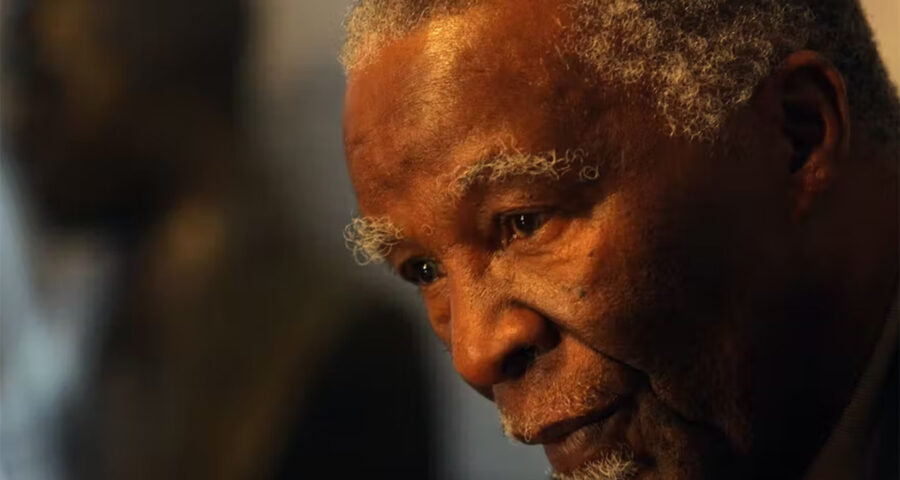

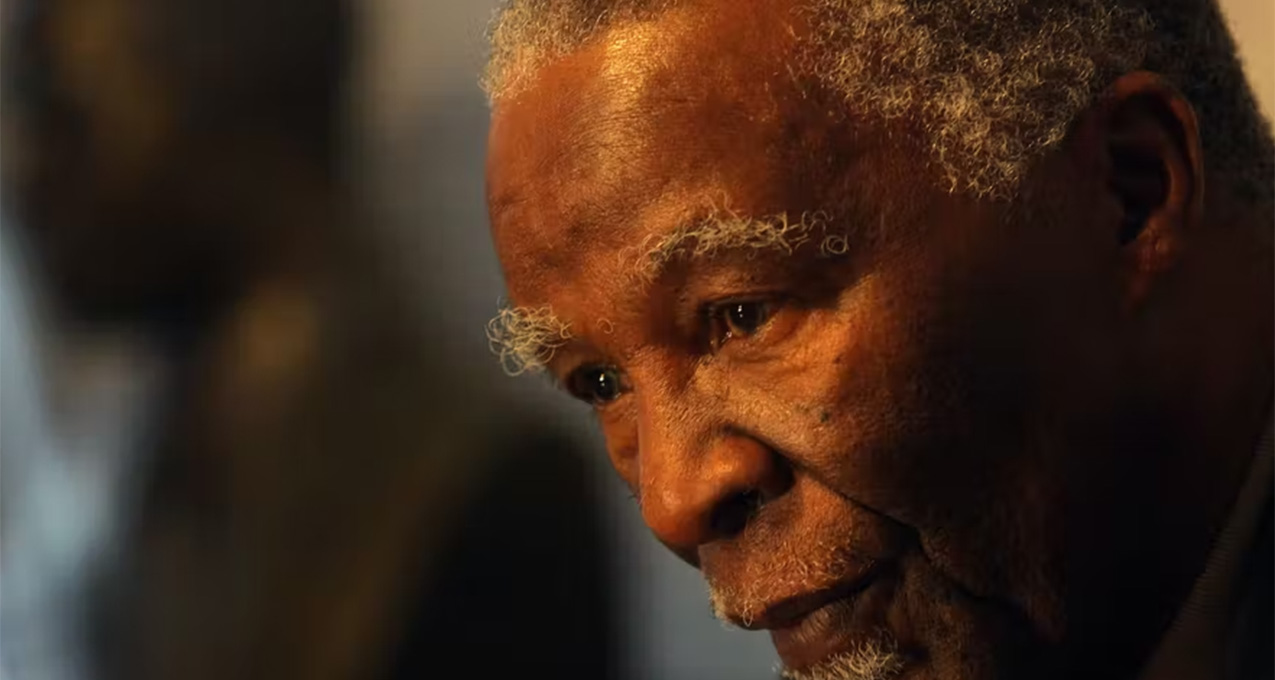

South Africa’s Thabo Mbeki at 80: Admired on the Continent More Than at Home

Thabo Mbeki, who succeeded Nelson Mandela as South Africa’s second post-apartheid president, celebrated his 80th birthday on 18 June 2022. Following Mandela’s era of multiracial and multicultural rainbowism, Mbeki had to squarely address the challenges of acute inequality and the numerous grievances of the black majority caused by colonialism and apartheid. This was tough work […]

Thabo Mbeki, who succeeded Nelson Mandela as South Africa’s second post-apartheid president, celebrated his 80th birthday on 18 June 2022. Following Mandela’s era of multiracial and multicultural rainbowism, Mbeki had to squarely address the challenges of acute inequality and the numerous grievances of the black majority caused by colonialism and apartheid. This was tough work with no easy solutions.

Mbeki was born in what is now the Eastern Cape province to fairly educated and politically conscious parents – Epainette, a schoolteacher, and Govan, a contemporary of Mandela and other freedom fighters of that era. Govan was seldom home as he pursued the cause of freedom for South Africa. Thabo had to grow up fast and joined the youth league of the African National Congress (ANC) when he was only 13.

