Tanzania at 56: Echoes of the Best and Worst of Nyerere Under Magufuli

The Tanzanian mainland is marking the 56th anniversary of independence from British rule. The mainland unified with Zanzibar in 1964 to create the current nation-state under Mwalimu Julius Nyerere who is often invoked as “the father of the nation”. The new nation-state’s economic, social and political path was paved in 1967, when Nyerere proclaimed the […]

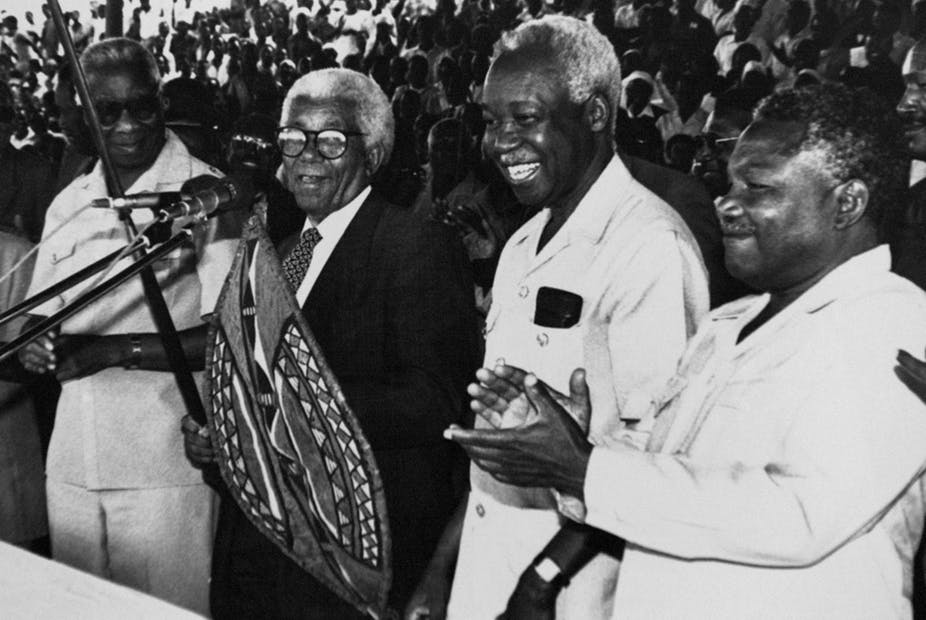

The Tanzanian mainland is marking the 56th anniversary of independence from British rule. The mainland unified with Zanzibar in 1964 to create the current nation-state under Mwalimu Julius Nyerere who is often invoked as “the father of the nation”.

The new nation-state’s economic, social and political path was paved in 1967, when Nyerere proclaimed the Arusha Declaration. This led to the nationalisation of key industries and the total reorganisation of rural life. Communal farming and forced resettlement were applied, justified on the basis of attempting to bring about self-reliance.

Referred to as ujamaa, the socialist-inspired policies dominated the politics, society, and economy of Tanzania until Nyerere’s retirement in 1985.

Ujamaa policies are much debated. Generally, they are seen as something of a social success but as economically ruinous. By emphasising Tanzanian citizenship, ujamaa created a sense of unity and effectively removed the kind of ethnic politics that dominates Kenya, for example. But it short-circuited the economy and saw food production collapse.

Nyerere’s handpicked successor Ali Hassan Mwinyi Tanzania practically reversed all the earlier policies. His government moved from one of the most influential and vehement defenders of African Socialism to one of the most neoliberal regimes on the continent. As Pitcher and Askew thoughtfully assert, this really put the “self” in “self-reliance”.

This openness to investment and trade was further enhanced with the introduction of multipartyism in 1995. Under both Presidents Mkapa and Kikwete, the country generally remained economically liberal. It also remained investment friendly with significant levels of foreign investment when compared to the socialist period.

But sweeping change has come under the current President John Pombe Magufuli, who has just entered the third year of a five-year term. Magufuli has taken a different approach to that of his recent predecessors and is harking back to policies advocated by Nyerere. Comparisons between the two are commonplace, both positive and negative. This is particularly so when it comes to natural resources.

Perhaps the most contentious area today is the mining sector and the role of the contemporary government in seeking better returns from mining companies. This move has the hallmarks of a policy of resource nationalism. This is a sign of a shift in policy as well as rhetoric.

Opening a closed economy

Tanzania was close to bankrupt after the economic collapse of the 1970s and the conflict with Idi Amin’s Uganda in the late-1970s. The latter years of Nyerere’s presidency were marked by his continual attempts to resist IMF assistance which involved signing up to a structural adjustment package. This was mainly down to his concerns over dramatic cuts to social provision.

The first programme was finally implemented in 1986 under Mwinyi whose presidency was marked by Tanzania’s economy opening up and dramatic reductions in social expenditure.

Multi partyism also arrived in Tanzania. The first multiparty elections in 1995 were won by Benjamin Mkapa who remained in power for the next 10 years. Another 10 years followed under Jakaya Kikwete until 2015.

During this period foreign investment has come in many sectors, but especially in tourism and mining. A significant part of the financial inflows came from post-apartheid South Africa.

“The Bulldozer” approach

“The Bulldozer” Magufuli is Tanzania’s fifth president, and the fourth since multiparty elections. As he enters his third year,

there are strains of authoritarianism in Magufuli’s approach which bear the hallmarks of Nyerere. For example, he seems to have centralised power within the executive branch of government.

At the same time, he seems to be placing himself more closely to the socialist era of Tanzanian politics than anything since Nyerere.

Both approaches seem politically acceptable to Tanzanians – as long as they generate results. Nevertheless, Magufuli’s approval ratings fell to 71% in June from a high of 96% last year.

It’s still unclear what effect his recent attempts to claw back revenues from multinational mining giants will have on his rating.

New regime for mining

In the Arusha Declaration, Nyerere describes natural resources as owned by all citizens and held in trust for their descendants. When the new mining laws were passed in July, Magufuli said:

We [Tanzanians] must benefit from our God given minerals and that is why we must safeguard our natural resource wealth to ensure we do not end up with empty mining pits.

The new laws raise royalties on tax for gold, copper, silver and platinum exports from 4% to 6%. This is a nominal increase perhaps but an indication of a different direction of travel. Expectations are that such changes will soon be introduced for tanzanite and diamonds.

Following the new laws the government agreed a 50-50 profit sharing arrangement with Barrack Gold as well as a minimum government of stake 16% in all mining activities. Gold generates around a third of the country’s export revenues.

The new mining laws aren’t akin to the nationalisation of 50 years ago. But Magufuli has described the agreement with foreign investors as groundbreaking and a model to be adopted elsewhere across the continent.

The long term impact of mining reforms are yet to be felt. Claims from multinational corporations that the new laws threaten future investment may well prove to be overblown. As might the opinion pieces in The Economist suggesting Armageddon for the sector in Tanzania. But, certainly from some quarters, the view is that Magufuli has managed the process well.

On the other hand, his bulldozing style has seen his popularity decrease. It has also seen critics express their views over his presidency more forcefully.

A balance sheet of positives and negatives is perhaps the most striking similarity with the legacy of Nyerere as Tanzania marks yet another independence anniversary.

![]() I would like to thank Alessio De Vito for her blog as part of our African Politics course at the University of East London. It certainly informed my ideas for this article.

I would like to thank Alessio De Vito for her blog as part of our African Politics course at the University of East London. It certainly informed my ideas for this article.

***

Rob Ahearne, Senior Lecturer in International Development, University of East London

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.