Happy 170th Birthday Bloemfontein – From British Spy Post to Judicial Capital

Bloemfontein, situated in the middle of the bucolic countryside of the Free State in South Africa, was originally a British outpost in an area of turbulent warfare. The history of Bloemfontein is inexorably linked to the complex history of the now-named Free State province of Africa. And the history of the Free State in the […]

Bloemfontein, situated in the middle of the bucolic countryside of the Free State in South Africa, was originally a British outpost in an area of turbulent warfare.

The history of Bloemfontein is inexorably linked to the complex history of the now-named Free State province of Africa. And the history of the Free State in the 1800s is fraught with cultural clashes, skirmishes, battles, victories, wars, surrenders, betrayals, peace treaties and conventions. To understand the reason why Bloemfontein was founded in 1846 one must step back a few centuries.

About 250 years ago the unexplored area north of the Orange River was called Transoranje by Dutch hunters from the Cape. When Great Britain took over the Cape as a Colony in 1806 the northern boundary of the Cape Colony was the Orange River.

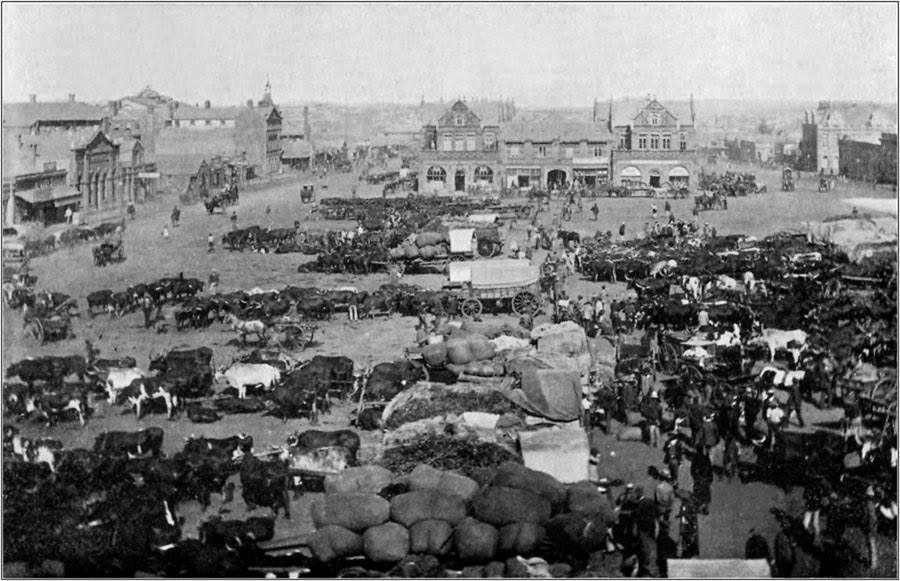

The first modern occupants of the area between the Orange and Vaal rivers in South Africa were the Khoi-San. This region had an abundance of permanent water sources and a profusion of game, making it an ideal hunting ground.

Today one can see examples of the Khoi-San rock art in various places in the Free State. One such place is the Slypsteenberg, which is now within the city limits of Bloemfontein.

The National Museum of Bloemfontein houses a number of these paintings, but its most prized item is the Florisbad skull, found in 1932 at Florisbad in the Free State. Classified as Homo sapiens the skull is about 260,000 years old, and is one of South Africa’s paleontological gems.

More recent arrivals were migrants from the Congo River basin, who reached southern Africa about 2,000 years ago. They encroached on the Khoi-San territory. The Khoi-San local were forced to move into more arid areas. One migrant group, now known as the Basotho, settled on the fertile eastern area of Transoranje.

Clearly people have lived in the region for a very long time. However, it is the inhabitants of the 19th century – clans, refugees, invaders and migrants — that are particularly relevant to the founding of Bloemfontein.

The story of Bloemfontein begins in 1820 when the region became fraught with brutal battles, massacres and cannabilism.

Clan inhabitants

In 1800, most people living in the area just north of the Orange River belonged to one of three main Sotho groups – the Fokeng, the Koena or the Tlokoa. Each group consisted of a number of clans, with each of these under the leadership of a chief. The valley of the Caledon River, a tributary of the Orange River, was a prized location. It had exceptionally fertile soil for crops and good grazing, and could be farmed without irrigation.

Whenever a seasonal drought occurred, crops would fail, followed by famine. Raiding cattle and grain stores was then vital for survival; only occasionally were people killed.

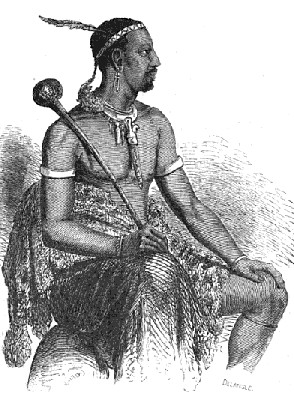

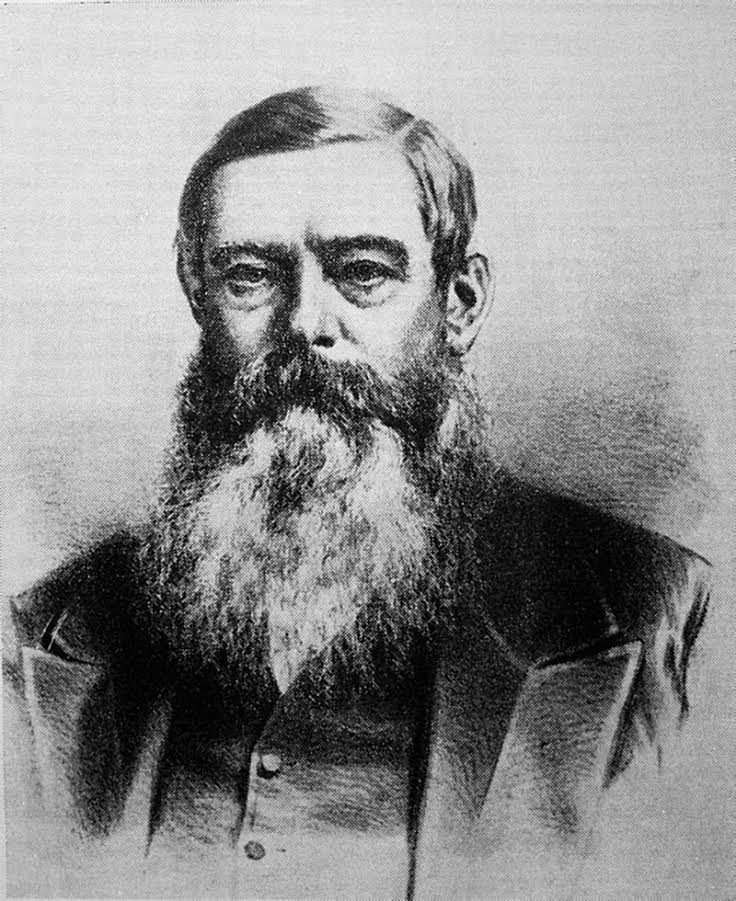

From this background an outstanding leader emerged: Moshoeshoe. He was born near the Caledon River in 1787, the son of the head of the Bamokoteli clan. He died in 1870.

