Reframing Women in Namibia’s Early History of Photography

Women photographers, and black African women photographers in particular, are largely absent from early histories of the medium. Even in South Africa, which has attracted more attention than other parts of the continent, few women photographers from the early and mid-1900s appear in the historical record. There are even fewer whose work has been collected […]

Women photographers, and black African women photographers in particular, are largely absent from early histories of the medium.

Even in South Africa, which has attracted more attention than other parts of the continent, few women photographers from the early and mid-1900s appear in the historical record. There are even fewer whose work has been collected and received serious treatment, like Constance Stuart Larrabee and Anne Fisher.

Women photographers in Namibia have languished in even greater obscurity, and scholarship that embraces this neglected history is only just emerging.

My new book Photography and History in Colonial Southern Africa: Shades of Empire explores ways to retrieve the histories lodged in these photographs.

The photos of Anneliese Scherz

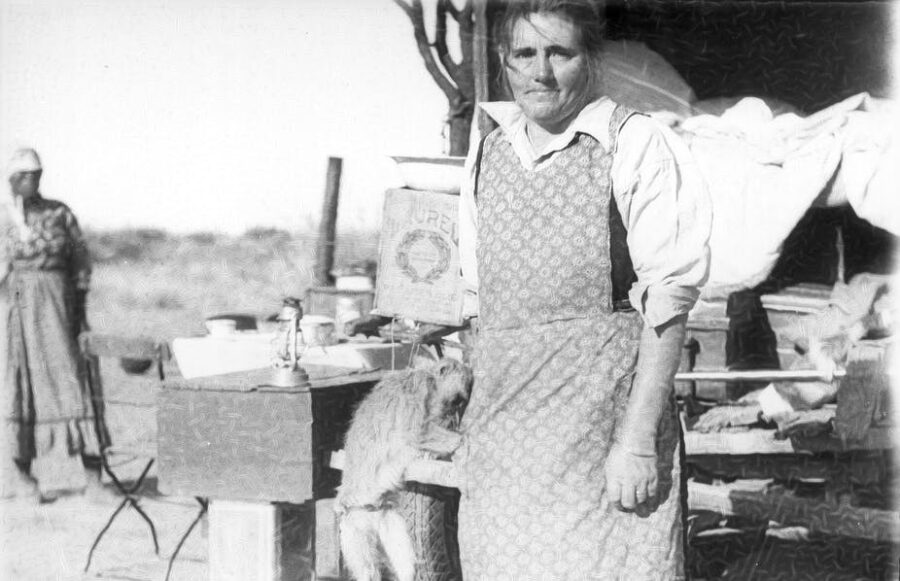

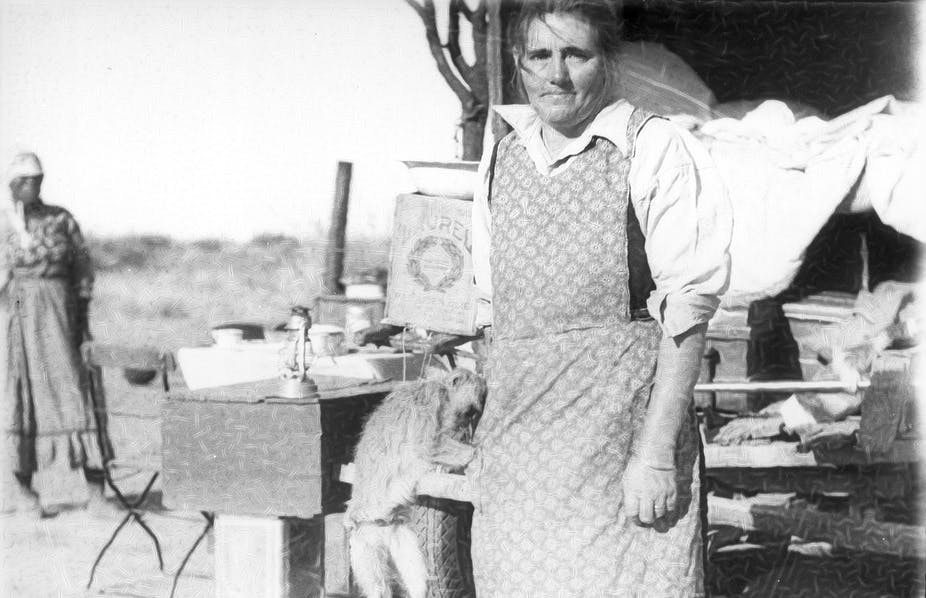

One of my chapters is dedicated to the work of Anneliese Scherz. Her photography in Namibia begins in the late 1930s and reaches into the 1970s. Across central Namibia in 1938, Scherz took photographs of white farmers of German descent, impoverished Afrikaners and black farm workers.

At the time, South African colonial rule in Namibia was firmly established and the politics of racial segregation prevailed. However, on the eve of World War II the region entered a period of political turmoil. Ethnic nationalism and partisanship threatened the unity of settler society. This was exacerbated by explicit sympathy for the fascist cause and colonial revisionism among settlers of German descent.

Scherz’s photography needs to be placed against this backdrop and understood as an attempt to imagine what lay at the heart of white consciousness in Namibia at the time. I argue that her photographs of German farmers and itinerant Afrikaners documented the harshness of white rural life in a way that fostered the viewer’s empathetic response. In contrast, her depictions of black farm labour in fact concealed the precarity and poverty it produced.

In other words, to Scherz, farm workers were not poor because of an exploitative colonial economy. They were poor because deprivation and scarcity were part of what she considered “native life”.

Her images invite us to engage white women photographers so that we can refine our understanding of how whiteness was lodged in the ways they looked at disenfranchised indigenous people.

And where black women’s agency was concealed by photography, it might have to be recovered or reactivated by opening confined spaces and asking about women’s multiple photographic practices, rather than merely focusing on the photographer as author.

