Following in Burchell’s tracks

I found it! I found the remains of the hut that sheltered explorer and naturalist William Burchell on the final leg of his journey to Graaff-Reinet in 1813. Burchell, the quintessential Renaissance Man, was one of the more celebrated of the early explorers who visited South Africa in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. […]

I found it! I found the remains of the hut that sheltered explorer and naturalist William Burchell on the final leg of his journey to Graaff-Reinet in 1813.

Burchell, the quintessential Renaissance Man, was one of the more celebrated of the early explorers who visited South Africa in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. He left vivid accounts of life in the colony, of the Hottentots and Bushmen he came across, and of the fauna and flora of the Karoo and Western Cape.

He arrived in Cape Town on a boat from St Helena in November 1810, aged 29, and left on his journey seven months later, travelling beyond the border of the colony, right up to Kuruman in today’s Northern Cape, before making his way back along the coast to Cape Town four years later, arriving in April 1815 after travelling 7 242 kilometres. He documented his travels in two beautifully written volumes, published in 1822 and 1824. A third volume was never written, so we have an unfinished tale of his travels in South Africa but a complete map of his route.

I found the remains of Burchell’s hut on a recent mountain biking trip with several friends. We drove down to Graaff-Reinet in Eastern Cape, to re-enact Burchell’s return trip from there to Griquatown, a village in Northern Cape, then known as Klaarwater (meaning “the end of water” in Afrikaans).

Burchell describes the hut: “It consisted only of one room; part of the roof had been blown off; the floor was covered with the rubbish of the thatch which had fallen in; and the door and windows had been taken away.” He had felt a fever developing so was happy to have found shelter, even if it was makeshift.

He had left his two wagons in Klaarwater and travelled on horseback down to Graaff-Reinet where he was hoping to recruit more men to travel further north with him. He had been advised that he wouldn’t survive the tribes living beyond the border, where previous expeditions had gone, never to be heard of again.

Just before he reached Graaff-Reinet he took ill with influenza, some 16km north of the town, and sheltered in the hut for a few days. He wrote that 6 000 people in Cape Town had been afflicted by the flu. The hut was on the old dirt Ouberg pass road, now running through Philip Kemp’s farm Brakfontein. I don’t believe anyone has tried to find the hut before, but careful mapping of his route pointed to the farm.

Kemp was intrigued to hear about the location of the hut and willingly drove me some 500m up the old pass until we spotted an old kraal. Opposite it was the hut, now just a rectangle of untidy low rock walls, with the rocks scattered around. One corner retains rocks cemented together a metre high. The farm has been in the Kemp family since 1966, where they farm sheep, goats and cattle on 3 000ha. He says the farmhouse is “very old”, and is happy for people to visit the hut site.

Burchell described the hut again on his way out of Graaff Reinet: “As I passed my hut, I silently thanked it for the shelter which it had so opportunely afforded me; and without which, the fever might possibly have gained a fatal ascendency.”

Burchell was somewhat amused by rumours that he was leading an army of 300 Hottentots to attack Graaff-Reinet, “taking advantage of the favourable moment when so many boors were absent from their homes and detained on the commando in the Zuureveld”. The villagers’ concern was exacerbated by the recent death of Commandant Stockenstroom in skirmishes with the Bushmen. Several people from the town visited him in the hut, urging him to return with them, but at the same time checking to ascertain the size of his “army”.

Finding the locations

We had set ourselves the goal of finding some of the locations Burchell had drawn in his sketches. The first one was easy – the Drostdy in Parsonage Street in Graaff-Reinet is still there, looking just as he drew it.

(Images: William Burchell)

About 30 kilometres north Graaff-Reinet is a spectacular waterfall. Although not in either of his volumes, he did draw the waterfall, and this peaceful place is worth a visit. And unlike Burchell, you can pull in to guesthouses along the way and experience great Karoo hospitality: 70 kilometres outside Graaff-Reinet is Lynne Minnaar’s Groenvlei guesthouse. She offers warm-hearted friendliness on her farm, with lashings of lamb and healthy vegetables, and malva pudding. On our first night we had dinner by kerosene lamp in the old shed, with farm implements

and historical artefacts on the walls.

