Amen: Football’s forgotten heroes

by Nicky Rehbock With the spotlight firmly fixed on South Africa during the 2010 Fifa World Cup, it’s easy to forget what the game of football is like elsewhere on the continent – played far, far away from glitzy stadiums, often in remote dusty villages with hand-made balls, bare feet and a couple of crooked […]

by Nicky Rehbock

With the spotlight firmly fixed on South Africa during the 2010 Fifa World Cup, it’s easy to forget what the game of football is like elsewhere on the continent – played far, far away from glitzy stadiums, often in remote dusty villages with hand-made balls, bare feet and a couple of crooked sticks for goal posts.

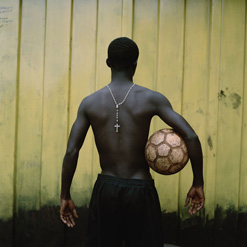

This is what photographer Jessica Hilltout is trying to show. Her recently launched book, Amen, seeks to draw attention to the spirit of grassroots football in Africa, and the highly dedicated players and teams that follow the game as if it were a religion.

“All the people who live and will remain in the shadow of the World Cup deserve to have a light shone on them, not just for their passion for the game, but more so for the fundamental energy and enthusiasm that shines through the way they live,” she says.

In this regard her work delves deeper than the sport itself: “This book is not just about football, or indeed about football in Africa. It is a book that tries to capture the beauty and strength of the human spirit. It pays homage to Africa. It is a tribute to the forgotten, to the majority,” Ogilvy & Mather’s creative director Ian Brower writes in the introduction.

“Africa is a world like no other … there lies a passion for the festival, a reason to rejoice. These moments are centred around music and football. Often the two go hand in hand. Football is the one activity that costs nothing.”

So be it

Hilltout believes, and has largely based her work on the premise, that in Africa, football is not a religion, but everything a religion should be. “Football is the glue in Africa – it’s a necessity,” she says.

“In every little village, no matter how far off the main road, I’d find people playing football at sunrise and sunset. One small village could have as many as five football fields. Waking up at dawn I’d join the players and spectators gathering together on the football field, like we were congregating at a shrine or a temple. There was a true sense of devotion to the game.”

The book’s title is also based on this sentiment. “Amen is a four-letter word, the same in every language. It means ‘so be it’,” Hilltout says.

“This is very pertinent to Africa in terms of how people accept their fate, with pride and dignity, tough as it may be. It was also the word I heard the most during my trip. When I would leave groups I had been working with, they would say to me: ‘Amen, amen. May this project work. Amen, amen.’ ”

A life on the road

Hilltout, who was born in Belgium in 1977, is no stranger to travelling and a life on the road. As a child her family moved around a lot and spent time in the Seychelles, US, Canada, Hong Kong and South Africa.

After studying photography in Blackpool, UK, and a brief stint in advertising in Europe, she bought an old Toyota Land Cruiser with her boyfriend in 2002 and made a 15-month trip from Belgium to Mongolia.

Following this, the two shipped the car to South Africa’s port of Durban and drove up through Africa, back to Brussels. Throughout the journey, Hilltout kept log books and a photographic record of the regions and places she explored.

“Although there was no thread holding my work together at that stage, it was the foundation of what I am trying to express now: highlighting the value of simple, banal things – that stuff that people usually overlook. My first photographic project that held any ground was called the Beauty of Imperfection, which Amen is linked to. It also pays tribute to the imperfect.”

Return to Africa

It was Christmas 2008, back in Europe, when the upcoming 2010 Fifa World Cup sparked the idea of a grassroots football book for Hilltout and her dad, who ended up working with her on the project. “We thought, that with this huge event happening for Africa as a continent, why don’t we show everyone what football means in the little villages, cities and towns across Africa, the places that aren’t going to be the focus tournament?”

For the project, Hilltout concentrated on Southern and West Africa, covering about 20 000km between South Africa, Lesotho, Mozambique, Malawi, Ghana, Togo, Benin, Burkina Faso, Niger and Côte d’Ivoire.

“There was no real planning for the trip. Nothing had really been pre-arranged. I got on a flight to Cape Town from Brussels, and with me was a Hasselblad with one 80mm lens, 300 rolls of film, a digital camera, my log books, a mini printer and a stock of new footballs. I packed this all into an old VW Beetle that was equipped with a roof rack, three spare tyres, two jerry cans and a higher suspension.”

