Social housing in South Africa is in trouble – here’s why

South Africa’s nascent social housing sector is facing systemic struggles. Rising construction costs, slow release of land, and insufficient grant funding are compromising the sector’s ability to deliver new units at the pace and scale needed. Social housing is the key to moving beyond apartheid urban planning, but it is faced with myriad challenges. GroundUp […]

South Africa’s nascent social housing sector is facing systemic struggles. Rising construction costs, slow release of land, and insufficient grant funding are compromising the sector’s ability to deliver new units at the pace and scale needed.

- Social housing is the key to moving beyond apartheid urban planning, but it is faced with myriad challenges.

- GroundUp spoke to social housing experts to learn why progress on building new social housing units is slow.

- Rising costs, small and insufficient grant funding, and slow land release are key reasons why social housing institutions are struggling.

- Experts say that the future of social housing depends on local governments in particular making life easier.

South Africa has a critical shortage of decent, affordable housing, and its cities continue to reflect apartheid planning. Social housing is the only of South Africa’s housing programmes that directly and explicitly targets spatial transformation.

A recent report from housing advocacy group Ndifuna Ukwazi highlights the stark mismatch between Cape Town’s formal housing market as it stands and the housing needs of the population. “While 76% of Cape Town’s population earn below R22,000 per month, only 34% of all formal homes cater to households in this income range”.

GroundUp spoke to four leading figures involved in the social housing sector and housing activism to find out what is keeping us from building many more affordable housing rental units in our cities.

The fine margins

Social housing aims to provide good quality, well-located and affordable rental accommodation to low-income and ‘gap market’ households. ‘Gap market’ households are those that earn too much to qualify for other types of housing assistance, like RDP houses, but who earn too little to afford the commercial housing market. These are households with gross monthly incomes between R1,850 and R22,000.

Most social housing projects are developed, owned and managed by non-profit Social Housing Institutions (SHIs). SHIs are accredited by, and fall under the oversight, of the Social Housing Regulatory Authority. The law also allows for-profit private actors called Other Development Agents (ODAs) to participate, as long as they make a 20% equity investment in the social housing project. In such cases, the social housing project in question is subject to accreditation and compliance monitoring by the regulator, but the ODA itself does not require accreditation.

A completed social housing project will typically have different tenants paying different rates, according to their means. The SHIs don’t decide these rental rates on their own. They must follow the regulator’s guidelines for rent setting. For instance, the regulator’s latest policy revision sets an average base rental (i.e. excluding utilities and surcharges) target of R3,377 and an average rent quote (i.e rent as a share of gross household income) of 31.5%.

The rentals themselves are not directly subsidised. SHIs receive subsidies from the government to build new social housing projects; they do not receive regular subsidies to help cover the cost of operating existing ones.

These running costs must be covered by the rents collected, which also have to cover repayment of any loans taken out by the SHI to pay for its share of a particular housing project’s development costs (see this GroundUp article for a detailed example).

The subsidies typically cover 60-70% of a project’s capital costs, former National Association of Social Housing Organisations (NASHO) General Manager Malcolm McCarthy told GroundUp. This is what allows for significantly lower rentals than those charged in the private market.

The regulations also place limits on rental increases, and require projects to be developed in particular areas to receive the main subsidy for capital costs – so-called ‘restructuring zones‘ identified by local government.

Ideally, there will be a surplus between the revenue from rental income and the total costs associated with that project. The surplus would go toward funding the development’s long-term maintenance and or would be reinvested in a new social housing project.

But these ideal conditions are increasingly difficult to achieve for many SHIs.

Social is small

Social housing currently accounts for around 1% of housing delivery in the country, according to Anthea Houston who is the CEO of Communicare, an SHI, and the president of NASHO.

The latest available State of Social Housing Report (published by the regulator) indicates that 6,000 social housing units were delivered in Cape Town from 2005 to 2020 across 21 projects. Accounting for NASHO data on Communicare’s pre-2005 projects and more recent data for units delivered from 2019-2022, the total number of units in Cape Town can be estimated at between 10,000 and 12,000.