Moshoeshoe

At an early age Moshoeshoe was a skilled negotiator. In his 20s he left his father’s clan and set up his own village. He started to assign fertile land to the local clans to reduce raiding. By 1820 he had united some clanlets into a larger clan by allocating some good land to them as an alternative to raids. This was the beginning of the Basotho nation.

All his life Moshoeshoe sought peaceful solutions, but ultimately only obtained it at a great price after decades of warfare. He is probably the Free State’s greatest hero, a forerunner of another man of peace, Nelson Mandela.

The tranquillity of the valley was shattered in 1821 when Zulu clans fleeing from the Zulu King Chaka’s ferocious army started arriving in the Caledon River valley. Chaka was intent on land expansion and his warriors would kill any clans who tried to resist them. Refugee clans kept on arriving … and stayed. They spoke Zulu, not Sotha.

The difaqano

Competition for resources in the fecund Caledon River valley increased, resulting in a multitude of inter-tribal battles quite unique in Basotho history. A ghastly series of massacres occurred which produced no tangible results and reduced the peace-loving local clans to a state of abject misery. Known as the difaqano – the crushing or scattering – this 15 years long war resulted in the total annihilation of 28 clans. In extremus people resorted to cannibalism.

Through a series of strategic moves Moshoeshoe and his people survived these dreadful decades. In time they were joined by a motley rabble of war weary warriors, starving women and children, and bands of cannibals. Moshoeshoe accepted all of them into his growing tribe.

In 1824 Moshoeshoe moved to the top of the impregnable mountain fortress of Thaba Bosui. By 1829 about 5,000 people and their livestock were living there. Several water springs on the plateau sustained them, as well as food supplies stored there by Moshoeshoe.

Thaba Bosiu – mountain of the night – is a sandstone plateau that is 400m above the plain. It rises up so steeply that the top can be reached only by paths. This made it easy to defend. The flat top has an area of approximately 2km². It is located between the Orange and Caledon rivers, east of the present day Lesotho’s capital, Maseru.

In 1831 the powerful Mzilikazi, King of the Ndebele in the north, added to the chaos by sending battle troops to the area. The loss of life was appalling. However they were unable to assail the plateau of Thaba Bosui.

Over the next 50 years there were many attacks on this mountain stronghold, but no one ever succeeded in conquering it. In later years Moshoeshoe referred to Thaba Bosui as his ‘mother’.

More migrants arrive

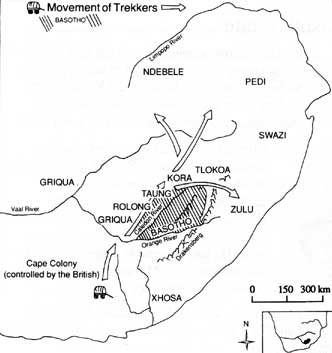

Other arrivals from the Cape Colony added to the turmoil. And all crossed the Orange River where it was narrow and could be forded. Hence they all arrived at the same area, between the Orange and Caledon rivers.

The brigand Hendrik Hendriks headed up various bands of mixed-descent thugs known as the Koranna and they settled in the Caledon River area. They owned guns, never seen in the area before. Next to arrive were a group of nomadic Griquas from the Cape, a differently mixed-descent people with Khoi-San links. They also had guns. They ultimately moved west, out of the contested territory.

The turbulence of the difaqano increased with the new arrivals.

Moshoeshoe continued negotiations with relevant parties throughout the difaqano, trying desperately to restore peace, and he became well known to many.

By 1840 the Fokeng and the Koena chiefdoms were voluntarily under Moshoeshoe’s control and he was chief of 50,000 people. He had become so important that he was addressed as Morena oa Basotho (Chief of the Basotho).

Trekboers and Voortrekkers

Nomadic Dutch and ‘coloured’ farmers from the Cape, known as trek-Boers, had settled in Transoranje since 1800. During the difagano they also experienced cattle raids, but they had guns for protection. With help from them Mzilikazi’s army was eventually defeated.

A common story is that the trek-Boers who arrived in the late 1820s saw a country littered with human bones.