The women photo collectors of Usakos

My reading expands the frame by juxtaposing the Scherz photos with the practice of black female photographers in Namibia at the time. I look at photos taken in Usakos, a central Namibian town, from 1910 up to the late 1950s when residents were forcibly removed to townships and the location destroyed.

The photos have been collected, preserved and curated by four women residents of Usakos. The work provides a window on an intricate history of women’s engagements with the medium.

The images tell of an African urban community’s encounters with black photographers who travel from place to place. The photographers came to central Namibia from as far as Cape Town and Johannesburg, moving along the railway lines to offer their services to people who didn’t have access to photo studios.

There are portraits of men and women in elegant attire and snapshots of everyday domestic activities in and around the location. There are weddings, funerals and baptisms, musicians with instruments, and men’s football and women’s netball teams lined up in a row.

Historical photographs can teach us about women’s negotiation of colonialism, apartheid and forced removals. And how the Usakos collectors understand their collections as a means to remember the past, negotiate the present and imagine their futures.

A question of representation

There is a long history of the exposure of women’s bodies in the colonial record, as well as of the production of images of racialised and sexualised women. The record raises questions about the politics and ethics of representation in today’s knowledge production.

Critical examinations of the colonial photographic archive, and the knowledge regimes it engendered, have been met by a desire to acknowledge women’s agency as photographic subjects. The last decade has seen the growth of historical studies of photography produced by scholars based in Africa. There are wide-ranging public contestations of dominant narratives.

One of the key concerns in both academic and public history contexts has been to address the tension between the heightened visibility of African women in the photographic record and their concurrent silencing in historical writing.

This tension possibly explains why numerous women academics, artists and activists continue to turn to the archive with the aim of dismantling an aesthetic order – one that notoriously put the black female body on display and fixed colonised Africans within gendered, racial and tribal categories.

This work is important, but we also need to keep in mind that there is a world of images beyond the archive. The Usakos old location photographs are an indication of how much this world of images was shaped by women.

This article by , a senior lecturer at the University of Basel, Switzerland, first appeared in The Conversation and is based on a chapter from her new book Photography and History in Colonial Southern Africa published by Wits University Press.