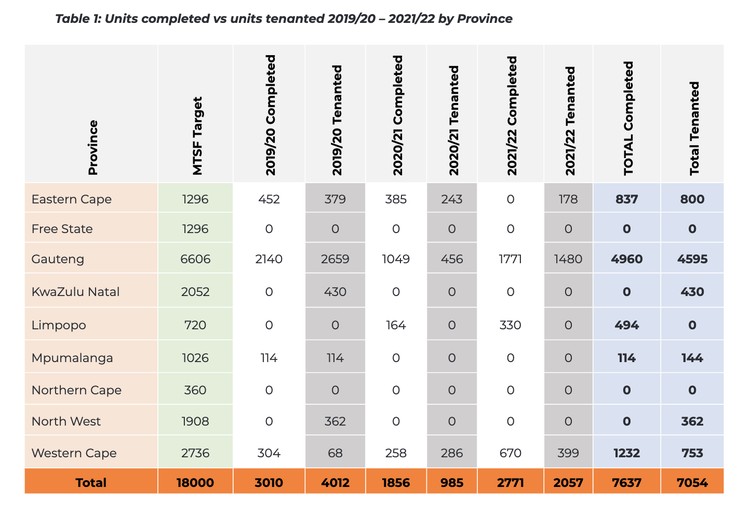

In recent years, progress on new construction has been patchy.

The above table from the regulator’s 2021/2022 annual report shows little to no sector growth in the Free State, the Northern Cape, the North West and KwaZulu Natal. Gauteng, the Western Cape, and the Eastern Cape are the largest contributors to new social housing stock, with smaller additions in Mpumalanga and Limpopo.

The sector’s growth seems to be sluggish and inconsistent.

Government grants aren’t adjusted quickly enough

Why aren’t we seeing more social housing developments? One reason is that the current grant funding model does not meet the needs of social housing providers, who want to build many more units and who face a difficult operating environment.

Houston explains that unlike those of other major housing programmes, the social housing grants are not automatically adjusted for inflation.

“The value of the grant is literally eroding with every passing year quite significantly,” she told GroundUp. “At least in recent years the minister has done adjustments every second or third year, but it requires advocacy every time. It would be easier if they just revise the way they are treating this grant to align with how they treat the other housing grants”.

Rising operating costs

But the day-to-day model of operating social housing is also fraught with problems.

The regulator’s most recent strategic planning document, published in March 2020, notes that rising operating costs are making it significantly harder to keep rentals affordable, particularly for the programme’s primary target tenants, those with monthly household incomes of R1,850 to R6,700. The report finds that tenants are also struggling to afford the current rates of rental. This undermines the regulator’s core mission, the document states.

“On the one hand we’re locked into a low return on the investment we make because that’s the intention with social housing,” says Houston; “But you need a mechanism on the other side to keep costs down because our economy is very inflationary.”

The major counterweight here is supposed to be scale – larger developments, and more of them.

Houston explains: “To actually cope with those runaway costs, you need to get to a scale in your operations. Then you can negotiate better service provider rates because of the volume you are able to give them from the number of buildings, the number of properties.”

Government grants aren’t big enough to meet SHI aspirations

Houston explains it is not just that grants must be adjusted in good time to account for inflation, but that larger grants are needed.

SHIs want to build at larger scales and in greater densities, but cannot afford to. This is largely because going from low- to medium-rise buildings comes with many additional up-front costs related to building safety regulations and other requirements.

“The minute you go above five stories, the cost of building increases phenomenally because you have to dig much deeper. You also have to install lifts,” said Houston.

Being able to cover the extra upfront costs both increases the financial viability of any given project and increases the number of households that can benefit from it.

This is particularly relevant in Cape Town where, in the areas best suited for social housing, private land is typically very expensive and there is only so much underutilised public land that the state can provide.

Land release holding social housing back

Houston says that the ability of SHIs to expand quickly enough to keep up with rising costs is being compromised by the slow pace of land release. The share of the national housing budget allocated to social housing is also shrinking year-on-year due to underspending. Houston says in the case of Cape Town, underspending in the current pipeline of projects is caused by delays in the land release process for the past decade.

Social housing’s mandate is to provide affordable housing to poorer households, “in support of spatial, economic and social restructuring” (according to the regulator). To achieve this goal of restructuring, social housing is built in restructuring zones, which are areas of major social and economic opportunity which are typically unaffordable to low-to-lower-income, largely black and coloured target households.

By contrast, housing programmes like Breaking New Ground (BNG, formerly RDP) housing and the Upgrading of Informal Settlements Programme (UISP) tend to be on a much larger scale since they are concentrated in outlying areas where development costs, particularly that of land are, cheaper. But by the same token, they don’t address the problem of apartheid spatial planning.

In recent years, this mandate to build social housing in well-located areas has fallen short of its ideal. A 2021 research paper by Dr Andreas Scheba, Dr Justin Visagie and Professor Ivan Turok highlights a significant ‘spatial drift’ of social housing in major cities. The trend in new social housing development is a shift from projects in the inner city and core suburbs where economic opportunity and public services are concentrated, toward more outlying areas where the process is easier and cheaper.

