students need to be guided and supported in their choices from the outset, learning how to build networks, gaining real work experience, and preparing for various types of work in a range of contexts.

Graduate preparation must move beyond employers and employment. Institutions ought to focus on enhancing graduates’ abilities to navigate their way in society, to respond to opportunities to work and earn, and to be adaptable so they can thrive in an uncertain world.![]()

Fenella Somerville, Post-doctoral research fellow in the SARCHI Chair Higher Education and Human Development research group, University of the Free State

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.