The next day involved another search, this time for Burchell’s initials, WJB – William John Burchell – which he scratched on to a rock on a koppie on the farm Brandfontein, 10km outside De Aar and belonging to Ian and Igme Strauss. On a previous trip we had searched

the koppie behind the farmhouse at Brandfontein, and although we found a number of rocks with

initials scratched on them, none corresponded to what we were looking for. I looked again for the initials on this trip, but could not find them. Perhaps it’s not the right koppie.

The farmhouse is typical of many in the Karoo – sprawling and solidly built, with warm fireplaces and wonderful views. Strauss says the guesthouse dates back to 1820, while the farmhouse was built in 1860. Nearby is the shearing shed, a long, wooden-strutted room where over the years many sheep have given up their wool.

Personable and unassuming

Burchell, a short man at 1.62m, was personable and unassuming, and wrote eloquently of his love for South Africa. He learned to speak Dutch while in Cape Town, and spoke to his Hottentot companions, Speelman and Juli, who accompanied him on his travels, in Dutch. He was immensely talented: he could draw and paint; he could play several musical instruments; he had an understanding of science, in particular flora and fauna; and he had an easy manner with people, at once putting them at ease while enquiring about their wellbeing.

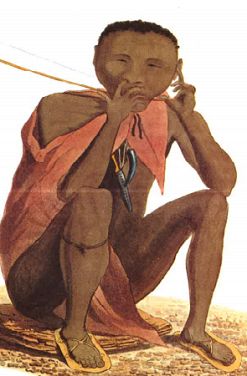

His powers of observation were exceptional, as his drawing and description of a Bushman arrow show: “The shaft is made from the common African reed, and at each end is neatly bound round with sinew, to prevent splitting. The head consists principally of a long piece of bone cut very smoothly to fit exactly into the reed, so as to remain fast without being absolutely fixed. The length of the whole arrow is generally between eighteen and twenty-two inches.”

His legacy can be found in many names: Burchell’s zebra; eciton burchellii army ant; burchellia bubilia, a wild pomegranate; Burchell’s coucal, starling, courser and grouse; and Burchell’s sand lizard. He was the first to describe the white rhino near Kuruman in 1812.

Before he left Cape Town he had a wagon made to his specifications. It had to accommodate 50 scientific reference books, his flute, his drawing materials, his bed, his specimen boxes, his work desk, rifles and ammunition, a medicine kit, and items like snuff and beads to give as gifts. But shortly after leaving Cape Town he discovered that one wagon was not sufficient, and bought another one. By the end of his trip he had collected 60 000 natural history specimens, mostly botanical but also numerous animal skins. He returned too with 500 drawings, including valuable portraits of locals, landscapes and illustrations of botanical and zoological subjects.

But perhaps his more enduring legacy is the map of his travels. It not only follows his route carefully but is annotated, showing intriguing details of places he named, animals he first came across, and people he met. The map reflects local Hottentot or Dutch names – he was always respectful of names already given to places, and never replaced them with Eurocentric ones, like other explorers did. For instance, he referred to the Orange River as the Gariep River, the original Hottentot name.

Born in London

Burchell was born in London on 23 July 1781, the son of the prosperous owner of the Fulham Nursery, a nine-and-a-half acre stretch of land neighbouring Fulham Palace, the residence of the Bishop of London, on the north bank of the Thames. He studied botany but turned down an offer by his father to work at the nursery, instead sailing to St Helena, where he was to join in a partnership as a merchant. But after trying this for seven months, he discovered it wasn’t his calling, and was appointed temporary schoolmaster on the island.

Before leaving England, he wished to become engaged to Lucia Green, but his parents disapproved of the match. But in time they came around to the idea and she left for St Helena on board the Walmer Castle, reaching the island in April 1808. But the marriage didn’t take place – Green “transferred her affections” to the captain of the ship, explains A Gordon-Brown in the introduction to the 1967 edition of Burchell’s volumes.

He was never to marry, and perhaps would never have undertaken his explorations in South Africa if he had.