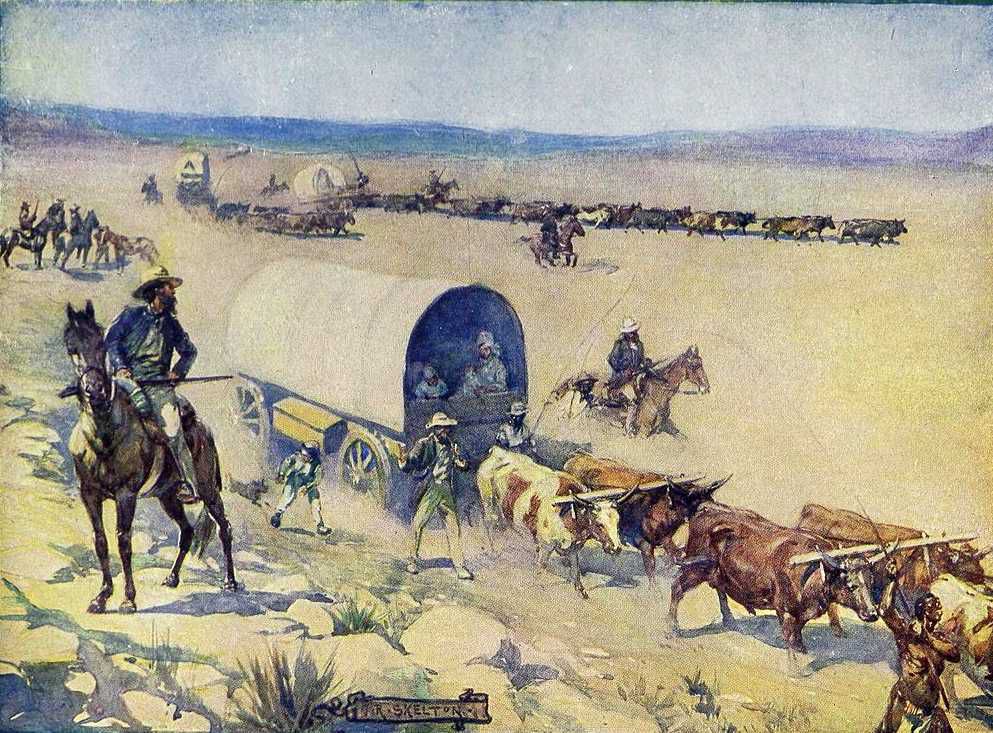

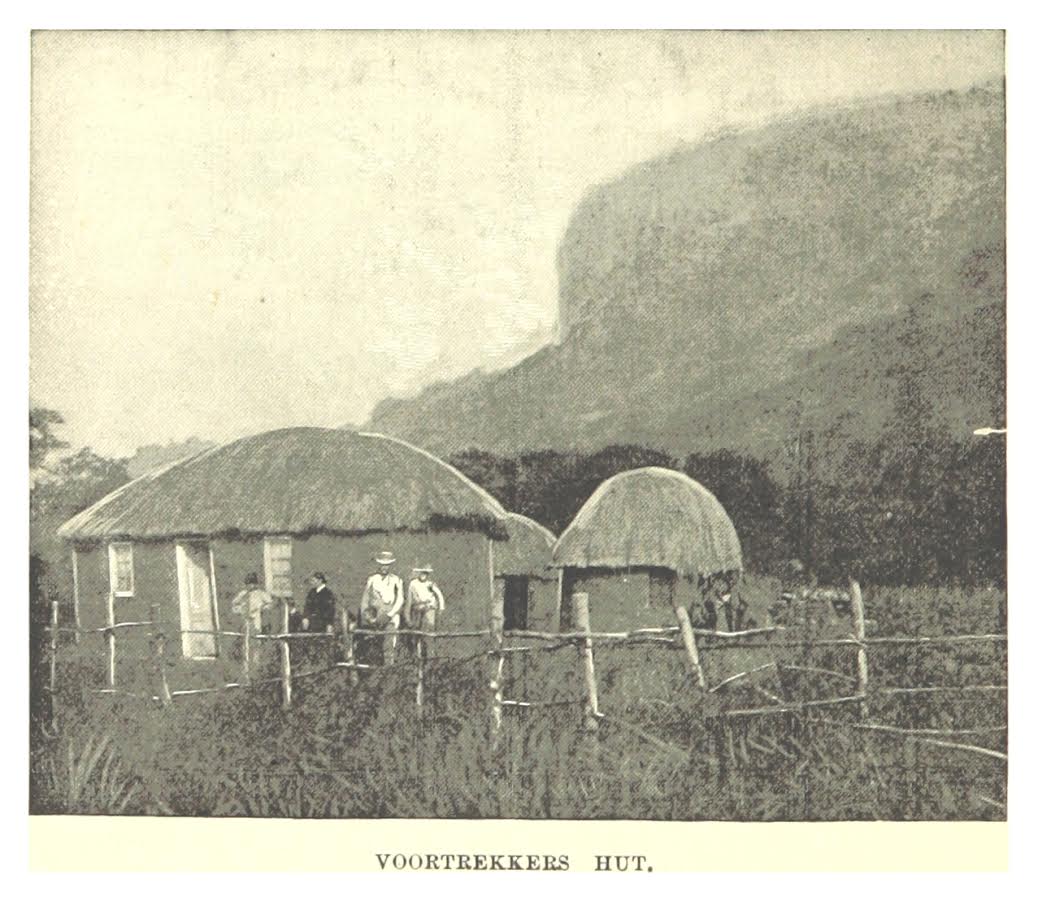

The Voortrekkers — ‘going before people’ – comprised Dutch inhabitants in the Cape Colony who resented British rule. After a series of unsettling events they left the Cape Colony in 1836 to settle in the non-British Transoranje area, or further north. There were 12,000 people in this mass migration.

Many went north beyond the Vaal River. Some settled in the north of Transoranje, with permission from a local chief. They established Winburg, the first town in Transoranje. Another group settled near the Caledon in territory that Moshoeshoe regarded as his own.

The arrival of the Voortrekkers led to violent territorial disputes between them and the Basotho clans, particularly in the Caledon and Orange river valleys. Raiding and retaliation and outright wars continued for the next 30 years.

After hearing of the benefits missionaries brought, Moshoeshoe invited missionaries to settle at Thaba Bosui. Three arrived in 1837.

One in particular, the Frenchman Eugene Casalis, became a great friend and advisor. With his knowledge of the non-African world, Casalis was able to inform and advise the King in his dealings with hostile foreigners and act as interpreter. King Moshoeshoe now dressed formally for negotiations.

To prevent the invasion of his part of the country by Boer farmers, Moshoeshoe asked the British Governor of the Cape to settle land issues in the Caledon River valley.

In 1838 the Cape Governor Napier and Moshoeshoe signed Napier Treaty, which recognised most of the territory that Moshoeshoe claimed.

It included land occupied by the Rolong, the Taung, the Kora, the Tlokoa and the Boers. The problem was that the Rolong, the Tlokoa, and the Boers were not prepared to accept Moshoeshoe’s authority.

For the sake of peace, Moshoeshoe finally agreed to make a section of Basotho land in the triangle between the Orange and the Caledon rivers available to the Boers. The Boers could rent, but not buy this land. This did not satisfy the Boers, and tensions grew. By now, through trade with the Boers, Mashoeshoe was able to acquire guns and horses.

The ensuing conflict throughout Transoranje was the reason why Bloemfontein was founded.

