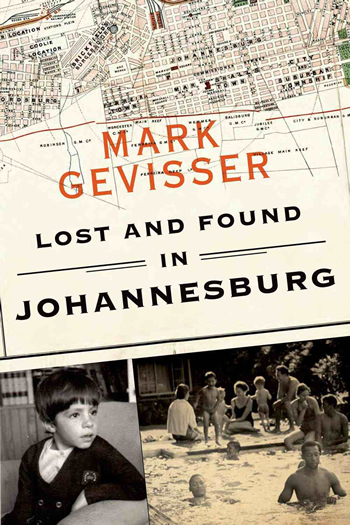

Lost and Found in Johannesburg

I must confess that I’d never read much of Mark Gevisser before someone at work in New York brought me this book because it had Johannesburg in the title and I was a South African. They thought I’d relate. Which I did, except it was more to the title than to the author. At last, […]

I must confess that I’d never read much of Mark Gevisser before someone at work in New York brought me this book because it had Johannesburg in the title and I was a South African. They thought I’d relate.

and Peter Gevisser. Courtesy of the Gevisser Family

Archive.

Which I did, except it was more to the title than to the author. At last, a book about Johannesburg, the city that many of us feel has always gotten a raw deal, the thin edge of the wedge, as we used to say, ignored by outsiders, avoided by visitors, baptised the crime capital of the world by travel agents who have never been there. Yet it’s managed to pull itself up by its bootstraps and defy the insults and the naysayers time and time again.

I remember my own ambivalence about moving from Pretoria to take a job in Johannesburg in the 1980s. Dusty, mine dumps, nothing much to recommend it (at least that’s what you were led to believe), until the day I was driving along Yeoville Ridge and discovered this was a city with heartbreaking views, a canopy of mauve jacarandas in November, thrilling thunderstorms. Then I stumbled on Munro Drive, got lost out near Gold Reef City, and began exploring Fordsburg and Brixton and Troyeville. It didn’t take long to fall in love with this city that pulsed to a beat quite unlike any other in the world. As I read Gevisser’s book, the extremes of Johannesburg returned to me afresh, and I for some reason couldn’t help thinking of George Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London.

So much for the place, but of Gevisser I knew little. In truth, I thought he was an American who had moved to South Africa in the 1990s and began writing for the Weekly Mail, a paper I already was finding hard to read because of stories that seemed to go on for way too long. Besides that, how dare an American come to South Africa after all we’d been through – finger-wagging PW, sanctions, I Ain’t Gonna Play Sun City – and write about our peccadilloes and tell us how we should live? The gall of the man! Then, of all things, he started writing stories about gay rights, as if he had an agenda or something. What a loser!

Turns out the loser was me, and for a couple of reasons.

First of all, Gevisser was actually born and grew up in Johannesburg at the same time that lots of us did, and was also dealing with his own perplexing version of a Childhood in the 1970s. Suddenly, instead of Gevisser being a foreigner, he was my compatriot, leading me down Memory Lane, causing me to think about my own childhood in Pretoria, Roman Catholic, half-Afrikaans, relating more to the Jews, Poles, Madeirans, Greeks and other outsiders despite being white, where we had Chinese boys in class who were classified black but were our friends and spoke just like us, and my sister and I spent hours in the maid Daphne’s room out back that reeked of Lifeboy soap, sitting atop her bed that was on bricks because of the evil, night-invading tokolosh. These were everyday things to us that even more so today it’s hard to explain to foreigners.

Gevisser, meanwhile, was born Jewish in Sandton, went to King David and then Redhill and Wits, discovered he was gay at a young age, hung around (probably a bit too much for his own good, as you’ll see as you get into the book) Estoril Books and the Three Sisters Cafe in Hillbrow, an area he sketches with loving detail, and then instead of doing military service fled to America, where he studied at Yale. (Yes, he’s a clever chap this.) When he landed in South Africa in 1990, it was not as an American, as I’d thought until now, but as someone returning home.

The second way I’m a loser is in having missed out on Gevisser’s writing. Because, brother, can this guy write. From the moment he starts off his story, a young boy paging through his Holmden’s (an odd precursor to Map Studio I’d never heard of) and playing a game with maps he called Dispatcher, trying in vain to make sense of his patchwork city, where adjacent suburbs didn’t connect but were left stranded on a page (think Sandton versus Alexandra), you immediately know that this is someone you want to have at the wheel.

And suddenly you are in a flat in Killarney where a terrible crime is about to take place, then in Lithuania tracing your roots, then on Clifton Beach with his parents in a childhood oblivious of the harsh country around you, then at Stellenbosch University where your father is singled out for being a Jew, then in Braam Fischer’s swimming pool where nonwhite people are swimming and it’s 1965, and then you are in Hillbrow Cemetery looking for your ancestors, then you are talking to a black man who is ashamed of the fact that he and his longtime black boyfriend both have wives and families. It’s all a rollercoaster ride of many rises and falls, memories and a lot of ace reporting.

Led by maps, Gevisser takes you on this ride, not only through Johannesburg but through a history of the city and South Africa whose nuances you sometimes can’t believe, even though you might have lived through them yourself. And it leaves you feeling simultaneously proud and humiliated, thrilled and disgusted, but never does it make you cringe.

Led by maps, Gevisser takes you on this ride, not only through Johannesburg but through a history of the city and South Africa whose nuances you sometimes can’t believe, even though you might have lived through them yourself. And it leaves you feeling simultaneously proud and humiliated, thrilled and disgusted, but never does it make you cringe.

Here, I kept thinking, is a book that does not only the city justice, but South Africa, telling a sometimes very personal story – the good and the bad, and there are bad people on both sides whom he doesn’t shy away from – the way many of us have been waiting for it to be told. It shows up our heart and our warts in equal measure.

Not even Gevisser can make sense of it all the time, but the map he lays out is rich with detail, characters, anecdotes, and always his great style. Taking a random quote from any book doesn’t really convey the impact of what goes before and after it, but let me do it anyway. “I have lived a life in Johannesburg,” Gevisser writes. “I have left the suburbs. I have put my body in those places I dreamed of. And yet I have found, to my perpetual surprise, that my hometown eludes me, however assiduously I court it.”

One scene in particular that Gevisser writes about sticks out in my head, and it’s of a party being held in a flat in Hillbrow in the 1960s, a gay party that you could only imagine was quite raucous, and some of the participants are out on the balcony. Their view was of the Old Fort, the jail that is now Constitution Hill, where black men (many of whom were arrested for pass offences) were, as a form of punishment, made to dance naked in front of their fellow inmates. On one side of Clarendon Street were men doing something illicit for fun, on the other were men being shamed after having been arrested for doing nothing more illicit than being black and in the wrong place at the wrong time.

There are so many things that Gevisser writes about that others have written about before him – the shameful arrests, the forced separations, the shootings, the crime – but then there is also the joy, the trysts we never knew about, the people who lived life despite apartheid.

In the end, Lost and Found probably leaves you with as many uncertainties about South Africa and Johannesburg as you started out with, except one. You love the city even more.

Lost and Found is published by Granta in the UK, Farrar, Straus and Giroux in the U.S., and Jonathan Ball in South Africa – www.jonathanball.co.za/