Arrival in Cape Town

He was subsequently appointed naturalist on the island but in October 1810 he decided to sail for Cape Town. He had been in correspondence with Reverend CHF Hesse, the Lutheran minister in Cape Town, where he stayed when he arrived in the town. The Lutheran church is still standing, in Strand Street, much as it was in Burchell’s day, and is worth a visit.

Hesse’s home next door still stands but is now the Gold of Africa Museum, also worth a visit.

Burchell’s trip to Klaarwater was undertaken with missionaries, but all his other journeys were with just his Hottentot servants. The most northerly point he reached was Litakun, an extraordinary sprawling Tswana settlement some 20km north-east of Klaarwater. Traces of many cattle kraals can still be seen in the area, a hint of how large the settlement was.

He stayed in Litakun for several weeks, and then made his way to Grahamstown, where he stayed for five weeks, before leaving for the Fish River mouth, visiting Kowie, Uitenhage, Port Elizabeth, and the villages along the coast to Cape Town, where he arrived in mid-April 1815. He returned to England that year, arriving in November.

Several years after his return, he was asked about sending British settlers to the Cape Colony. He compiled a report in 1819, recommending the Port Elizabeth and Grahamstown areas – and this report led directly to the 1820 settlers being sent out to farm in the Cape.

(Images: Lucille Davie)

He went to Brazil in 1825 and returned in March 1830, but the only published account of that journey is two letters – his journals were lost. In 1834, the University of Oxford conferred on him a Doctorate of Civil Law honoris causa, the only public recognition he received. He became increasingly isolated as he aged and in a fit of despondency, hanged himself in Fulham on 23 March 1863, at the age of 82.

His botanical collections, drawings and manuscripts, from South Africa and Brazil, went to the Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew; the entomological collections, drawings and notebooks went to the University Museum, Oxford. Some 557 landscapes and portraits are in Museum Africa in Johannesburg, and a few are in private collections.

A night under the stars

We decided to spend a night camping in a river bed, just like Burchell had done throughout his trip. We had permission from a farmer to camp on his farm, and were to be minimalist and rolled out our sleeping bags on the soft sand. We collected branches from the surrounding bush, and soon had a two-metre high fire blazing into the night sky.

Once it had died down, we placed our lamb chops – surely Burchell would have braaied them, too? – on the coals, and were soon munching them with rolls. The evening was overcast but I remember waking in the night to a star-filled sky, and I’m convinced the stars willed me awake, to show off their splendour.

We woke in the morning to rain on our faces – Burchell had spent odd nights trying to sleep under an umbrella in the pouring rain. At least the rain waited till the morning for us, and it didn’t last. It was time to get up anyway, and within an hour we were ready to swing a leg over our bikes, ready to start another day of following in Burchell’s tracks.

The Gariep River

We took our leave of Burchell at the Gariep River. He wrote in his second volume: “This day’s march brought us once more to the delightful woody banks of the beautiful Gariep. I hailed its airy acacia groves and drooping willows, and derived pleasure from fancying that they waved their branches to bid me welcome again to their cooling shade, and to greet me on my safe return.”

Crossing with the large party he had gathered along the way, including a dozen sheep and about 20 dogs, became a huge undertaking, with some of the party left to spend the night on an island in the river.

When they had all finally assembled on the other side of the swollen river, Burchell observed: “My men were in not less alarm: all preserved a fearful silence as long as they were in the water, which was between ten and fifteen minutes; but the moment we reached the shore, they congratulated each other on having landed without incident. Old Hans, who was near me and had observed my horse stumbling and scarcely able to stand against the force of the current, exclaimed very fervently when we gained the bank; ‘Thank God! Mynheer is safe’.”

Our crossing of the Gariep was a lot less dramatic. We had charted where we guessed Burchell and his party had crossed, and the eight of us ran down the bank to a sandy stretch. Not deterred by the April chilliness, two of our party got down to their underpants and waded in to knee-high water. They crossed the tip of an island then walked into the deeper section, finally becoming immersed near the opposite bank.

They disappeared from sight but when they returned, their faces carried broad smiles of satisfaction – they had crossed the Gariep, like Burchell had done.

We didn’t feel a need to go on to Klaarwater, perhaps another time. We loaded the bikes on to our vehicles and headed for home.

By: Lucille Davie

Source: www.mediaclubsouthafrica.com