COVID-19: A Guide to Good Practice on Keeping People Well Informed

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is spreading across the world. For those who catch it, the vast majority will experience mild symptoms, but for a few, it can cause severe disease and death. Some groups – like older people and those with pre-existing health conditions – are more vulnerable when exposed than others. Because of this, […]

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is spreading across the world. For those who catch it, the vast majority will experience mild symptoms, but for a few, it can cause severe disease and death. Some groups – like older people and those with pre-existing health conditions – are more vulnerable when exposed than others.

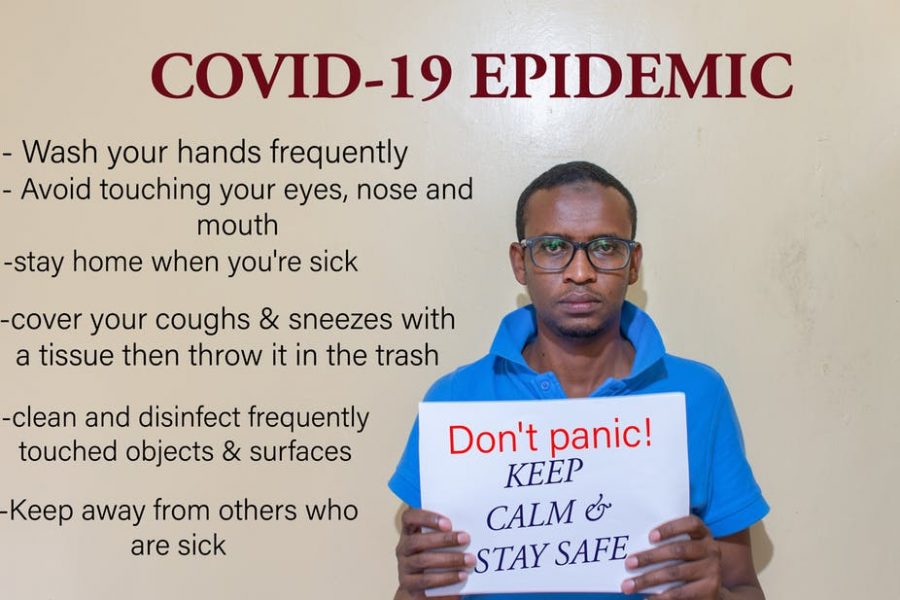

Because of this, the primary objectives in fighting the outbreak are to contain the virus and help the infected to get well again. In this context, health literacy is a valuable tool because it can affect health outcomes in multiple ways. Health literacy is the degree to which people can get, understand and use basic health information to make decisions about health issues.

A health literate society is one with a population that will be aware of the severity of the situation and is able to understand how to protect themselves, and others, through basic actions. In the case of this new virus, this includes physical distancing and washing hands. It’s also a society in which the systems and services in place can ensure clear, timely and appropriate communication.

In the current situation, well-informed individual behaviour is a key intervention alongside medical and governmental action. It’s crucial that health authorities apply health literacy principles and provide information that is easy-to-understand, easy-to-access, and barrier-free. Health literacy is vital to slowing down the spread of the virus and mitigating the impact and effects of COVID-19.

This isn’t always done well. In Europe, research has shown that health literacy is a neglected public health challenge. More than a third of the population faces difficulties in finding, understanding, evaluating and using the information to manage their health.

Another challenge is fake information. Instead of real facts, people’s information channels might be dominated by fake news and fear due to uncertainties. We’ve seen that during this pandemic – it’s not only the virus that is spreading quickly but “a wildfire of false and unverified information” on WhatsApp, Twitter, Facebook and other social media.

Along with more than 100 other health literacy experts, we put together a handbook on health literacy. This highlights cutting edge research, policy and practice from the field and is aimed at audiences from education, public health, health care and social science. Readers will learn about health promotion and prevention programmes for school children, patients, and the elderly. They can also learn about government and community policies that improve population health literacy.

What’s needed

Health literacy information must be understandable and it needs to meet the literacy needs of the people it’s directed at. People with reading difficulties, hearing and sight impairments, for example, will need different formats. They’ll need more explanation. For instance, animations help in explaining the virus, the disease, its transmission and protective measures.

For parents and children, the UN, UNICEF and Save the Children provide tips for how to talk to children about the virus. For example, comics might help.

Other criteria health authorities must keep in mind include:

- Explain the situation transparently and clarify the overriding objectives repeatedly to prepare people for the fact that interventions and recommendations might change based on new evidence and adapt to future scenarios.

- Be adaptable: information providers must be able to continuously communicate new evidence and information. Authorities should not be afraid to correct earlier messages and statements if new information is available, especially if it is contradicting yesterday’s news.

- Avoid a blame game: blaming false security promises and scandalous over-interpretations of studies and figures are of little help. Rather, the aim should be to strengthen the well-informed responsibility of the individual, solidarity with particularly vulnerable population groups and targeted collaborative action.

Linked to this is the need to prepare people for a barrage of misinformation. Health literacy can apply some basic principles that ensure people get the right information and know-how to distinguish the bad.

This will:

- Help people cross-check the accuracy and credibility of information found on TV, radio, internet, and social media, including aggressive ads for products.

- Enable people to ask questions to family members and trusted health professionals about the fake news, misinformation and harmful content and messages.

- Guide people to evidence-based messaging. As the Global Working Group on Health Literacy of the International Union for Health Promotion and Education stated, “the dissemination of quality, timely and understandable information is key in slowing down transmission and avoiding overburdening the healthcare system”.

- Encourage people to check the source of information (where does it come from, who is behind the information, what is the intention, why was it shared, when was it published)

- Encourage people to search a second source verifying the information and to double-check with family, friends, colleagues and trusted health professionals

- Encourage people to think hard before sharing information and not to share anything they haven’t checked and to visit fact-checking websites. These include credible sites such as the News Literacy Project, their fake news check questionnaire and CUNY’s Graduate School of Journalism’s fake check guide.

If followed, some of the information and guidelines we’ve set out in the handbook can go a long way to building citizens’ health literacy on COVID-19 and contribute to containing the disease.![]()

Orkan Okan, Researcher, Interdisciplinary Centre for Health Literacy Research, Bielefeld University; Kristine Sørensen, Director, Global Health Literacy Academy and Associated Guest Researcher, Freiburg University, and Melanie Messer, External Lecturer, APOLLON University of Applied Sciences

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.