Housing activists have called on local governments to fast-track the release of well-located public land at a significant discount for affordable housing, including social housing. This is a role for local government, but can also depend on the provincial or national government, for example in the case of underutilised land on military installations.

The long-running dispute in and outside court between the Western Cape provincial government and housing activist group Ndifuna Ukwazi over the future of the Tafelberg site in Sea Point is a case in point. “If there’s no land coming from the state then social housing doesn’t really work because the cost of land in Cape Town is so high,” says Houston.

An apparent breakthrough in 2017 saw the City of Cape Town commit to a proactive role in sourcing land for social housing, It announced it had identified 13 pieces of well-located public land for future affordable housing development, all within five kilometres of the city centre.

But little progress followed.

“For about three years, although the pipeline was there and had done some initial pre-feasibility [studies] on that particular pipeline, the political pushback just caused huge problems,” recalled McCarthy. He notes that this was also caught up in the split between then-mayor Patricia de Lille and her allies in City government – who had championed this new approach – and DA party leadership; “It just mired the whole thing in all sorts of political contestation.”

A city takes up the challenge

McCarthy reckons that much of the political resistance to this land release process has since been overcome, with the team handling the issue of social housing within the municipality has made excellent progress on the procedural prep work required for social housing development on these sites.

Cape Town Mayor Geordin Hill-Lewis has emphasised addressing the affordable housing backlog as a key priority of his administration. Over the last year, the mayor has committed to fast-tracking the aforementioned inner-city land release process, touting progress made on the Salt River Market and Pickwick Road (two of the 13 sites identified in 2017) in July last year.

“I’m not sure we would be this far if we didn’t have DAG [Development Action Group] and Ndifuna Ukwazi in Cape Town,” said McCarthy. “I think their actions have been critically important in raising the issue and putting pressure on the municipality to actually act on it; whereas in other metros, certainly eThekwini, you don’t have anybody doing that, in Johannesburg maybe SERI [Socio-Economic Rights Institute of South Africa] but there’s a highly conflictual [relationship] between SERI and the Johannesburg municipality.”

Civil society groups and the social housing sector itself have expressed cautious optimism about these recent advances.

Ndifuna Ukwazi’s Aditya Kumar notes that there has been a lot of tangible progress on land release in 2022 but says that it is not yet clear whether this represents a broader, long-term shift in the City’s approach to the affordable housing issue.

“There seems to be quite a significant shift in terms of attitude, we just hope that this attitude percolates down into the institutions so that it’s not just Mayor Hill-Lewis who’s pushing this, but actually people in the administration who are very clear that this has to be a priority,” said Kumar.

Houston echoed this sentiment, stressing that sustained commitment is needed on the part of both the SHIs and the relevant government authorities to avoid further delays through the remaining steps in the development process.

“We have seen sites get released,” she said. “But I would not say we’re out of the woods because all these land release agreements that have been signed are contingent on those approvals being granted”.

Comparing his experience with their projects in Johannesburg to their more recent developments in Cape Town, Madulammoho Housing Association CEO Renier Erasmus told GroundUp that a more actively engaged municipality has a huge effect.

“The City of Cape Town has really said ‘we want to use the instrument of social housing to advance our housing goals in the city’, and that they have placed [it] in their housing directorate as a deliverable,” he said.

In addition to initiating contact about potential new projects, he says that the City of Cape Town has talked with Madulammoho about how they can make the development process smoother and has even been open to negotiating reduced utility tariffs to make new social housing developments more affordable. “I don’t find that same urgency in Joburg. In Joburg we have to fight for social housing,” Erasmus said.

McCarthy agrees with Erasmus, saying that in his view since 2017 Cape Town has made more systematic progress on social housing than any other municipality, within the role set for local government in the Social Housing Act and the regulator’s policies.

GroundUp sought comment from the eThekwini and Johannesburg municipalities on their approach to social housing policy but did not receive a response before our deadline. Nevertheless, the regulator’s reporting shows that Gauteng (and Johannesburg in particular) has outstripped the rest of the country in the volume of social housing both delivered and units in the planning pipeline.

For McCarthy, Erasmus and others, the City of Cape Town’s new approach in recent years is hastening the release of public land and attending to the problem of the spatial drift of social housing.

Long-term, the challenges facing the sector require coordinated action across all levels of government. Key actors in the sector believe that the City of Cape Town could set a valuable example of how to effectively tackle at least some of the problems at the municipal level if it continues to develop the proactive approach that it has been flirting with since 2017.

Published originally on GroundUp | By Maxwell Roeland