The Founding of Bloemfontein

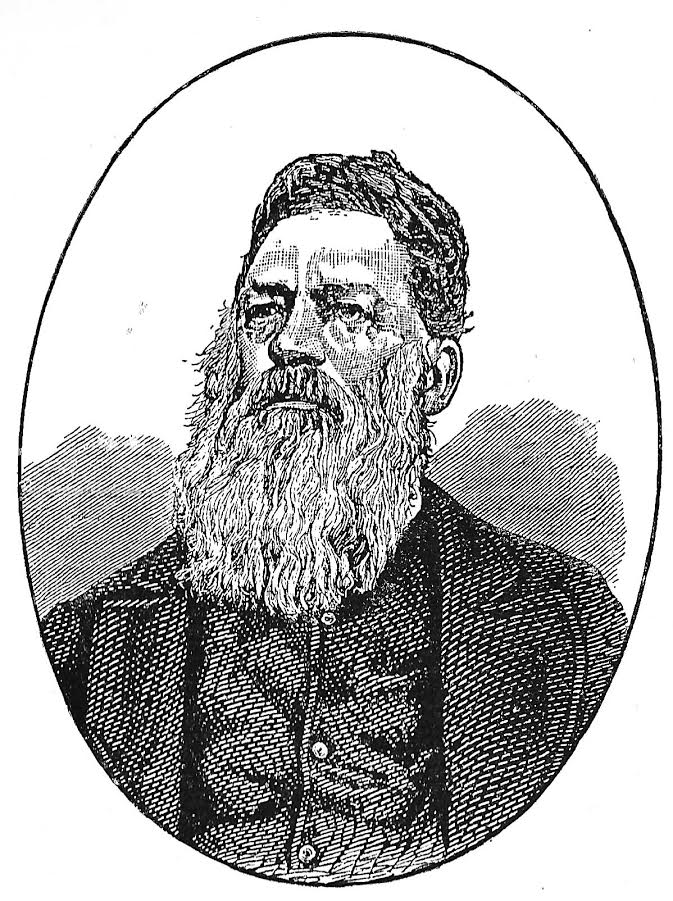

In 1846 the then Governor of the Cape Colony, Sir Peregrine Maitland, sent the British Army major Henry Warden to establish a British Residency in a centrally situated place in Transoranje between the areas occupied by the Griquas in the west and the Basotho in the east. He was tasked with the difficult job of maintaining peace between the different population groups.

Warden accidentally came across the fountain area between the Riet and Modder rivers. From a military point of view, he found the area suitable because it was situated in a small valley surrounded by hills on all sides and was free of horse sickness.

The chosen place was on the farm ‘Bloemfontein’, established by trek-Boer Johan Brits. He had selected the area because it had a fountain. Local people called the place Mangaung, the place of the cheetahs, so originally it may have been a meeting place for hunters.

There is some controversy surrounding the name ‘Bloemfontein’. One theory is that when Brits settled here, the fountain was surrounded by flowers and thus named it Bloemfontein, literally meaning ‘fountain of flowers’.

Today the metropolitan municipality which governs Bloemfontein and surrounding towns in the Free State province is called Mangaung.

At the time the farm consisted of a small mud house with a garden in the front and an orchard which was watered through a furrow. It became the British Residency in Bloemfontein and home of Major Henry Warden.