Southern Africa was a natural choice because Hilltout’s dad had the Beetle stored in Cape Town, so she borrowed it for that portion of the trip, but West Africa was a more spontaneous choice.

“I decided to go to West Africa because I had never covered that region before … and I knew there were lots of big football countries there, like Ghana and Ivory Coast – so I just flew to Accra. Once I arrived there I bought a Nissan Vanette and kitted it out with four big boxes: one for footballs, one for food and the other two for clothes and film. The whole trip was done on gut-feeling. I would literally arrive in a village … start talking to people … show them my log books with the ideas I had for the project … then off we’d go.

“All in all I spent seven months on the road and worked in about 20 different places across the two regions. Each place has a story to it, and that’s covered in the book. There are stories about the guys who fixed boots in the villages, the guy who took in hard-up youngsters and mentored them, and the guy who owns a ‘football cinema’ in West Africa that’s built of mud and sticks, but it can seat 60 fans – and you can even get a fried egg and cup of coffee in there while watching the game!

“After this I returned to Europe to put it all together. In total I spent about two years on the project.”

Communicating with locals wasn’t too much of a problem for Hilltout, as she speaks English, French and Spanish, but she admits things were a little difficult in Mozambique, as she couldn’t converse in Portuguese. “I drafted a letter and got it translated from Spanish into Portuguese and addressed to the chiefs of the villages I intended visiting.”

The contacts she made in the bigger towns, who she says became “her very good friends”, helped her connect with communities in far-off places and translated when only an African language was spoken.

“The people with whom I worked were all essential to this project. Once they understood the message I was trying to portray, once I’d gained their trust, they gave me more than I could ever have dreamed. They let me into their villages and homes. They proudly showed me their shoes, their balls, their jerseys.”

Trust was a big thing, Hilltout says. “Sometimes it took three days before I took out my camera. I was very aware of the fear of deception, and how these people had perhaps been promised things before. They think people are coming to take – not to give back. And I think this is very well reflected in the history of Africa.”

Tired balls

Throughout her trip she exchanged the manufactured footballs she’d brought along for more intricate, home-made ones put together with old socks, pieces of cloth, string, plastic bags and – believe it or not – condoms. Hilltout says that once inflated and covered in a few protective layers, these can keep a ball bouncy for up to three days!

“Eventually I found myself with 35 such balls and realised the extent to which they represented the essence of my trip and the heart of the project. I am looking to exchange the balls I collected for equipment for all the players who made this project come to life… so that they can keep on playing the game they love,” she says.

UK sports writer and author David Goldblatt talks about this collection extensively in the foreword to Amen: “A few years ago I wrote on the opening page of The Ball is Round: A Global History of Football: ‘Football is available to anyone who can make a rag ball and find another pair of feet to pass to’, as if making a rag ball were a simple matter.

“How glib, how foolish, and from a man who had never made a rag ball in his life. I still have not made a rag ball, but I have had the good fortune to see the photographs in this book, Jessica Hilltout’s Amen, and I will never take the manufacture of footballs, from any material, so lightly again.

“Amongst the many things that I have learnt from this book, is that getting or making that ball is no simple task. On the contrary, it is emblematic of the inventiveness, diligence, creativity and single-minded focus of Africans in particular, but of poor communities everywhere,” Goldblatt writes.

Exhibitions and book sales

The photographs in Amen are currently on exhibition in Johannesburg, at Resolution Gallery, and will also be shown in Cape Town, at the Joao Ferreira Gallery, from 15 June to 24 July. A similar exhibition will take place in Brussels, Belgium, from 10 June until 18 July.

The 208-page hardcover version of Amen is currently available in all major South African book stores for R600 (US$77), and available in magazine format for R190 ($24).

Where to from here?

“Part one of my campaign is to get the word out about the book, and then the next step is to use the publicity and funds generated from it to make a sustainable contribution to the football communities I photographed in Africa,” Hilltout says. “Of course, I can’t go back and help everyone, but want to focus on two highly committed groups I met in West Africa.”

While Hilltout is working to make a positive change in lives of those she photographed, she says her own outlook has changed too.

“The life lessons I learned in Africa could never have been learned in Europe. This project has changed me. I’ve begun to understand the true importance of football, which would have been impossible if I hadn’t lived through all the stories in order to capture the pictures. Through football I think I understand a little more about life, or at least a certain way of living.”