The topic of Mbeki’s political legacy is moot. Even his position between global icon Nelson Mandela and alleged state capture architect Jacob Zuma is quite telling. For the most part, Mandela, whom he succeeded, basked in the glow of post-apartheid reconciliation and euphoria. But Mbeki could not afford that luxury. There was serious work to be done in building a post-apartheid political dispensation. Much of this arduous task fell on him, whom many considered Mandela’s de facto prime minister.

Mbeki is attractive to many intellectuals beyond South Africa because of his thinking about pan-Africanism, the African renaissance and neocolonialism. All these issues are pertinent in Africa and its vast diaspora, which put Mbeki in the spotlight of the pan-Africanist movement. Numerous works have been written on his tenure as president and his legacy. (WATCH Thabo Mbeki’s I am an African Poem)

Mbeki found his second wind as probably the most respected African elder statesman after his ignominious exit as ANC leader. His transition from national politics to the African continental stage has been without great fanfare but quite effective.

As the ANC, which has governed South Africa since 1994, became afflicted by widespread corruption and deadly politicking, Mbeki kept above the fray. His nemesis and erstwhile deputy, Zuma, who succeeded him as president, went further in tarnishing the ANC brand and legacy in the most disrespectful manner.

This is the uncomfortable position from which Mbeki is compelled to be assessed.

A no-frills technocrat

Mbeki is not a charismatic leader, neither does he pretend to be. He does not possess Mandela’s charm or Zuma’s demotic earthiness, which can move people to declare they’d kill for him.

Mandela had a winning smile that floored Hollywood A-listers. Zuma sang and danced his way into the hearts of the South African masses and wasn’t afraid to make a fool of himself. Mbeki always remained aloof. His appeal was largely among intellectuals.

Mbeki is rather a conscientious technocrat equally at home with other technocrats such as Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka and Trevor Manuel. The two served in prominent positions in Mbeki’s cabinet.

During his tenure as ANC president (1997-2007), Mbeki couldn’t woo the rank and file in his party with rousing speeches delivered with visceral directness. That isn’t his forte. He is, instead, a manager of systems and institutions and a purveyor of ideas.

Downfall and resurrection

Mbeki is a promoter of pan-Africanism – the quest to unite Africans in pursuit of a united, prosperous Africa. Frantz Fanon, the Haitian revolution, the Harlem Renaissance and important milestones of black empowerment powerfully shaped Mbeki’s ideological make-up. There is a certain cosmopolitanism present in his outlook. But the masses of the South African people did not appreciate it. Instead, he was deemed cold, unresponsive and, therefore, uninteresting. This, more than any other failing, was the reason for his political downfall.

His detractors and the party cast their lot with a more engaging Zuma in December 2007, which turned out not to be the best of choices. Mbeki was subsequently unceremoniously fired as president of the country by the ANC in September 2008.

Mbeki’s rejection by his party undoubtedly reduced his political influence within the ANC. But he did not become idle. He worked diligently on the continental African stage, where his expertise and experience are highly valued. He has been traversing the continent on behalf of the African Union, putting out political fires and helping broker peace with an energy and commitment that many of his age don’t possess.

While Zuma reigned supreme in the ANC from 2007 to 2017, Mbeki kept a respectful distance. All through Zuma’s scandals and motions of impeachment, Mbeki more or less maintained his silence and dignity.

Zuma, on the other hand, abdicated his powers to a shady cabal that influenced key government appointments and commandeered most of the lucrative government contracts of the ANC-led administration.

Then people started to think that perhaps Mbeki wasn’t that bad after all. Some might argue that he had dictatorial tendencies but he was always his own man. Under Zuma, foreign actors without the least connection to the South African electorate wielded unimaginable power and influence.

After years in a political purgatory, Mbeki seems to have undergone a resurrection, based on the unmitigated disasters of his successor. He is now helping to save the ANC.

Africa’s elder statesman

It is a pity that Mbeki’s invaluable work on continental affairs isn’t much valued in South Africa.

Beyond South Africa, Mbeki is increasingly being considered among African intellectuals such as Toyin Falola (Nigeria), Paul Zeleza (Malawi) and Mammo Muchie (Ethiopia). He’s placed in the same league as African philosopher-kings like Senegal’s Leopold Sedar Senghor, Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah and Tanzania’s Julius Nyerere.

At 80, Mbeki still articulates his pet concerns of African unity, African renaissance and pan-Africanism with diligence and precision. His analyses are usually well-considered and deserving of attention. His interventions to end the Ivorian and South Sudanese crises are noteworthy.

Mbeki continues to function as probably the most resourceful elder statesman on the African continent. For instance, he is involved in efforts to solve the impasse that has pitted Anglophone Cameroonians against their Francophone counterparts.

He is also involved in efforts to resolve the crisis in the Great Lakes Region. The conflict has been called Africa’s first world war because of the number of external actors and African nations engaged in the scramble for the region’s mineral wealth.

Because violence anywhere on the continent tends to have broader continental consequences, Mbeki makes it his business to try to prevent outbreaks of war and mayhem.

In Cote d’Ivoire, he led initiatives to resolve the confrontation between two presidential aspirants, Alassane Quattara and Laurent Gbagbo. Their bloody stand-off put their country into a downward spiral. Finally, Mbeki has advised that to end the civil war in South Sudan, all the stakeholders must be involved in the peacemaking process.

It is clear that Mbeki has successfully transitioned from being an old horse of his party, the ANC, to a highly venerated and in-demand African elder statesman. And just as Nkrumah was, he is more respected on the continent than in his country. Given his attitude, composure and utterances, Mbeki seems quite natural in speaking and acting on behalf of the entire continent.![]()

Sanya Osha, Senior Research Fellow, Institute for Humanities in Africa, University of Cape Town

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.