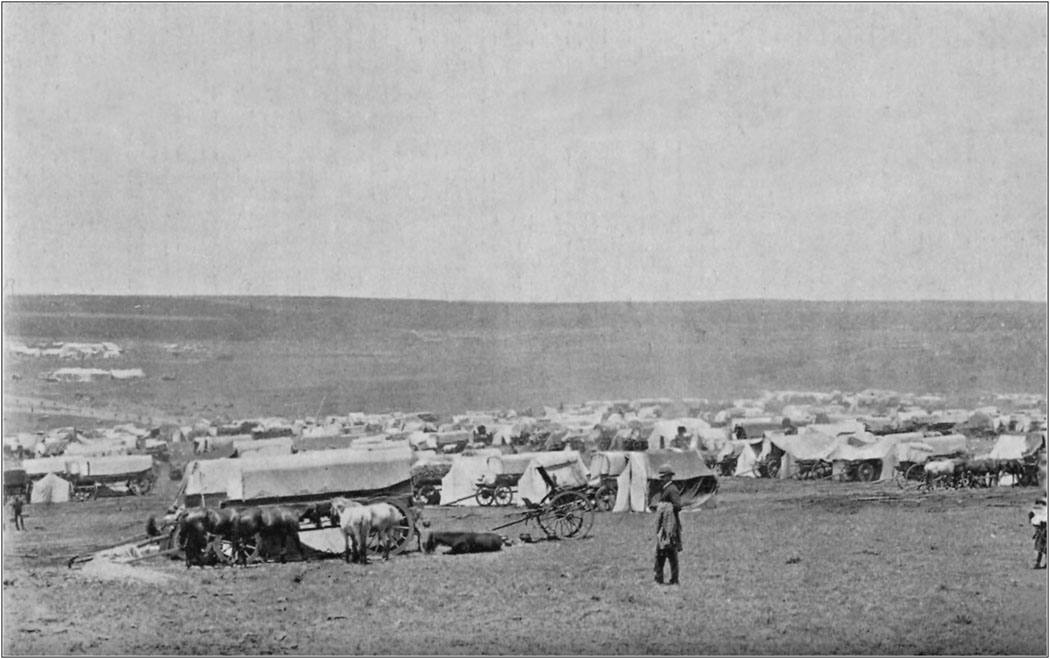

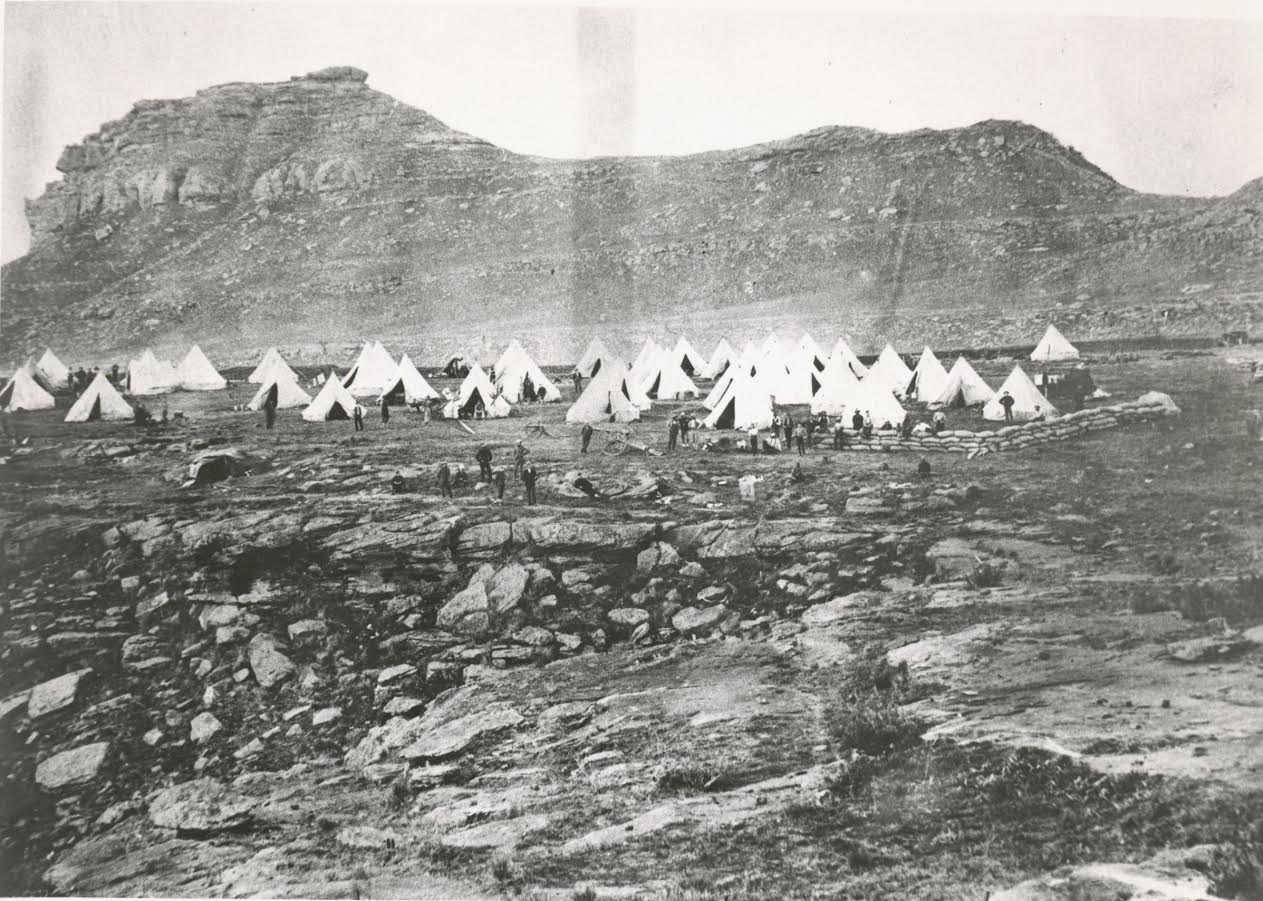

Warden’s troops, known as the Cape Riflemen, arrived in Bloemfontein on 26 March 1846. Thus was Bloemfontein officially founded. Warden decided to build a fort for protection, and around the fort his staff of 70 men and their families established a small village. The original community of Bloemfontein initially consisted only of English speaking people!

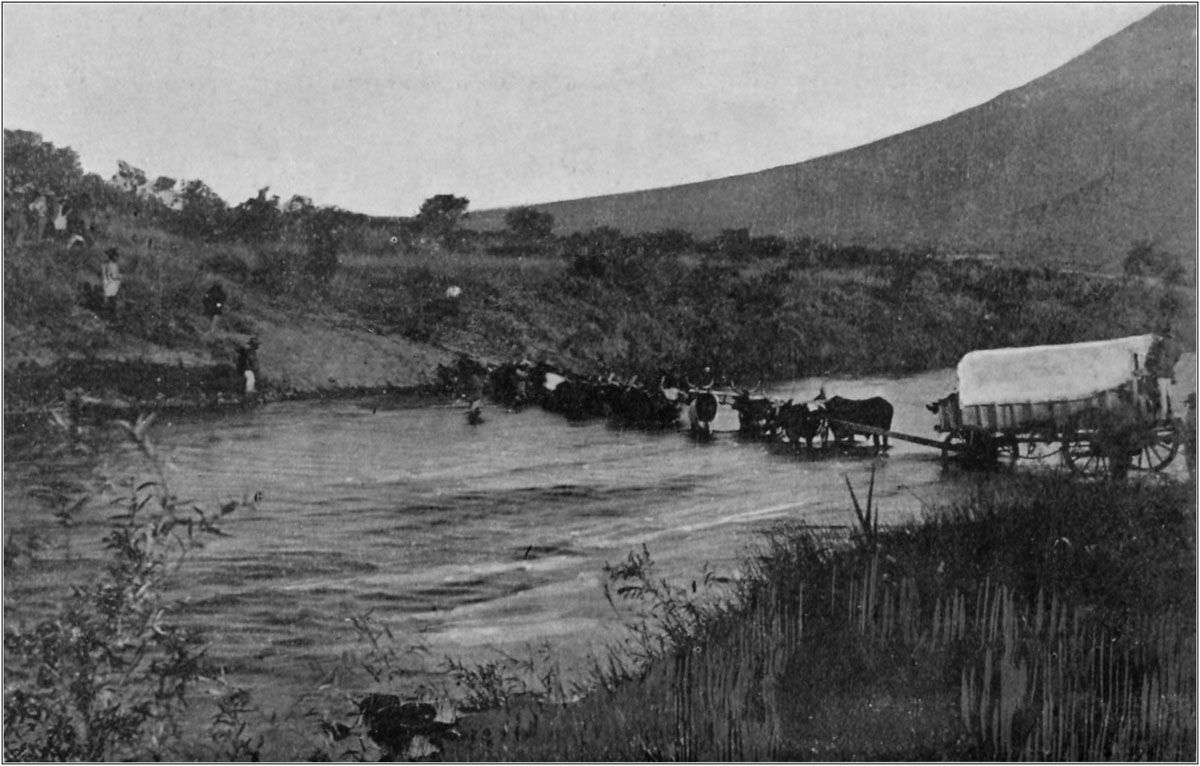

All supplies came by transport riders with ox drawn wagons from the harbours of Port Elizabeth and East London. This made procuring goods, such as building material, clothes, household goods and furniture, difficult and expensive.

On the only hill of any significant height Warden positioned naval cannons to protect the fort and village. This hill, far away from any ocean, became known as Naval Hill! Today it is the site of South Africa’s second largest statue of Nelson Mandela.

Annexation and the Orange River Sovereignity

Relations between the different groups in the area were extremely strained. Ownership of the land between the Caledon and Orange Rivers was the main issue. The new Governor of the British Cape Colony, Sir Harry Smith, decided that the best way to put an end to this problem was to annex the area and set out clear boundaries.

At that time expanding the British Empire was an integral part of the mindset of the English ruling class, who regarded themselves as superior to any other nation or race.

Smith had assured the Boer leader Andries Pretorius that he would not proclaim the land between the Orange and the Vaal rivers as British until the views of the Boers had been consulted. If less than 80 percent of them were in favour of the British action, Smith said he would not proceed with the proclamation.

Without waiting for the result, he annexed the land between the Vaal and Orange Rivers on 3 February 1848. The territory was officially styled the Orange River Sovereignty.

Two battles

The Boers around Winburg were enraged. Pretorius raised a Commando of 1,000 men by June 1848 and chased Henry Warden out of Bloemfontein. British reinforcements led by Sir Harry Smith arrived and fought the Boers at Boomplaats in August 1848. The British were victorious.

Sir Harry Smith then established boundaries. They stretched from the Orange River to the Vaal River. The boundary line in the east –which he named the Warden line — divided territory between British territory and the Basotho. The Caledon River became the boundary line, and the Basotho lost much of the western side of the valley.

King Moshoeshoe was induced to sign the new arrangement in October 1849 although it reduced his fertile land holdings in favour of the Boers.

It was not actually acceptable to Moshoeshoe and he declared war on the British. The British were defeated by Moshoeshoe at the battle of Viervoet in 1851!

The British abandon the Sovereignty

The British government, which had reluctantly agreed to the annexation, now repented its decision. Maintaining the turbulent Sovereignty was too difficult and, with neither harbour nor railway, too expensive to maintain. In addition the Boers wanted independence north of the Orange River and were threatening to side with Moshoeshoe in a war against the British.

The Boers were asked to send delegates to a meeting with the British Special Commissioner Sir George Clerk in August 1853 “for the settling and adjusting of the affairs” of the Sovereignty, and to determine upon a form of self-government.

At that time there were some 15,000 settlers of European origin in the country. Many of them were recent emigrants from the Cape Colony or Britain. The majority vote declared in favour of the retention of British rule!

Chaos followed. Sir George Clerk announced that, as the elected delegates were unwilling to take steps to form an independent government, he would enter into negotiations with other persons.

Following proceedings was a Dr Theal who wrote: “Then was seen forced the strange spectacle of an English commissioner addressing men who wished to be free of British control as the friendly and well-disposed inhabitants, while for those who desired to remain British subjects he had no sympathising word.”

The elected delegates sent two members to England – a long journey then — to try and induce the government to alter their decision.

The minority republican party delegates, led by Josias Hoffman from the Smithfield District, were to decide on a committee to draw up a constitution. Even before this committee met, a royal proclamation had been signed on 30 January 1854 “abandoning and renouncing all dominion” in the Sovereignity.

On 23 February 1854 the Bloemfontein Convention recognising the independence of the country was signed. It would be called the Republic of the Orange Free State. The Bloemfontein Convention made no reference to King Moshoeshoe and did not state what the boundaries between the Basotho kingdom and the OFS were. This was to cause conflict for many years.

The Bloemfontein Convention was signed in the building now known as the Eerste Raadsaal. Major Warden built this typical pioneer building in 1849. The first two presidents of the Republic were sworn in in this building.

Five days later the travelling representatives of the elected delegates had an interview in London with the colonial secretary, the Duke of Newcastle. He informed them that it was now too late to discuss the question of the retention of British rule.

One wonders if this is the one and only time that the British willingly withdrew from land annexed by them and forced independence against the will of the people!

The Republic of the Orange Free State

The 1854 Constitution was largely influenced by the constitutions of the USA and the French Republic. It was regarded as liberal and modern by visiting dignitaries from other countries. Executive authority was entrusted to a President elected by the burghers from a list submitted by the Legislative Assembly, the Volksraad.

At this time the ‘town’ only consisted of simple single-storey houses with face-brick walls and straw roofs, and a few shops that were centred on the market place. With the withdrawal of the British troops, Bloemfontein lost half of its population, and only about 1,000 residents remained.

To the south, the town of Fauresmith was the same size. Both Bloemfontein and Fauresmith were proposed as capital of the Republic. By a narrow margin of votes Bloemfontein was chosen.

The Legislative Counsel of the Republic of the Free State met in the Assembly Hall, which they called the Raadsaal. When they moved to bigger quarters it became known as the Eerste Raadsaal.

The coat of arms of the Orange Free State was the official heraldic symbol of the Orange Free State as a republic from 1857 to 1902, and later, from 1937 to 1994, as a province of South Africa. It is now obsolete. The wavy orange lines represented the Orange River.

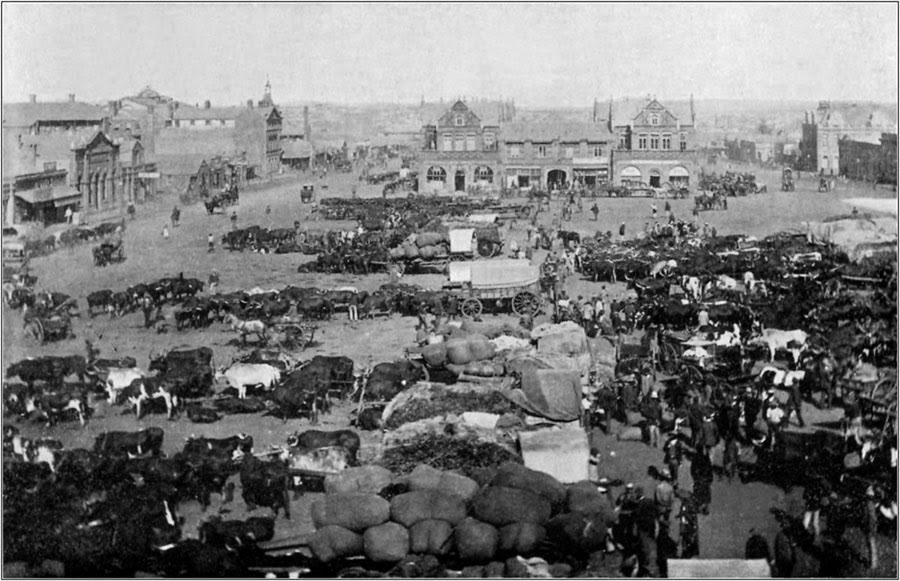

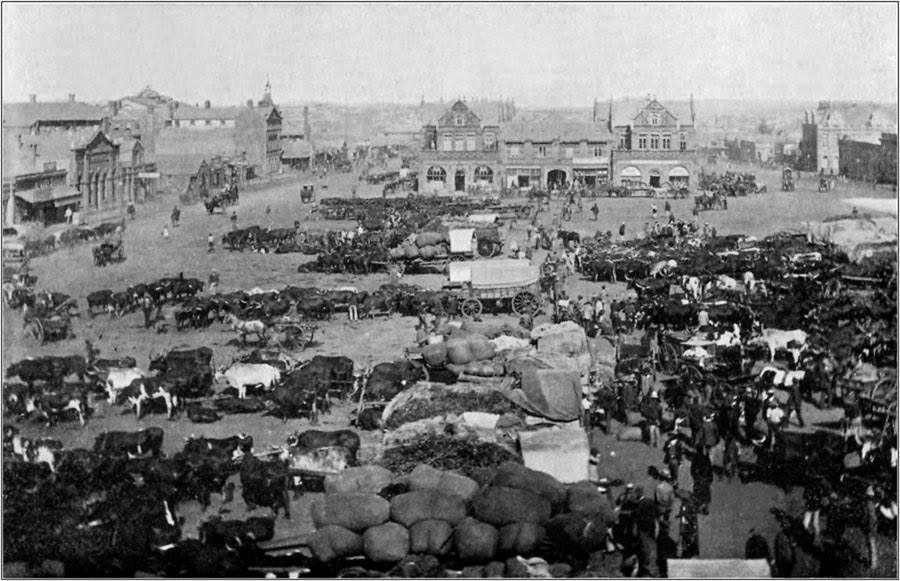

Slowly the population of Bloemfontein grew. Germans, the Dutch, Jews and Afrikaners were the first pioneers to settle in Bloemfontein. Church Square and Market Square (now Hoffman Square) were laid out in 1853. In 1859 a Town Council was needed to manage municipal matters and a market place was established.

Local people in search of work also arrived – people from Bechuana, Hottentots, Fingos, and emancipated slaves. Other groups in the area included the Griqua, the San, the Khoikhoi and Basotho. So soon after its establishment Bloemfontein had thirteen different ‘nationalities’ living there!

Newcomers to the republic were granted full rights of citizenship after six months residence. Many foreigners came to settle in the new republic, and more towns were established.

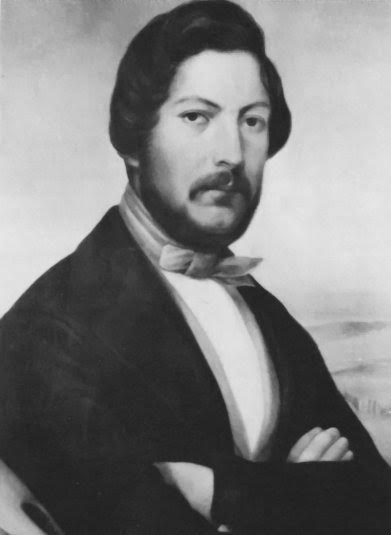

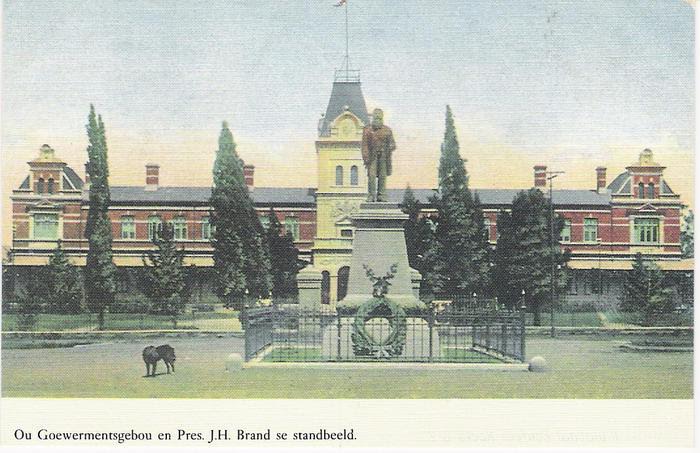

In 1864 Johannes Henricus Brand, who lived in Cape Town, stood for President of the Orange Free State because he greatly admired the constitution. He was not a resident of the Republic and so was not a citizen. And he won! It may well be the only time in history that such an event has occurred.

He was so popular that he was elected for five terms of office. President Brand, who is known to many Afrikaners as ‘die vader van die volk’ or ‘the father of the nation’, died in 1888 while still in office.

The Basotho border: three wars

A major error of the Bloemfontein Convention of 1854 was that it ignored the contentious Warden borderline issue. Disagreement and conflict continued for the next 15 years.

The contested areas were the land between the joining of the Caledon and Orange Rivers, and the area north of the Caledon River, which includes present day Harrismith. Cattle raiding was also a problem. Discussing the matter with Moshoeshoe did not change the situation.

In the 1858 war the Basotho won; they now had guns and were formidable. The Boers suffered substantial losses. They were unable to penetrate the Basotho mountain stronghold of Thaba Bosiu.

Moshoeshoe had realised his precarious position, and had applied for British protection from Governor Philip Wodehouse in the Cape. The Warden Line had then been reaffirmed.

Raids continued. The new president, JH Brand, believed that the OFS should use its military superiority against the Basotho. The Free State army went to war in 1866, seizing cattle and destroying crops.

Moshoeshoe was compelled to accept the peace of Thaba Bosui, due to an exhaustion of Basotho food supplies. He had to cede land to the Free State. He renewed entreaties for British protection.

The Basotho were again slowly advancing over the border line, and further tensions mounted, aggravated by the murders of two Boers.

In July 1867, the third war between the Free State and the Basotho began, and Boer forces overran Moshoeshoe’s land and conquered all the disputed land except the impregnable fortress of Thaba Bosiu.

Annexation of Basutoland

Moshoeshoe, now desperate, accepted the offer of annexation by the British. The remaining Basotho territory became part of the British Empire on 12 March 1868 and was named Basutoland.

In February 1869, the boundaries of Basutoland – nowadays the Kingdom of Lesotho — were drawn up in the Convention of Aliwal-North. This convention gave the conquered territory to the Free State, and the Warden boundary line was extended further south to Langeberg.

The Orange Free State was forced to stop contesting land ownership as war with Basutoland would raise the wrath of Great Britain. At last 50 years of wars over land issues ceased.

King Moshoeshoe had given up his independence in order to achieve a secure future for his people. How many leaders would do that nowadays?

A year later in 1870, King Moshoeshoe, founder of the Basotho nation, died aged 83. All he ever wanted was peace, and diplomatic negotiation rather than war, and yet he spent 50 years of his life in conflicts and wars.

His grave is on the top of Thaba Bosui and Lesotho is now an independent kingdom.

Source: Marduk

Diamond disputes

In the 1860s the whole Free State was economically depressed. When the diamond fields of Jagersfontein and Kimberly were discovered in 1867 and 1870, fortune seekers from all over converged upon Bloemfontein before moving on to the diggings.

This boost in Bloemfontein’s fortunes came just when it was needed. The town became a major service centre for the diamond industry and, for a while, the inland headquarters for a number of major financial and commercial concerns.

However tensions arose with regard to the ownership of the diggings. The diamond fields were near the junction of the Orange and Vaal Rivers, on the western side of the Free State. This was land through which the Griqua regularly moved with their herds. Boundary lines in this area had not been drawn up.

The Griquas, the Orange Free State and the Zuid Afrikaner Republik north of the Vaal River all laid claim to the area. The matter was legally debated for years. Adjudication eventually awarded the land to the Guiquas.

President Brand persuaded the hotheads in the Free State that declaring war on the Griquas would be disastrous as it would inevitably involve the British. A form of resolution eventually came in 1876 when the British Government granted the Orange Free State a large payment in lieu of its territorial claims.

This payment, and the business generated by the mines, enabled several governmental buildings to be constructed in Bloemfontein. Many are now National Monuments.

The Old Municipal Building dates to the 1877. The style is Cape Dutch. A statue of President Brand is at the entrance. It is now the National Afrikaans Literature Museum.

The Dutch Reformed community finally raised the funds to construct a large church which was consecrated in 1880. It had two steeples and soon became known as the ‘twee toring kerk’ — two spire church. It is the only Dutch Reformed Church in South Africa with two steeples. The last three presidents of the Orange Free State took oath of office in this church.

In the early 1880s the Republic’s administration had outstripped the office space available, and it was resolved to build a new Council Chamber – Raadsaal — and governmental buildings, and also a new Presidency.

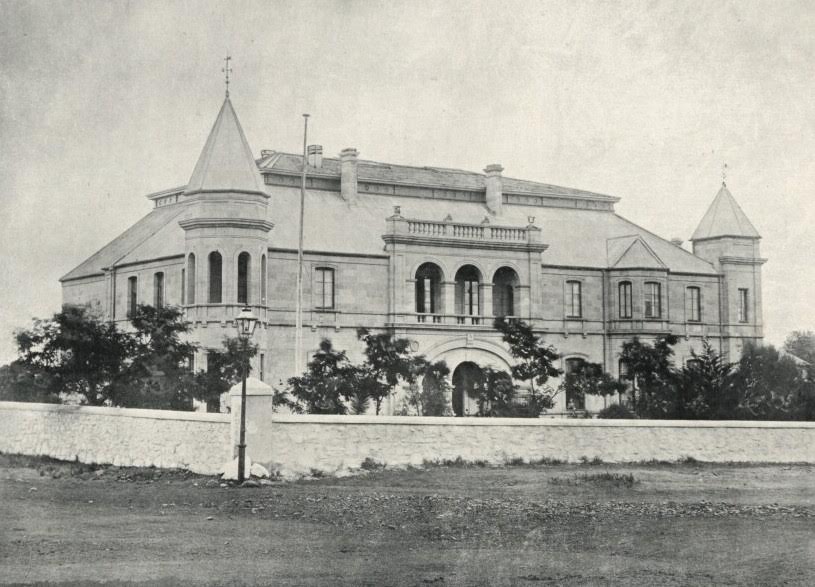

Until now the presidents had been living in the simple abode of Henry Warden with various additions. A competition was held, and the design by Lennox Canning was chosen. It is thought that he derived the style from the manor houses of Scotland.

The Presidency was completed in 1886 and three presidents lived there: Brand, Reitz and Steyn. After Bloemfontein was occupied by the British on 13 March 1900, the building was taken over by Field-Marshal Lord Roberts. Today it is a National Monument.

Various problems delayed completion of the Government Buildings and Raadsaal until 1893. The magnificent building is in the neo-classical style, derived from ancient Roman and Greek structures. The complex is larger than any image can portray, except an aerial one. It is surrounded by lawns, trees and flowerbeds. The ironwork railings around it and the gate were imported from Paris.

Nonetheless the government was not destined to enjoy the comfort and luxury of its new premises for very long. In March 1900 Bloemfontein was occupied by British forces, and the building’s magnificent hall was converted into a military hospital.

After the discovery of gold on the Witwatersrand, the Cape Colony government wanted a railway link to Johannesburg via Bloemfontein. The Orange Free State agreed. Cape Town was already linked to Colesberg, so the new railway went from Colesburg to Bloemfontein.

It opened in 1890 and visitors from all parts of the Colony arrived to attend the opening ceremony. A special medal to commemorate the occasion was struck and distributed to the children of the town.

From Bloemfontein the line continued to Johannesburg. Nine years later the British would use this railway to their advantage during the horrendous Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902.

Today Bloemfontein is the Judicial Capital and Seat of the Supreme Court of Appeal of the Republic of South Africa. South Africa is a member of the British Commonwealth. The boarding schools that were established in the late 1880s to provide education for the children of farmers now have a reputation for excellence. The population has grown from 1,000 to 700,000.

New statues have been commissioned to honour various South Africans. It seems right and fitting that the Judicial Capital of South Africa now honours two great men of peace: Nelson Mandela and King Moshoeshoe.

Written by Beverley Ballard-Tremeer whose grandmother, great grandmother and great grandfather were born in the Orange Free State. The latter was one of President Brand’s personal staff.